Getting Ahead of U.S. Inflation: A Lesson from 1974 and 1983

The Federal Reserve has a mandate to promote stable prices for the U.S. economy as well as maximum employment. Consistent with the price stability part of that mandate, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has set an inflation target of 2%, as measured by the year-over-year percentage change in the price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE).

Inflation in the U.S. is currently running far above the Fed’s 2% target and is at levels last seen in the 1970s and early 1980s. The FOMC faced inflation levels in 1974 and 1983 that were similar to today’s inflation rate, but its policy responses were very different in the two episodes. Consequently, the results were also quite different. The contrast between the 1974 and 1983 experiences has convinced many that it is important to “get ahead” of inflation—a lesson that is valuable today.

There are multiple demand and supply factors contributing to today’s high inflation, but this article focuses on reviewing the Fed’s actions during previous high inflationary periods as a guide to informing the Fed’s actions in the current situation.

Above-Target Inflation

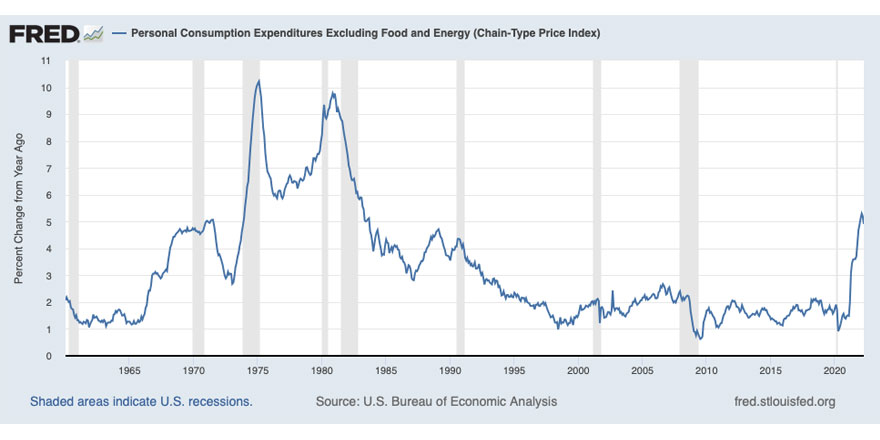

Headline PCE inflation was 6.3% in April 2022 after hitting 6.6% in March. Because of large movements in food and energy prices, we can look at the core PCE inflation rate, which excludes those two components and is a widely watched measure of underlying inflation. Core PCE inflation exceeded 5% earlier this year—coming in at 5.1% in January, 5.3% in February and 5.2% in March—though it declined to 4.9% in April.

Thus, even after excluding food and energy prices, inflation in recent months has been comparable to levels the FOMC confronted in 1974 and 1983. This can be seen in the figure below, which shows core PCE inflation from 1960 to the present.

Monetary Policy in 1974

In 1974, the FOMC focused on nonmonetary factors affecting inflation—such as government budget deficits, oil price shocks, and “excessive” price and wage increases by firms and labor unions—as opposed to monetary policy. It kept the policy rate relatively low, even in the face of rising inflation. As a result, the ex-post real interest rate (e.g., the one-year Treasury bill rate minus the inflation rate) was exceptionally low, similar to today’s ex-post real interest rate.

What followed was high and variable inflation over the next decade. Core PCE inflation remained above 5% for about 10 years, and it was nearly 10% twice during that period (in late 1974 to early 1975 and again in late 1980 to early 1981). In addition, the real economy was volatile, in part because high inflation distorts price signals, which can hamper real economic activity. Consequently, the U.S. experienced three recessions from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s.

Monetary Policy in 1983

In 1983, the FOMC took a different approach to monetary policy. The 1983 FOMC focused more on monetary factors affecting inflation and consequently kept the policy rate relatively high, even as inflation declined. In this case, the associated ex-post real interest rate was very high.

The FOMC’s policy in 1983 proved to be successful. Core PCE inflation remained below 5% for the next decade, and the real economy stabilized. One might have expected the high real interest rates to cause a recession, but that didn’t happen. The U.S. experienced a robust expansion during the remainder of the 1980s and didn’t have a recession until 1990-91.

The Lesson from 1974 and 1983

The lesson from these two different approaches to monetary policy is the importance of staying ahead of—rather than getting behind—inflation. In particular, the takeaway is that getting ahead of inflation will keep inflation low and stable and promote a strong real economy.

In the 1990s, the FOMC stayed ahead of inflation as it tightened monetary policy following the 1990-91 recession. From early 1994 to early 1995, the FOMC raised the policy rate by 300 basis points (going from 3% to 6%) in an environment where inflation was generally moderate. Similar to the 1983 experience, the associated ex-post real interest rate at that time was high. Again, the result was not a recession but instead an expansion, which lasted until 2001. In fact, one of the best periods for economic growth and labor market performance in the entire post-World War II era occurred in the second half of the 1990s.

Monetary Policy Today

These three experiences provide useful guidance for today’s monetary policymakers, namely that the approaches of 1983 and 1994 are better examples to follow. In those cases, the FOMC kept the policy rate relatively high above the inflation rate, and therefore real interest rates were relatively high. The subsequent macroeconomic performance—with respect both to inflation and to output and labor markets—was very good, which shows the merits of staying ahead of inflation as opposed to falling behind.

Today’s FOMC has taken important first steps to return inflation to target. Specifically, the FOMC has raised the policy rate by 150 basis points so far in 2022 and begun to reduce the size of the Fed’s balance sheet through the roll-off of maturing securities.While the impact of the balance sheet reduction is uncertain, Fed Governor Chris Waller provided one estimate in his speech on May 30, 2022. He asserted that the current pace of balance sheet runoff is roughly equivalent to a couple of 25-basis-point increases in the policy rate. Furthermore, its forward guidance that additional policy rate increases are likely in coming months is a deliberate step to help the FOMC more quickly move policy as necessary to bring inflation back in line with the Fed’s 2% target.

Note

- While the impact of the balance sheet reduction is uncertain, Fed Governor Chris Waller provided one estimate in his speech on May 30, 2022. He asserted that the current pace of balance sheet runoff is roughly equivalent to a couple of 25-basis-point increases in the policy rate.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us