Immigrant Employment Patterns during the Pandemic

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- During the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, immigrants—a large and vital part of the U.S. workforce—suffered a disproportionate loss in employment.

- The share of immigrants in total U.S. employment, in the overall U.S. labor force and in certain occupational groups fell sharply during the early part of the pandemic.

- In recent months, the U.S. labor market appears to be recovering to its pre-pandemic patterns of immigrant employment.

Immigrants are a vital part of the U.S. workforce, constituting almost one-fifth of the U.S. labor force in December 2021. While the effect of pandemic-related disruptions on overall U.S. employment has been widely discussed, their effect on immigrant employment has not received corresponding attention.

A July 2021 Pew Research Center article noted that the pandemic disproportionately raised unemployment among foreign-born workers.See Rakesh Kochhar and Jesse Bennett’s “Immigrants in U.S. experienced higher unemployment in the pandemic but have closed the gap,” Pew Research Center, July 26, 2021. The unemployment rate for foreign-born workers climbed from about 4% in the first quarter of 2019 to a peak of 15.3% by the second quarter of 2020. In comparison, the unemployment rate for U.S.-born workers rose from 4.1% to 12.4% over the same period. The article also found that employment among immigrants recovered well: The unemployment rate fell to 5.9% by the second quarter of 2021, which was just 0.1 percentage points higher than the rate for native workers.

Unlike native workers, who can stay in the U.S. when faced with job losses due to COVID-19 disruptions, some unemployed immigrants may return to their home nations, especially if their U.S. visas are employment-based. This tends to drive down both the number of foreign-born unemployed workers looking for jobs in the U.S. and the total foreign-born labor force. Because the immigrant unemployment rate is the proportion of the immigrant labor force that is unemployed and looking for work, the exit of some foreign-born workers must reduce the rate.Say, for example, there were 5,000 unemployed immigrant workers out of a foreign-born labor force of 50,000 workers, which translates to an immigrant unemployment rate of 10%. If 1,000 of those unemployed immigrant workers left the U.S. labor force, the rate would decline to 8.2%.

In turn, this suggests the 15.3% unemployment rate cited in the Pew report is probably lower than what the foreign-born unemployment rate would have been in the absence of any foreign-born workers leaving the U.S. Related to this point, we explore whether COVID-19-related disruptions led to substantial job losses among foreign-born workers and drove some of them to return to their home nations. We accomplish this using monthly data to compare pre- and post-pandemic immigrant employment and labor force patterns during the period from January 2018 to December 2021.Current Population Survey microdata, accessed via IPUMS CPS. See IPUMS.

This article makes two contributions. First, we consider how the pandemic has affected the share of immigrants in the U.S. population, the share of immigrant employment in total U.S. employment, and the share of foreign-born workers in the U.S. labor force. Second, we focus on how the pandemic has affected the share of immigrant employment in the top six immigrant-intensive occupational groups at the end of 2019 (i.e., those with the highest immigrant shares in employment during December 2019).

Immigration and Immigrant Employment

Immigration policy and other factors—including push factors, like poverty or political instability in immigrants’ source nations, and pull factors, like good job opportunities in the U.S.—affect immigration flows. Immigration flows, in turn, determine how the size of the foreign-born population in the U.S. evolves over time.

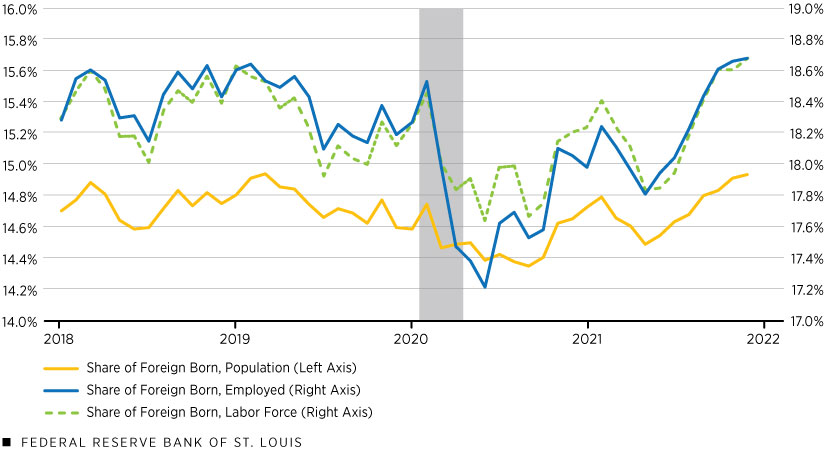

The figure below shows that the pandemic and associated disruptions initially sharply reduced the foreign-born share of the U.S. population, with it reaching a trough in September 2020. This implies a net decline in immigration during this period. Since then, there has been a sharp recovery, with the December 2021 share exceeding the pre-pandemic share.

Share of Foreign Born in Total Population, Employed Population and U.S. Labor Force

SOURCES: Current Population Survey microdata accessed via IPUMS CPS and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Shares of foreign-born workers in the U.S. labor force and employed population are reflected in the secondary y-axis on the right. The shaded area represents the COVID-19 recession, which lasted for a period of two months beginning in February 2020 and ending in April 2020.

At the same time, the share of employed immigrants in total U.S. employment also fell sharply, from about 18.5% in February 2020 to 17.2% in June 2020. Although total U.S. employment fell sharply as well during this period, the impact on immigrant employment was proportionally higher. The fall in immigrant employment also coincides with the decline in immigration during the pandemic. As pandemic-related disruptions eased, immigrants’ employment share recovered to about 18.7% by December 2021.

The share of immigrants in the U.S. labor force was about 18.5% at the beginning of the COVID-19 recession in February 2020. Although the recession ended in April 2020, immigrants’ share in the labor force reached a trough of about 17.6% in June 2020 but then recovered to 18.7% in December 2021. The temporary declines in the shares of immigrants in the U.S. population, immigrant employment and the immigrant labor force all point to the fact that COVID-19 posed a heavy but temporary burden on both actual and potential immigrants during this period.

The Top 6 Occupational Groups Ranked by Immigrant Employment Shares

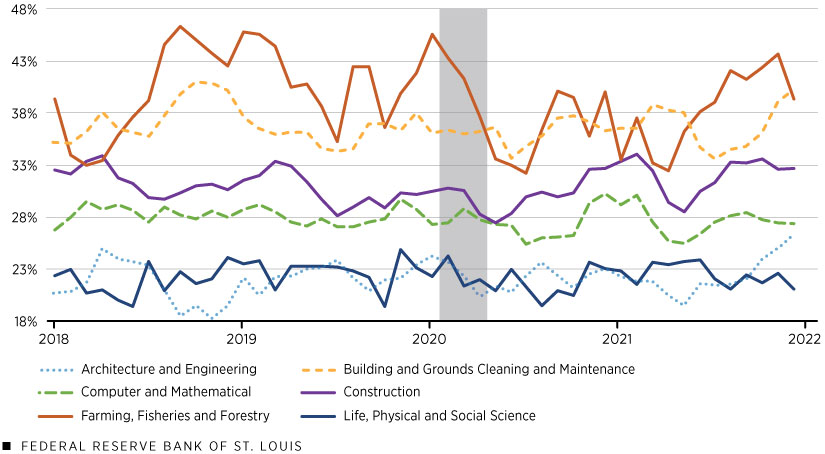

Pandemic-related disruptions had disparate effects on immigrant employment shares across occupational groups, as some were hurt much more than others. The next figure shows that the share of foreign-born workers in the farming, fisheries and forestry occupational group fell precipitously from almost half to about one-third by July 2020. Although seasonal factors can be important in the farming sector, the July 2020 number is the lowest among all the July numbers for the period from 2018 through 2021.

Top 6 Shares of Foreign Born (in December 2019) by Occupational Group over Time

SOURCES: Current Population Survey microdata accessed via IPUMS CPS and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: The shaded area represents the COVID-19 recession, which lasted for a period of two months beginning in February 2020 and ending in April 2020.

However, another top occupational group, building and grounds cleaning and maintenance, exhibits almost a flat line in the recessionary period and a modest dip shortly after the recession. Although further data and analysis are needed to be sure, it is possible that border disruptions reduced the availability of migrant labor in the farming, fisheries and forestry occupational group, contributing to the sharp decline in the foreign-born employment share during the recessionary period.

Recovery in immigrant shares has been uneven among the different occupational groups, with the top three groups showing markedly higher shares in December 2021 compared with their respective pandemic-era lows.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily disrupted immigration and immigrant employment patterns in the U.S. During the worst of the pandemic in the early part of 2020, immigrants suffered a disproportionate loss in employment. Both lower immigrant employment in the U.S. and pandemic-related disruptions that resulted in fewer potential immigrants to the U.S. probably contributed to this outcome. However, immigrant employment has strongly recovered, and in recent months, the U.S. labor market seems to be returning to pre-pandemic patterns of immigrant employment.

Endnotes

- See Rakesh Kochhar and Jesse Bennett’s “Immigrants in U.S. experienced higher unemployment in the pandemic but have closed the gap,” Pew Research Center, July 26, 2021.

- Say, for example, there were 5,000 unemployed immigrant workers out of a foreign-born labor force of 50,000 workers, which translates to an immigrant unemployment rate of 10%. If 1,000 of those unemployed immigrant workers left the U.S. labor force, the rate would decline to 8.2%.

- Current Population Survey microdata, accessed via IPUMS CPS. See IPUMS.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us