How Economic Forecasting Works and Why It Matters

Having an idea of where the economy might be headed can help everyone from policymakers to businesses and households make better decisions about what to do today. But predicting anything isn’t easy.

“The things that occur in an economy are based on the interactions of millions and billions of human beings. Measuring the outcome of that is difficult,” said Michael McCracken. “It’s not a lab experiment, and so that makes it harder to form forecasts of the economy.”

I sat down with McCracken, a senior economic policy advisor in the St. Louis Fed’s Research division, to get his perspective on forecasting the economy. We discussed:

- What are needs and challenges for economic forecasting

- How economists account for uncertainty

- Which economic indicators are easier—and which are more difficult—to forecast than others

- What “nowcasts” are and how they’re useful

- Why economic forecasting matters

What Do You Need to Create Economic Forecasts?

Two important components for forecasting the economy are data and a model.

However, economic data are frequently based on incomplete information, such as a survey of a subset of the population, and can be revised with new information, McCracken said.

“Economic data is so messy that it helps to have some economic knowledge about relationships among variables, things that occur in the economy,” McCracken said. Knowing causal effects in economics can help guide a person in creating forecasts, he added.

For example, he said, if you know interest rates affect growth in a particular way, you’d want to include them in whatever model you’re using to forecast growth rates. It’s also helpful to have some statistical knowledge, he said, because economists are always trying to improve the models they’re using to increase forecast accuracy. They must also keep up with changes in statistical and econometric methodologies.

What Are Some Challenges in Creating Economic Forecasts?

Since data can get revised, McCracken said one challenge in creating economic forecasts is to decide what you’re forecasting in the first place.

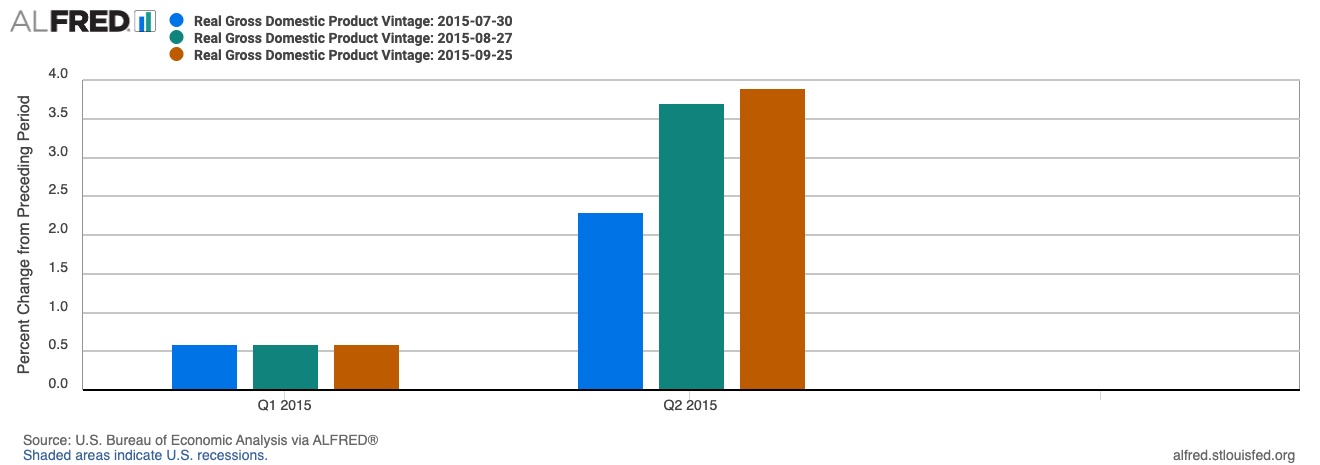

A well-known example is gross domestic product (GDP) growth. The initial estimate for a quarter’s GDP is released the month after the quarter ends, and second and third estimates are released in the next two months. (And they can be further revised later.) So, are you forecasting the GDP estimate from the initial release or a revised version?

To illustrate, the following graph from the St. Louis Fed’s archival database, ALFRED, shows the first, second and third estimates of real GDP growth for the second quarter of 2015.

Another potential challenge is tight deadlines. For example, policy decisions must be made in real time. Economists at the Federal Reserve may have only the period between one Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting and the next to come up with forecasts for various aspects of the economy, McCracken said.

Because a lot of information is available and not everything can be easily quantified, no statistical model can provide a perfect forecast, McCracken said. For that reason, judgment also factors into forecasts.

He gave an example: Let’s say your model forecasts real GDP growth of 2.8%, but you believe it’ll be lower because of some impact that can’t be quantified very well yet. So, you end up reducing your forecast from 2.8% to 2.4% based on your judgment.

How Do Economists Account for Uncertainty?

McCracken noted that estimating uncertainty’s impact on other economic variables likely would’ve been pure judgment several decades ago. But people are starting to create numerical measurements of uncertainty, which can then be used as a predictor in a model, he said.

In addition, quantifying uncertainty around a forecast has become more prevalent in the last 30 years, McCracken said. In the past, economists might’ve just said their forecast for real GDP was 2.4%, for example. But now, they might say the most likely outcome is 2.4%, but there’s a 95% probability that it’ll lie between 1.6% and 3.2%.

“That range is used to quantify the fact that we don’t really know it’s going to be 2.4%. There’s a lot of uncertainty with it, but we have some confidence that it’s going to be within that range,” he explained.

Which Economic Indicators Are Easier or More Difficult to Forecast Than Others?

McCracken gave some examples of indicators that tend to be harder or easier to forecast. They included financial series like stock market prices, which are difficult to forecast because of their volatility, and interest rates, which are easier to forecast over short horizons because they’re fairly “sticky” (slow to change).

McCracken noted that the state of the business cycle affects forecasts. The business cycle is defined as the fluctuating levels of economic activity in an economy over a period of time measured from the beginning of one recession to the beginning of the next.

A number of research papers on forecasts’ accuracy have documented that “a lot of the decline in the accuracy of your forecast occurs at the onset of a recession because the economy is acting atypically at that point,” McCracken explained.

The unemployment rate, for example, is typically pretty sticky and therefore reasonably easy to predict. “But when you get toward a recession, the unemployment rate starts to get much more volatile and harder to predict,” he said.

U.S. inflation was relatively easy to forecast for a few decades before 2021 because it was relatively low and stable, McCracken said. It became more difficult to forecast when inflation surged starting in 2021. Inflation forecasts varied a lot in 2022, but now they may be off by one-tenth or two-tenths of a percentage point with inflation back down to more stable rates, he noted.

GDP growth is hard to forecast even when the economy is performing well, McCracken said. That’s because measuring GDP is difficult and the horizon for accurately forecasting GDP growth isn’t very long. “If you can forecast two maybe three quarters ahead more accurately than just the historical mean, you’re doing well,” he said.

What Are Nowcasts, and What Do They Tell Us?

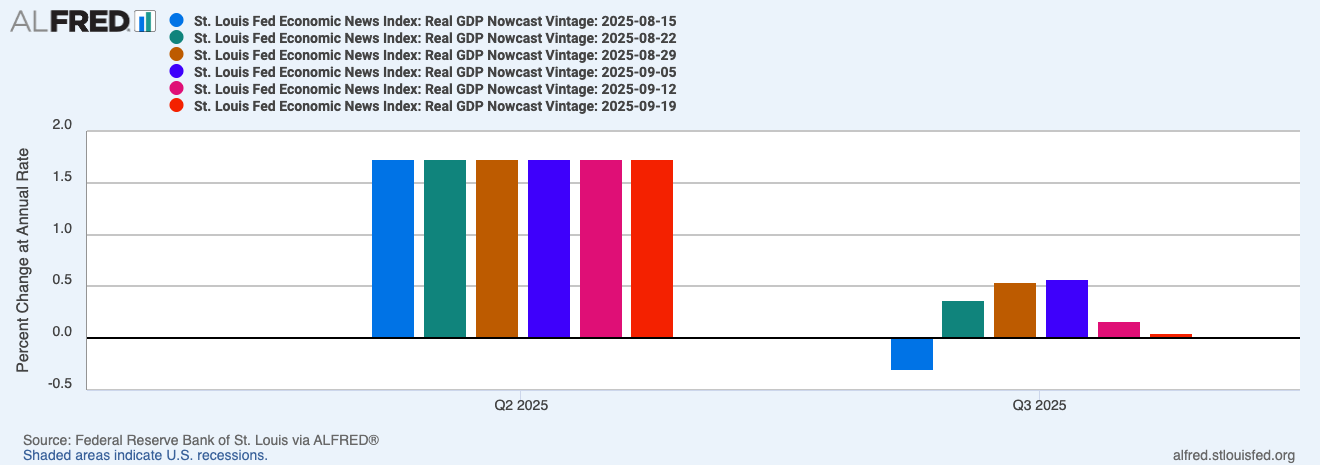

Economists sometimes want to forecast how the economy is doing in real time, which is where “nowcasts” come in. A “nowcast” is a forecast over a very short time horizon, McCracken explained.

He used real GDP growth as an example. “Before the number is released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, if you’re forecasting what the BEA is going to announce, that is a nowcast because you’re forecasting during a timeframe in which the measurement by the BEA is actually being made,” he said.

Why are nowcasts useful? Not only do they give an idea of how the economy is currently performing, but they also provide a foundation for a forecast over longer horizons, McCracken explained.

He described a real GDP nowcast called the St. Louis Fed Economic News Index (ENI). McCracken, St. Louis Fed economist Kevin Kliesen and Sean Grover, then a research assistant at the St. Louis Fed, created the ENI. The index takes key monthly economic data releases and for each release computes the “surprise,” or how much the data deviated from a forecast. The ENI weights all the surprises in a particular quarter to forecast the quarter’s real GDP growth.

The ALFRED graph below shows the evolution of the ENI projection for real GDP growth in the third quarter of 2025 (through the latest vintage available as of publication).

Why Does Economic Forecasting Matter?

Having forecasts of economic measures including real GDP growth, inflation and the unemployment rate can help the Fed’s FOMC decide what monetary policy actions to take, such as whether to adjust the target range for the federal funds rate, McCracken said.

Economic forecasts also help businesses make investment decisions, he said. Let’s say a firm wants to increase production and boost sales by building a plant that will cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take years to complete.

“Because you’re going to spend a lot of money and a lot of time building a new plant, you want that new plant to pay off in the future, which means you have to be confident that demand for your product will be substantial in the future,” he said. “And that’s a forecast.”

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us