Demographics, COVID-19 Leave Construction with Tight Labor Supply

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- As housing demand surges, the construction sector faces labor shortages; its aging native labor force never fully recovered from the impact of the global financial crisis.

- Immigrants had helped offset the decline in native labor, but this foreign-born labor force appears to have dropped with the onset of the pandemic.

- Unlike material supplies, the labor supply reflects longer-term demographic issues. And the industry may not be able to improve productivity with labor-saving technology.

The surging U.S. housing market is one of the most significant economic trends of the last few years. The effects of rising housing demand have been intensified by supply-side constraints, like a tight labor market and materials shortages.

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic doesn’t fully explain these supply shocks. The sector’s labor issues have roots in long-term demographic trends and the 2007-09 global financial crisis. Rising demand, shortages of lumber and other materials, and policy shifts brought about by the pandemic have only placed additional stress on what was already a limited labor force.

Slow Labor Supply Recovery after the Financial Crisis

Before the global financial crisis, housing starts grew from 798,000 housing units in January 1991 to a high of 2.27 million in January 2006. As a result of the crisis, housing starts fell to a low of 478,000 in April 2009.

This drop started a decadelong downward shift in a wide spectrum of housing-related investment activity. As Charles Gascon documented in a 2019 article in the Regional Economist, residential investment fell from 6.7% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) at the peak of the housing bubble in late 2005 to 2.4% of U.S. GDP five years later. While it continued to increase throughout the 2010s, residential investment reached only 3.8% of GDP in the last full pre-pandemic year. From 1947 to 2007, only 1982 and 1991—both years that experienced a recession—saw a lower level of residential investment as a share of GDP.

Preexisting Labor Market Trends

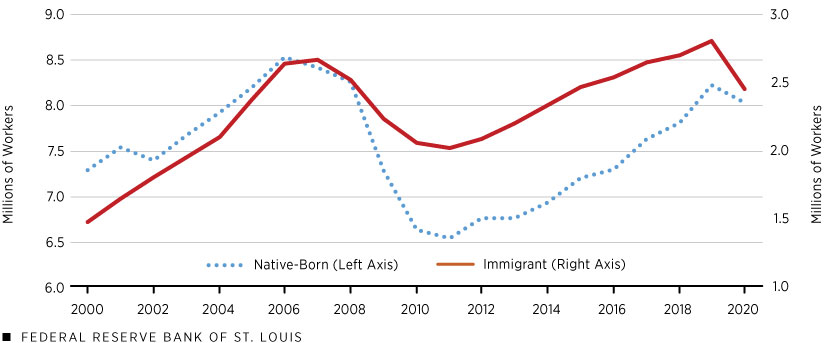

During the 2010s, sluggish real estate activity greatly affected the labor supply. Large numbers of American-born construction workers permanently left the labor force between 2006 and 2011. As the figure below shows, the number of employed native-born construction workers fell from a high of just over 8.5 million workers in 2006 to 6.5 million workers in 2011, and it took the remainder of the decade to rise to 8.2 million employed in 2019.

Employed Labor Force of the U.S. Construction Industry

SOURCES: American Community Survey and authors’ estimates.

NOTE: 2020 ACS data collection was significantly impacted by the pandemic; estimates for that year should be read cautiously.

The dislocations were even more severe when considering the entire construction labor force (which encompasses both employed and unemployed workers). The number of native-born workers fell from a high of 9.3 million in 2006 to 7.6 million in 2013, only returning to 8.6 million by 2019. National Association of Home Builders economist Natalia Siniavskaia attributes this to both demographic and macroeconomic trends (PDF): The aging of the U.S. population has resulted in decreased labor force participation rates over time, and as younger populations tend to have higher rates of educational attainment, the share of native workers involved in construction occupations has fallen.According to the fall 2021 Home Builders Institute’s Construction Labor Market Report, the proportion of construction workers ages 55 and older rose to 20.3% in 2019, while the proportion from ages 25 to 54 (prime age) fell from 72.2% in 2015 to 69% in 2019.

Meanwhile, the number of foreign-born workers in the construction industry continued to grow, despite a deep slump after the financial crisis. From 2000 to 2006, the number of immigrant workers employed in the sector grew from 1.5 million to 2.7 million. It fell to 2.0 million in 2011 but rose to above pre-crisis heights in 2018.

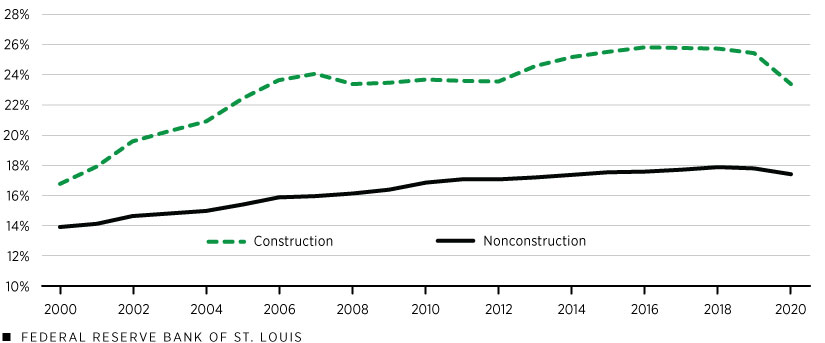

The next figure illustrates the significance of immigrants to the employed construction labor force; the proportion of such workers rose to 24.6% of the labor force in 2013 and remained above that level through 2019. However, the increasing share of foreign-born workers has not completely made up for the falling share of native-born workers in one key regard: Siniavskaia noted that foreign-born workers are less likely to work in highly skilled trades that require years of education, like electricians and inspectors. Such highly skilled trades, unsurprisingly, have experienced the most severe shortages within the sector.

Share of Immigrants in the U.S. Employed Labor Force

SOURCES: American Community Survey and authors’ estimates.

NOTE: 2020 ACS data collection was significantly impacted by the pandemic; estimates for that year should be read cautiously.

Pandemic Effects

In contrast to the slow recovery from the financial crisis, the policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic—such as relief payments and enhanced unemployment benefits—led to a rapid rebound in housing demand: Median sale prices are up over 25% since the first quarter of 2020, housing inventories are down and homes are selling faster than usual for higher than initially listed.

But the pandemic has exacerbated the construction sector’s existing supply issues and has created new ones. The physical supply chain has found itself under newfound stress, as shipping delays and reduced production capacity have produced widespread materials shortages.A May 2021 National Association of Home Builders survey found that more than 90% of builders reported experiencing at least some shortages of appliances, framing lumber, plywood, and windows and doors. The pandemic’s impact can be seen most clearly in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ producer price index, which reported sharp increases for final demand goods, less food and energy, in January 2022, with particularly high changes for construction machinery, appliances and electronic equipment.

The pandemic has also removed needed workers from the construction labor force. It is difficult to confidently estimate its effect because the pandemic also significantly disrupted data collection for the 2020 ACS, the survey we most rely on. Nonetheless, the available data (as well as anecdotal reports from business contacts) point to the pandemic continuing and exacerbating previously existing trends, with construction employment declining especially among immigrants. Indeed, all evidence points to a substantial decline in immigration to the U.S. in 2020 and 2021, with restrictions on international arrivals virtually stopping immigrant inflow.

As a result, the construction sector lost the immigrant population that helped to offset demographic aging and mass exits after the global financial crisis, just as housing activity started to surge to levels not seen since August 2006. Little wonder, then, that the construction labor market is so tight that firms have reported competitors visiting job sites to recruit high-skilled craftsmen.See the January 2022 Beige Book.

Looking Forward

There is no single, clean solution to the supply issues facing the construction industry. The optimistic case for the relief of material supply shortages is fairly straightforward: The end of pandemic disruptions should eliminate supply bottlenecks, allowing production and transportation of needed goods to return to normal levels. Yet this appears less likely than initially hoped for. Chinese exports have continued to see disruptions due to COVID-19 mitigation actions, and the conflict in Ukraine has introduced new uncertainty into global networks by raising global oil prices. Due to these issues, many firms do not expect meaningful alleviation until 2023 at the earliest.

The workforce supply issues, in contrast, reflect longer-term demographic issues. The technological solutions that have boosted productivity in other sectors may not be as available in construction, because the labor-intensive nature of the construction industry makes labor-saving tech more costly and difficult to implement. For example, while robotics has become more popular in food service and warehousing, it is still nascent technology in the construction sector and practical only at large scale. To this end, research on productivity growth in construction has found varying effects, with some aggregate evidence pointing to flat productivity, while other analyses show positive growth. Though policy changes can boost immigration and alleviate chronic shortages, the construction industry will still have to deal with the effects of an aging population and a shortage of skilled workers.

Endnotes

- According to the fall 2021 Home Builders Institute’s Construction Labor Market Report, the proportion of construction workers ages 55 and older rose to 20.3% in 2019, while the proportion from ages 25 to 54 (prime age) fell from 72.2% in 2015 to 69% in 2019.

- A May 2021 National Association of Home Builders survey found that more than 90% of builders reported experiencing at least some shortages of appliances, framing lumber, plywood, and windows and doors.

- See the January 2022 Beige Book.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us