International Shipping Costs: Determinants and Outlook

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Short-term fluctuations in the demand for and the supply of global shipping services are key determinants of international shipping costs.

- An increase in shipping demand and a rise in shipping prices during the COVID-19 pandemic led to higher containership earnings and more orders for new vessels.

- As containerships ordered throughout the pandemic are delivered, excess demand for global shipping services should recede, further easing pressure on shipping prices.

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, the global economy experienced widespread supply chain disruptions and an unprecedented rise in international shipping costs. These developments have limited access to internationally traded goods while contributing to higher inflation.See Maggie Isaacson and Hannah Rubinton’s 2022 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working paper, “Shipping Prices and Import Price Inflation,” for more about the impact of shipping costs on inflation, and see Ana Maria Santacreu and Jesse LaBelle’s 2022 Review article, “Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” for more about the impact of supply chain disruptions on inflation.

In this article, we investigate the determinants of international shipping costs. First, we explain how proxies of demand and supply account for shipping cost dynamics. Then, we use forecasts of these factors to evaluate the likely path of international shipping costs over the next few years.

Analytical Framework

In our analysis of international shipping costs, we considered global shipping demand to be decreasing with higher shipping costs, because households and firms are likely to reduce the amount they demand when prices rise. On the other hand, we considered global shipping supply to be increasing with higher shipping costs, because shippers are likely to enlarge shipping capacity if prices are higher.

Critically, the steepness of the supply curve depends on the time horizon; it might not be possible for shipping supply to increase much in the short term because building new ships takes time. We interpreted observed shipping costs as the equilibrium price that equates global demand with global supply. The implication is that fluctuations in either demand or supply will change equilibrium shipping costs.

Historical Dynamics of International Shipping Costs

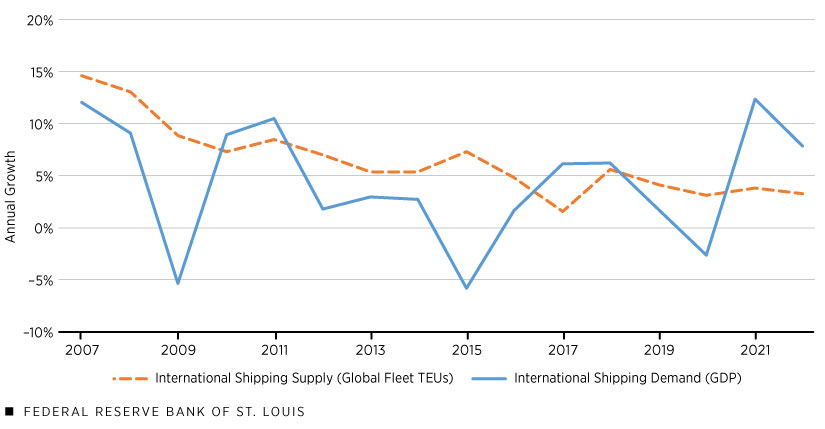

We examined the recent dynamics of international shipping demand and supply from the lens of this framework. As a proxy for shipping demand over time, we used cross-country gross domestic product (GDP) data from the World Economic Outlook, which is published by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).Data in the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database are collected at the country level. To produce an aggregated GDP estimate, we calculated the sum of nominal GDP (in U.S. dollars) in each year from 2007 to 2022 for all countries with data over the entire period. We focused on “global” GDP as our proxy for demand because it is likely to capture fluctuations in economic activity and aggregate demand for goods, while being less affected by changes in international shipping costs than a more direct measure of shipping demand, such as aggregate imports, would be.Our findings were robust to using aggregate imports as our proxy for demand. We proxied international shipping supply using data from Clarksons Research on the size of the global containership fleet (measured in 20-foot equivalent units, or TEUs).Specifically, data are from the Clarksons Research Shipping Intelligence Network.

The following figure plots the year-to-year growth rate of these proxies for shipping demand and supply for the period from 2007 through the second quarter of 2022. The demand for shipping services (i.e., GDP) is significantly more volatile than international shipping supply (i.e., the amount of containership capacity). The figure shows periods in which the demand for shipping has grown significantly faster than shipping supply, as well as periods in which they have both grown at similar rates.

Global Shipping Demand and Supply, 2007-2022

SOURCES: IMF, Clarksons Research and authors’ calculations.

The next figure plots (1) the difference between the growth rates of these shipping demand and supply determinants, which we refer to as shipping excess demand, and (2) international shipping costs. We measured the latter using data on global containership spot rates.Global containership spot rates are from Drewry’s World Container Index, which expresses shipping prices in U.S. dollars per 40-foot container. Periods in which demand for shipping grew faster than supply (an increase in shipping excess demand) are generally associated with shipping cost increases. And indeed, the figure shows that these series track each other closely, with a correlation of 0.65. To the extent that the global fleet is near full utilization, shippers ration short-run excess demand by raising prices.

Global Shipping Excess Demand and Shipping Prices, 2007-2022

SOURCES: IMF, Clarksons Research, Drewry and authors’ calculations.

Global Shipping throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic

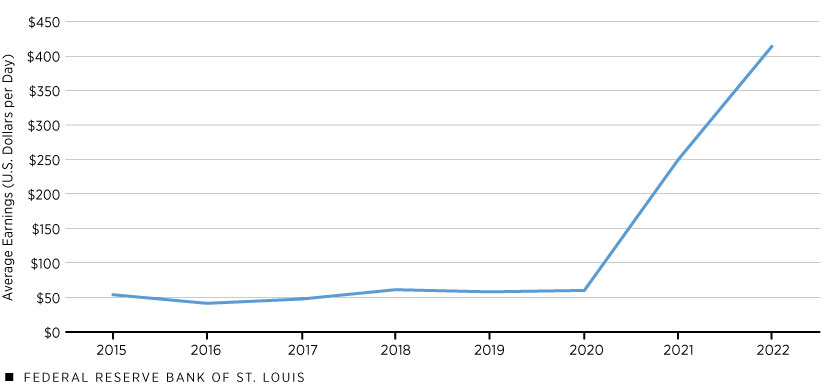

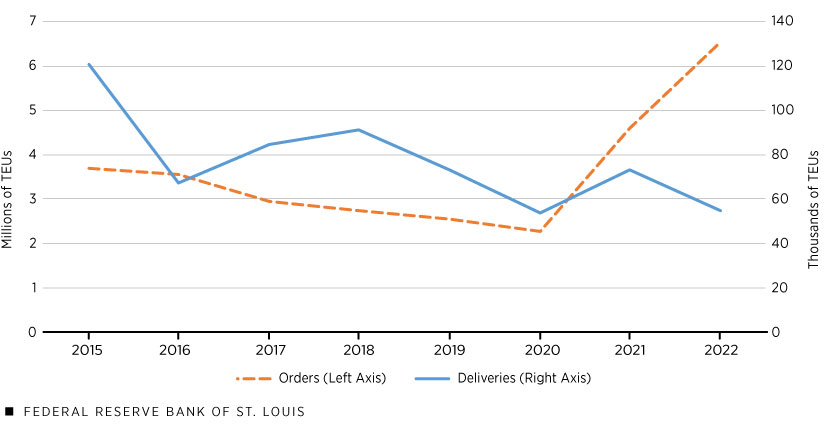

As illustrated in the preceding figure, shipping demand outstripped supply following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, substantially raising international shipping prices. The following two figures examine the implications of these developments for the international shipping industry.All series in these two figures are from the Clarksons Research Shipping Intelligence Network.

The first figure below shows that containership earnings increased astronomically over this period.The series Average Containership Earnings from Clarksons Research records average charter rates over a range of containership sizes. It captures the “theoretical earnings level” of these ships and is reported monthly. The series used month-end assessments through 2018, after which it switched to the monthly average of weekly assessments. Given these larger returns to owning containerships, global shippers increased their orders for such vessels, as observed in the second figure below. An increase of international shipping capacity should eventually increase shipping supply, decrease shipping excess demand and lower shipping prices. But this process is likely to take time, because while shippers have already placed new orders for containerships, many of these new ships have yet to be actually delivered to the fleet (as the second figure below also demonstrates).

Global Containership Earnings, 2015-2022

Global Containership Orders and Deliveries, 2015-2022

SOURCES FOR THE TWO FIGURES: Clarksons Research and authors’ calculations.

The Future of the Shipping Industry

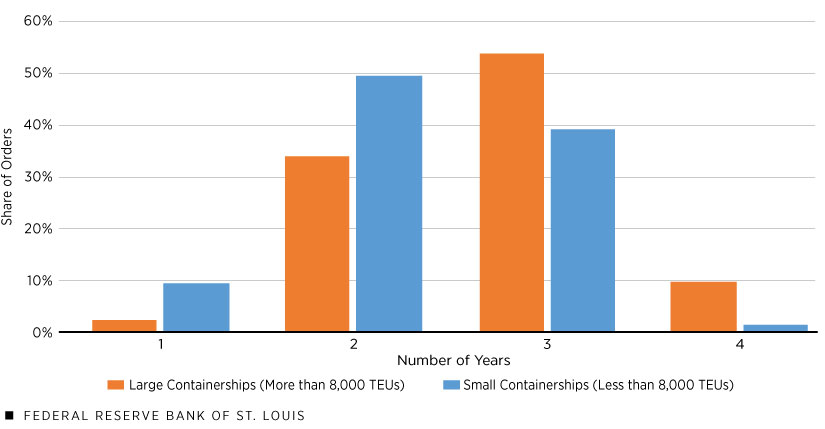

This naturally begs the question: When should we expect to see these containerships delivered and added to the global fleet? To answer, we turned to the Clarksons Research containership orderbook, a data set that contains information on all containerships currently on order, including their size, order date and expected delivery date. These data afford us a better understanding of the estimated time between containership orders and deliveries. The following figure shows that this construction lag is about two to four years for both large and small containerships, with somewhat longer times for larger ships.

Time to Complete Containerships Currently under Construction

SOURCES: Clarksons Research and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: A small fraction of containerships were expected to take less than one year or five or more years to build.

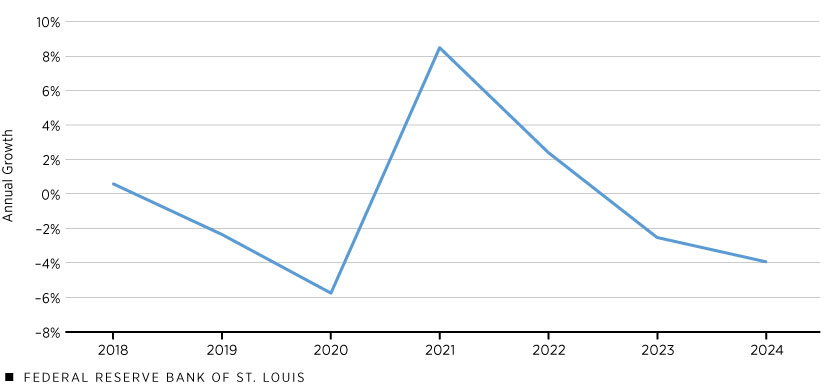

What is the implication of the containership construction lag for expected international shipping prices in the coming years? Answering this question requires us to forecast future excess demand for shipping. We constructed such a forecast by combining the expected growth in international shipping supply given current containership orders and expected delivery dates with cross-country GDP forecasts from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook. The figure below plots shipping excess demand dynamics for the period from 2018 through 2024, with data points for 2023 and 2024 based on our forecast.

Actual and Forecasted Global Shipping Excess Demand, 2018-2024

SOURCES: IMF, Clarksons Research and authors’ calculations.

Our estimates indicate that excess demand for shipping in 2023 should revert to the pre-pandemic levels observed in 2019, decreasing even further in 2024. While these patterns suggest the likely trend for international shipping prices in coming years, they do not necessarily imply that international shipping prices will fully return to pre-pandemic levels.

For instance, the massive COVID-19-related price shock may have reconfigured the global network of shipping services, as well as firms’ supply chain practices, in a way that alters observed equilibrium prices even after excess demand falls back to pre-pandemic values.

The Outlook for International Shipping Costs

Understanding the dynamics of international shipping supply, and the lags involved in the production of new containerships, is critical for understanding the forces that shape international shipping costs. As the significant number of containerships ordered throughout the COVID-19 pandemic is delivered, excess demand for shipping is likely to recede, easing pressures on international shipping costs.

Notes

- See Maggie Isaacson and Hannah Rubinton’s 2022 Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis working paper, “Shipping Prices and Import Price Inflation,” for more about the impact of shipping costs on inflation, and see Ana Maria Santacreu and Jesse LaBelle’s 2022 Review article, “Global Supply Chain Disruptions and Inflation during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” for more about the impact of supply chain disruptions on inflation.

- Data in the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database are collected at the country level. To produce an aggregated GDP estimate, we calculated the sum of nominal GDP (in U.S. dollars) in each year from 2007 to 2022 for all countries with data over the entire period.

- Our findings were robust to using aggregate imports as our proxy for demand.

- Specifically, data are from the Clarksons Research Shipping Intelligence Network.

- Global containership spot rates are from Drewry’s World Container Index, which expresses shipping prices in U.S. dollars per 40-foot container.

- All series in these two figures are from the Clarksons Research Shipping Intelligence Network.

- The series Average Containership Earnings from Clarksons Research records average charter rates over a range of containership sizes. It captures the “theoretical earnings level” of these ships and is reported monthly. The series used month-end assessments through 2018, after which it switched to the monthly average of weekly assessments.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us