The Human Side of Macroeconomics Motivates a Fed Economist

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors defines macroeconomics as the study of whole economies—the part of the economics field concerned with large-scale or general economic factors and how they interact. The definition goes on to outline the kinds of topics macroeconomists study, such as economic growth, inflation and the government’s role in influencing the economy.

It’s a definition that is “very thorough,” Stephanie Aaronson said in a keynote speech at the 2023 Women in Economics Symposium. Aaronson should know: She’s a senior associate director in the Division of Research and Statistics at the Board. But the Fed definition “misses what motivates many of us who study macro, especially in the policy environment,” Aaronson said, “which is that the macroeconomy has a powerful impact on people’s well-being, both over the short term and in the long run.”

—Stephanie Aaronson, senior associate director in the Division of Research and Statistics at the Federal Reserve Board

As the St. Louis Fed gears up for the 2024 Women in Economics Symposium (see the box below), we’re looking back at Aaronson’s speech and three of the examples she gave of research that has helped inform monetary policy, including by looking at the human side of macroeconomics. Aaronson, who has a research focus on labor economics in addition to monetary policy and macroeconomics, said at the start of her speech that her remarks represented her own views and were not those of the Board, the Federal Reserve System, or the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

The Effect of Women’s Increasing Presence in the Workforce

In the 2000s, many economists were expecting the labor force participation rate to rise after the 2001 recession, Aaronson said. But instead, the rate, which measures the number of people who are either working or actively seeking work as a share of the working age population, started to decline and then flattened out. (See the chart from online database FRED below.)

Why look at the labor force participation rate? The number of people who are working or looking for work is closely tied to the Fed’s maximum employment mandate, and labor force participation also is an important resource for potential output, Aaronson said.

But the labor force participation rate model that economists at the Federal Reserve Board were using at the time could not explain the participation rate’s performance, Aaronson said. The model did capture baby boomers entering their prime working years and pushing up participation.

“From studying female labor force participation, I knew that the aging of the baby boomers wasn’t the only thing that had been boosting labor force participation in recent decades,” Aaronson said. “Much of the increase was actually due to the fact that successive generations of women were working more than the ones before them.”

At the same time, successive generations of men were working a little less than previous generations, she said. But the model didn’t take those trends into account.

Aaronson and her colleagues reworked the model to include differences in labor force participation among generations. They also wrote a paper that showed women were no longer entering the workforce in increasing numbers, so the researchers didn’t expect the labor force participation rate to recover very much. Plus, they could see that once baby boomers began to retire, labor force participation would begin to decline, she said.

That’s roughly what happened, and the model has “done a reasonably good job of forecasting participation over the last 15 years or so,” Aaronson said.

“What these projections have in common is that they were aimed at improving our understanding of the economy to help the FOMC set better monetary policy within their existing framework,” Aaronson said.

Looking at How Social Programs Affect Unemployment

Shortly after Aaronson joined the Fed in the early 2000s, the FOMC was interested in whether there had been a decline in the unemployment rate that was consistent with stable inflation, Aaronson said. They were seeking to explain why there were relatively low rates of inflation at the same time unemployment rates were falling, she added.

Hear more from Stephanie Aaronson about her work at the Federal Reserve Board on a 2023 Women in Economics Podcast Series episode.

As her colleagues were putting together a June 2002 presentation for the FOMC, she discussed with them the potential impact on unemployment of various policy changes that had affected the labor market, such as reforms to the welfare system, the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit and changes to disability insurance programs.

“Some of these were things I had studied in my previous work in graduate school, albeit from sort of an applied micro perspective,” Aaronson said. She said she was able to do some “back of the envelope” calculations to help her colleagues estimate the potential impact of the policies on the unemployment rate.

“This was really an early lesson for me about how I could use my interest in social and labor market policy to contribute to our understanding of the macroeconomy,” she said.

Fiscal and Monetary Policy during Crises

Aaronson went outside her personal experience for another example of research that helped inform monetary policy and affected people’s lives, as reflected in unemployment rates.

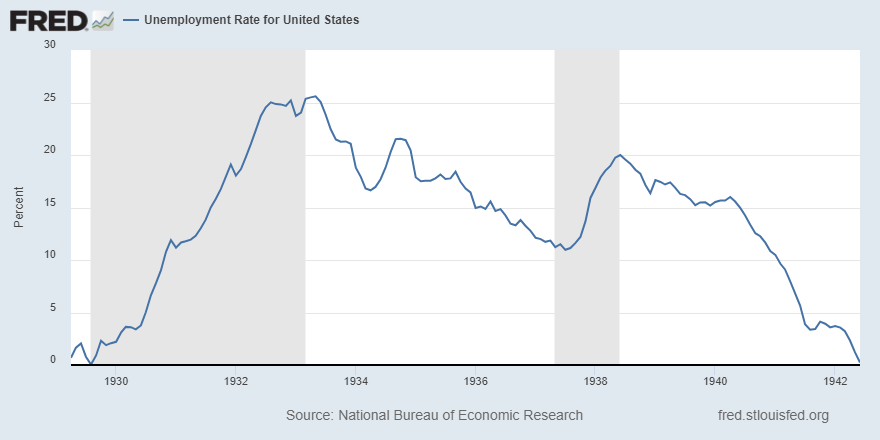

Aaronson described research that economist Ben Bernanke did on the Great Depression years before he became Fed chairman in February 2006. Work done by Bernanke, who had served as a professor at Princeton University, among other positions, provided evidence that monetary policy mistakes made because of a “lack of understanding of banking and financial crises” worsened and lengthened the Depression, Aaronson said.

As Fed chairman, Bernanke drew on that research to help manage the financial crisis in 2007-08, “with the central bank stepping up much more forcefully into its lender of last resort function and providing significant monetary accommodation,” Aaronson said. Fiscal policy also played a role in responding to the crisis and the Great Recession. The policy response was an improvement over the Great Depression response, she said. For example, unemployment topped out at 10% around the Great Recession, whereas in the Great Depression it had peaked at about 25%. (See FRED chart below.)

Economists widely believe that the fiscal response to the Great Recession was too small, resulting in a slow recovery, Aaronson said, and the experience helped shape the fiscal response to the economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Congress in its initial response to the pandemic approved about $5 trillion in spending, Aaronson said, including for expanded unemployment insurance, payments to households, loans to businesses, and support for state and local governments.

While economists will be debating the merits of both the overall spending package and its different parts for years, it’s clear that it greatly reduced the magnitude of economic suffering during the pandemic, Aaronson said, with the poverty rate in 2020 increasing only a percentage point from the 2019 rate of 10.5%.

“I think these examples make clear that macroeconomic policy has a significant impact on individual well-being,” Aaronson said.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us