On-Time Mortgage Payments Recover, Even in Financially Distressed Areas

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- By early 2022, the share of mortgage borrowers paying on time had returned to pre-COVID-19 recession levels in areas of both high and low financial distress.

- Remarkably, the percentage of households that were current on their mortgage payments recovered faster and further in areas of high financial distress.

- This broad recovery suggests that a sharp rise in foreclosure rates is unlikely as pandemic-related mortgage forbearance programs come to an end.

The U.S. economy entered the COVID-19 recession in February 2020 and by April, with the pandemic officially underway, unemployment was at a record 14.7%. This article examines the pandemic’s impact on mortgages by assessing how repayment rates—that is, the percentage of mortgage borrowers paying on time—varied between two areas with different levels of pre-pandemic financial distress and the possible implication this may have for foreclosure rates.In our June 2021 Regional Economist article, “Foreclosure Rate Drops during COVID-19 despite Dip in On-Time Mortgage Payments,” we examined the differences between mortgage nonpayment and foreclosure rates in the 2020 COVID-19 recession compared with the 2008-09 recession.

A prior analysis separated U.S. ZIP codes into quintiles based on the portion of households that were at least 30 days delinquent on credit card payments at some point in 2018.See the working paper “Financial Distress and Macroeconomic Risks (PDF),” co-authored by Kartik Athreya, Ryan Mather, José Mustre-del-Río and Juan M. Sánchez. The following table shows quintile-level averages for this measure of financial distress, as well as quintile-level averages for income, median home value, mortgage debt and credit line usage for 2018.

| Quintile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |

| Share of households that were 30 days or more late on credit card debt | 7.4% | 10.4% | 12.6% | 14.9% | 18.6% |

| Adjusted gross income per capita | $77,277 | $48,373 | $39,819 | $34,772 | $27,746 |

| Median home value | $554,501 | $358,534 | $295,048 | $266,940 | $221,784 |

| Average mortgage debt | $125,647 | $85,422 | $67,484 | $55,851 | $42,701 |

| Share of homeowners that used 80% of credit limit or more | 3.2% | 4.9% | 6.6% | 8.3% | 11.3% |

| SOURCES: FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, IRS, U.S. Census, Zillow and authors’ calculations. | |||||

| NOTE: Averages are weighted by number of households in each ZIP code. | |||||

In the least financially distressed quintile (the first quintile), an average of 7.4% of households were 30 days or more late on their credit card payments. The most financially distressed quintile (the fifth quintile) averaged 18.6%. Further, the least financially distressed quintile had nearly three times the income, more than double the median home value, and almost triple the mortgage debt as the most financially distressed quintile.

Notably, the least financially distressed quintile had fewer homeowners using over 80% of their credit limit than the most financially distressed quintile. On average, 3.2% of homeowners in the least financially distressed quintile used more than 80% of their credit limit versus 11.3% of homeowners in the most financially distressed quintile. This last indicator is crucial to understanding pre-pandemic differences among homeowners across quintiles in access to credit to respond to potential shocks.

The second, third and fourth quintiles had values between those of the first and fifth. Therefore, in the remainder of the article, we simplify the analysis by focusing only on the first and fifth quintiles of financial distress.

The Fall and Rise of Mortgage Repayment Rates

To determine how mortgage repayments evolved during the pandemic in regions with different pre-pandemic levels of financial distress, we combined a random sample of loan-level data from Black Knight McDash with the first and fifth quintiles of financial distress described above. Each month, Black Knight McDash reports a loan’s status as current (that is, payments were on time), delinquent, in foreclosure or other.The dataset contains approximately 99,000 loans per month for the quintile of least financial distress (Q1) and approximately 91,000 loans per month for the quintile of highest financial distress (Q5). Note that since the CARES Act established generous forbearance programs for 2020 and 2021, noncurrent loans in our sample are not necessarily on the path to foreclosure. Borrowers with loans in forbearance do not make payments and can avoid foreclosure by resuming payments, or becoming current, by the end of the forbearance program.

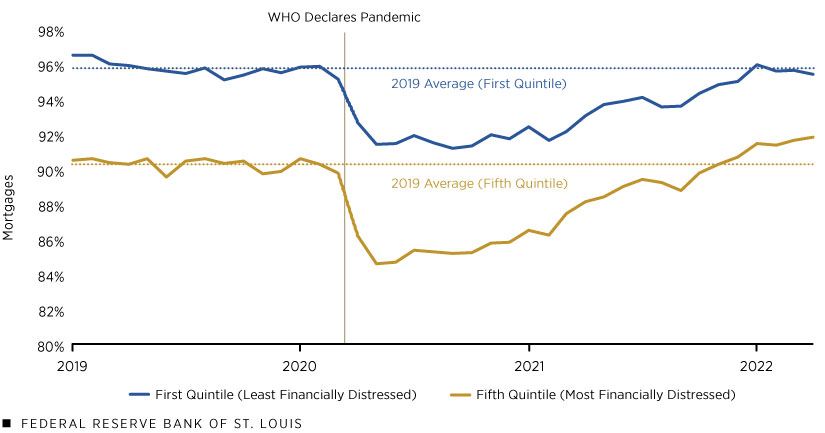

The following figure shows the percentage of mortgages reported as “current” from January 2019 to April 2022 for households in the least financially distressed first quintile (Q1) and the most financially distressed fifth quintile (Q5). For both groups, a high percentage of loans are current, that is, not in delinquency or foreclosure. Predictably, the Q1 line is always above the Q5 line. In other words, households in low-distress ZIP codes are more likely to be current on their mortgages than households in high-distress ZIP codes. The horizontal dotted lines indicate the average percentage of current loans in 2019, the last full year before the pandemic, for each group.

Mortgages Current on Payments over Time by Quintile of Financial Distress

SOURCES: FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax, Black Knight McDash and authors’ calculations.

NOTE: The vertical gray bar marks March 11, 2020, the date that the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

The vertical gray bar marks March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Approximately at this date, the percentage of mortgages that were current declined for both quintiles. By May 2020, the percentage of current loans in the least distressed quintile had fallen significantly to 91.53%, a 4.4 percentage point decline relative to its 2019 average of 95.93%. At the same time, the percentage of current loans in the most distressed quintile had dropped to 84.64%, a 5.74 percentage point decline relative to its 2019 average of 90.38%.

Labor income worsened for both groups during this period, but it declined much more for the fifth quintile than for the first quintile. From April 2020 to December 2020, 14.4% of people in first-quintile ZIP codes and 21.7% of people in fifth-quintile ZIP codes reported labor income losses greater than 50%.See Table 5 in the previously mentioned working paper, “Financial Distress and Macroeconomic Risks (PDF),” from Kartik Athreya, Ryan Mather, José Mustre-del-Río and Juan M. Sánchez.

Perhaps more remarkable is that, as the figure above also shows, the rate of mortgages that were current recovered for both groups over the year and a half following May 2020. While mortgage repayment in the fifth-quintile ZIP codes recovered faster than in the first-quintile ZIP codes, the rate of current loans returned to the 2019 average in both quintiles. And while the rate of current loans to first-quintile households had risen just slightly above the 2019 average by January 2022, the fifth quintile reached its 2019 average sooner, in November 2021. As of April 2022, the repayment rate in the fifth quintile, where households were the most financially distressed pre-pandemic, was 1.57 percentage points above the 2019 average.

What Does This Mean for Future Foreclosure Rates?

As pandemic-induced mortgage forbearance programs end in the following months, some uncertainty about the future behavior of foreclosure rates is reasonable.The CARES Act forbearance program officially began in April 2020 and borrowers could enroll through September 2021. Since borrowers could request up to a year of forbearance, the last wave of forbearance will end in September 2022. Borrowers with certain loans could enroll for up to 18 months if the initial forbearance began prior to Feb. 28, 2021, or June 30, 2020, depending on the federal backing of the loan. See the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau for more details. Even so, the recovery of mortgage repayment rates suggests that it is unlikely mortgage foreclosure rates will increase sharply due to the end of forbearance programs.

Endnotes

- In our June 2021 Regional Economist article, “Foreclosure Rate Drops during COVID-19 despite Dip in On-Time Mortgage Payments,” we examined the differences between mortgage nonpayment and foreclosure rates in the 2020 COVID-19 recession compared with the 2008-09 recession.

- See the working paper “Financial Distress and Macroeconomic Risks (PDF),” co-authored by Kartik Athreya, Ryan Mather, José Mustre-del-Río and Juan M. Sánchez.

- The dataset contains approximately 99,000 loans per month for the quintile of least financial distress (Q1) and approximately 91,000 loans per month for the quintile of highest financial distress (Q5). Note that since the CARES Act established generous forbearance programs for 2020 and 2021, noncurrent loans in our sample are not necessarily on the path to foreclosure. Borrowers with loans in forbearance do not make payments and can avoid foreclosure by resuming payments, or becoming current, by the end of the forbearance program.

- See Table 5 in the previously mentioned working paper, “Financial Distress and Macroeconomic Risks (PDF),” from Kartik Athreya, Ryan Mather, José Mustre-del-Río and Juan M. Sánchez.

- The CARES Act forbearance program officially began in April 2020 and borrowers could enroll through September 2021. Since borrowers could request up to a year of forbearance, the last wave of forbearance will end in September 2022. Borrowers with certain loans could enroll for up to 18 months if the initial forbearance began prior to Feb. 28, 2021, or June 30, 2020, depending on the federal backing of the loan. See the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau for more details.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us