GDP Decline, Inflation Heighten Uncertainty in U.S. Economic Outlook

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Real GDP fell unexpectedly by 1.4% in the first quarter of 2022, after a nearly 7% gain the prior quarter, leading forecasters to lower growth projections for 2022 and 2023.

- Inflation, which hit a 40-year high in March 2022 and remains well above the FOMC’s 2% target, appears to be the biggest headwind currently facing the U.S. economy.

- Demand for goods, services and labor strengthened through the first four months of 2022, with unemployment returning to near its 50-year low of 3.5%.

U.S. and global economic and financial conditions weakened over the past three months. This weakness reflects many factors, including the Russia-Ukraine war and a surge in U.S. inflation that has triggered expectations of further aggressive action by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to increase its target range for the federal funds rate and reduce the size of its balance sheet. Still, the demand for labor and for goods and services in the U.S. remained solid through the first four months of 2022, despite reductions in real household purchasing power due to unexpectedly high inflation. The highly uncertain nature of the economic outlook has led many forecasters to mark down their projections for U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2022 and 2023 to a rate closer to trend growth (roughly 2%).Trend real GDP growth is a long-run concept. At a high level, it is the sum of the growth rate of the economy’s labor productivity (output per hour) and the growth rate of the labor force that would be expected to prevail when the economy’s resources are operating at their normal capacity. Forecasts earlier in the year had called for real GDP to grow at a pace well above this rate.

An Unexpected Decline in GDP

Real GDP declined in the first quarter of 2022 at an annual rate of 1.4%, following a gain of nearly 7% in the previous quarter. A decline in real GDP is usually viewed ominously, as it may signal weakness that often occurs before a recession. However, declines in real GDP during business expansions have occurred before, and often because of one-off developments, such as severe weather. The decline in the first quarter was due largely to sizable decreases in real net exports and the rate of real nonfarm inventory investment that, together, subtracted 4 percentage points from real GDP growth. On a brighter note, personal consumption expenditures and nonresidential (business) and residential fixed investment combined to account for a little more than 3 percentage points of real growth. Thus, demand for real goods and services remained healthy, as final sales to private domestic purchasers rose 2.6% in the first quarter—nearly 1 percentage point higher than the previous quarter’s increase.Final sales to private domestic purchasers is the sum of personal consumption expenditures and gross private fixed investment. See this Bureau of Economic Analysis glossary.

Headwinds, Tailwinds and Whirlwinds

The strengthening demand for goods and services was impressive, given that several headwinds buffeted the U.S. economy in 2022’s first quarter. These included:

- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent imposition of widespread sanctions against Russia by Western countries that led to sharp increases in energy and non-energy commodity prices

- A resurgence of COVID-19 cases in China that prompted severe lockdowns in several major cities and the closure of many manufacturing facilities and ports

- An omicron-variant surge in the U.S. that pushed daily COVID-19 case rates (per million) to a record high in January, spurring some consumers to postpone travel and other leisure and entertainment activities

- Monetary policymakers raising the policy interest rate and telegraphing several additional rate hikes in 2022. These actions triggered sharp increases in long-term interest rates (including mortgage rates), strengthened the dollar and lowered stock prices.

In addition, firms and consumers continued to grapple with shortages of key manufactured inputs (such as semiconductors), ongoing bottlenecks in the production and distribution of goods, rising cost pressures and an inability to fill many job openings—particularly those in the leisure and hospitality industries.

Prices Under Pressure

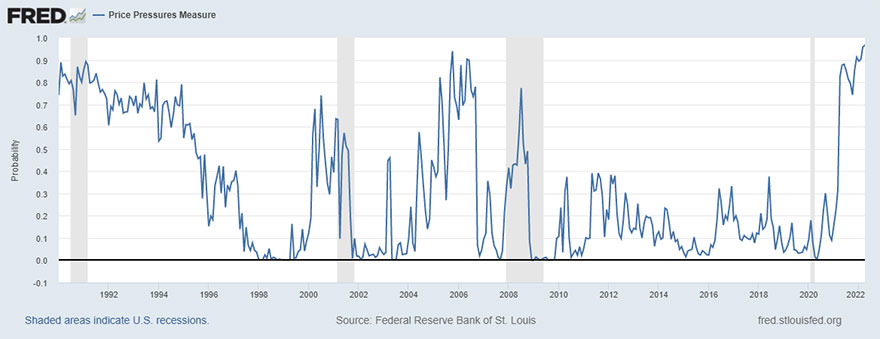

NOTES: The series presented in this figure measures the probability that the expected personal consumption expenditures price index (PCEPI) inflation rate (12-month percent changes) over the next 12 months will exceed 2.5%.

Perhaps the biggest headwind facing the U.S. economy over the past year or so has been the exceptionally high rate of consumer price inflation, which hit a 40-year high in March 2022. Inflation is a tax on household cash balances. Moreover, if household nominal incomes do not increase as fast as inflation, then households’ real standard of living declines. This is called a loss in purchasing power. In the first quarter of 2022, the employment cost index for private workers—the most comprehensive measure of labor compensation (wages, salaries and benefits)—was up 4.75% from four quarters earlier; this was the largest increase in more than 31 years. However, the personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, rose even more in the first quarter, to 6.3%, from a year earlier. Thus, in real terms, labor compensation fell by about 1.5 percentage points in the first quarter from a year ago. In fact, real labor compensation has declined for four straight quarters. Unless reversed, declines in real compensation pose a threat to consumer spending, the largest component of real GDP. Hearteningly, though, real retail sales—and industrial production—rose by more than expected in April.

The economy has continued to benefit from several tailwinds, including strong demand for labor that drove the unemployment rate back down to 3.6% in April 2022, near the 50-year low of 3.5% that it registered in January and February 2020. Business capital spending remained solid, helped by robust profit margins. In fact, some firms have increased their outlays on labor-saving capital goods in response to rising labor costs and an inability to fill open job positions. Housing also remained a source of strength for the economy, benefiting sellers, lenders and homebuilders and spurring double-digit percentage gains in house prices. Indeed, rising house prices have helped to offset some of the loss in wealth stemming from this year’s sharp drop in stock prices. However, history suggests that rising mortgage rates will eventually cool the housing and mortgage markets.

Seeing Through the Glass Darkly

The outlook for the economy in 2022 and 2023 has dimmed appreciably over the past six months. Although some economic analysts predict a recession sometime in the next 12 to 18 months, the May Survey of Professional Forecasters from the Philadelphia Fed forecasts that real GDP will increase by 2.5% in 2022 and 2.3% in 2023. The unemployment rate is forecast to average 3.6% in each year. In short, it’s difficult to have a recession with strong labor demand. That said, high levels of uncertainty often lead households and firms to delay or cancel expenditures, which can result in lower growth. Thus, risks to GDP growth now tilt to the downside. From an inflation standpoint, cost pressures (labor and nonlabor costs) remain intense for most firms—and many have encountered little difficulty in passing on these higher costs to consumers. Accordingly, the longer inflation stays well above the Fed’s 2% target, the more likely it is that the FOMC will need to raise its policy rate by more than what markets expect.

Devin Werner, a senior research associate at the Bank, provided research assistance.

Endnotes

- Trend real GDP growth is a long-run concept. At a high level, it is the sum of the growth rate of the economy’s labor productivity (output per hour) and the growth rate of the labor force that would be expected to prevail when the economy’s resources are operating at their normal capacity.

- Final sales to private domestic purchasers is the sum of personal consumption expenditures and gross private fixed investment. See this Bureau of Economic Analysis glossary.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us