Child Care Demand, Supply and the Household Decision

What to do about child care is one of the many decisions parents have to make. Do they work and send their kids to day care? Do they have relatives provide care? Do they stay home and handle the caregiving themselves?

The COVID-19 pandemic put a spotlight on the child care industry—an industry that has important implications for child development, many parents’ ability to work outside the home and the economy.

Research Officer and economist Charles Gascon explained the microeconomics of the industry at a St. Louis Fed event last year. How consistent is demand for child care and how much child care is available? What do parents consider when deciding how to handle child care needs? Read on for a recap of Gascon’s discussion of those issues.

Child Care Demand

Early Education for Kids

There is always demand for child care services, particularly for early education, Gascon noted, adding that families value quality early education regardless of their labor force status.

“We know that as kids grow up, it’s important that they interact with people their own age and they learn how to get ready to go into a classroom when they enter kindergarten,” he said.

“And so it doesn’t matter if you’re working or if you’re not working, there are still people who want their kids to be in an environment where they feel like they can learn and grow up to be better human beings.”

Labor Force Participation among Parents

Caregiving responsibilities obviously have an impact on parents’ labor force participation, Gascon noted. If someone is in the labor force, it means that person is either working or actively seeking work. The chart below shows employment-to-population ratios for men and women by age of their children for 2019 (before the pandemic), 2020 (at the start of the pandemic) and 2023 (the most recent year for which data are available).

The Ratios of Working Mothers Rise When Children Are over Age 6

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

NOTE: The ratios shown in the chart are for the native-born population and do not include the foreign-born population.

Gascon cited Bureau of Labor Statistics data from before the pandemic that showed:

- 67.5% of mothers and 92.7% of fathers with a child under 6 years old were employed.

- 77.2% of mothers and 89.9% of fathers with children ages 6-17 were employed.

The jump in the employment-to-population ratio—nearly 10 percentage points in 2019 and about 9 percentage points in 2023—among mothers who have kids ages 6-17 “suggests that once kids start getting into school and school provides those services, we see an increase in labor force participation,” Gascon said.

How Common Is the Use of “Formal” Child Care?

So, how many kids have “formal” care, or care provided by licensed child care facilities?

Gascon noted that about half of young children spend at least some time, maybe only one day a week, in a licensed child care facility. Children who are in full-time licensed care have parents who are predominantly college educated and have household income above the median, he added.

“There are a lot of disparities and a lot of mismatch to exactly how people put caregiving situations together, be it grandparents, relatives, friends, family, maybe in-home care some days, maybe it’s paid care for three days a week,” he said. “Whatever you can make work—that’s the environment which we live in.”

Gascon cited a statistic that 1 in 10 full-time workers had a child under 5 years old who required some kind of outside care in 2019, a prepandemic year he used as a benchmark.

Child Care Supply

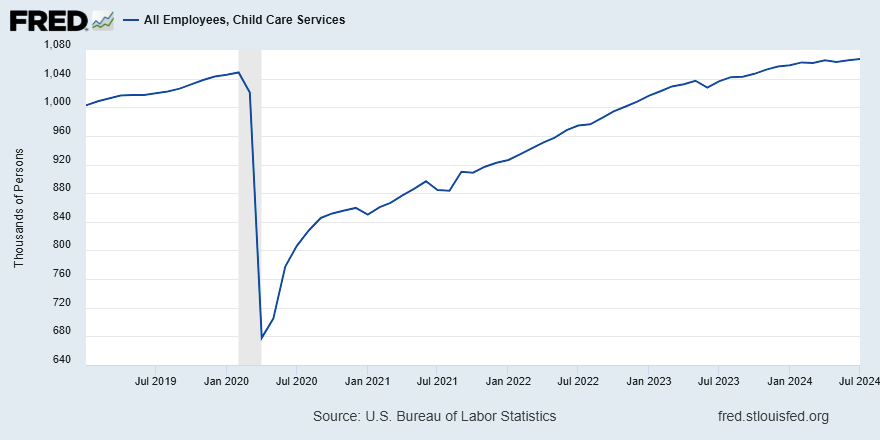

Gascon noted that the child care industry is relatively small. As of July 2024, about 1.067 million people worked in child care services, accounting for about 0.67% of total employment. Employment in the sector declined substantially early in the pandemic but has since returned to prepandemic levels, as shown in the FRED chart.

Employment in Child Care Services Is Relatively Small

Gascon estimated that the child care industry directly accounts for about 0.3% of U.S. gross domestic product, or GDP. Although small, the sector “has really broad implications” for the economy, particularly given the share of full-time workers who need some kind of outside care for their kids, he said.

Those employed in the child care industry earn relatively low wages: Nationally, the average wage for a worker in child care services was about $14 per hour in 2019, which was about 50% of the average wage among all workers depending on the state, Gascon pointed out.The $14 per hour average wage in 2019 refers to production and nonsupervisory employees in child care services. That average wage has risen to about $19 as of mid-2024, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

“That gap is necessary because that’s ultimately what allows people to go work and pay for care. If those wages end up equaling one another, the price you have to pay for child care could potentially be higher than the wages you earn,” he explained.

The child care sector is very labor intensive, Gascon said, with about 60% to 70% of provider costs attributed to employee wages and benefits.

How Households Make Child Care Decisions

Households weigh multiple factors when deciding how to accomplish work around the home, which may include child care, among other household responsibilities. Gascon discussed three questions parents consider:

- Should I do the work myself or pay someone else to do it?

- Do my earnings allow me to cover the costs of the service?

- What is the quality of my options? Do I have the skills to do a better job?

Pay for Child Care?

One reason parents may choose to pay for child care is if they believe they can receive a higher-quality service at a lower price than if they were to handle child care themselves, Gascon said. He also pointed out that child care service suppliers may have superior skills or equipment to help kids gain experiences that are important for their development.

He cited his own experience as an example, saying the workers at the child care center his kids attended “knew way more about early childhood development than I ever did, and there’s a benefit to that.”

Earnings vs. Child Care Costs?

Gascon noted that, in theory, parents should be indifferent about whether they handle child care themselves or pay for it if their wages minus child care costs are close to zero. However, he added, there are other considerations that might lead people to make different decisions.

He first mentioned that zero may be too high for some people. Paying for child care might still be beneficial over the long run, even with a period where earnings are less than the cost of child care. Lifetime earnings drop when people temporarily leave the labor force, he explained. Parents also might consider the benefits of early education from care providers if they’re more trained than the parents.

On the other hand, zero may be too low for others, Gascon said, giving a couple examples. Parents might decide the quality of outside care isn’t superior to what they could provide themselves. Or they might consider other value they get from caring for their kids, such as enjoying spending time as a family, when making child care decisions.

Quality of Child Care?

Gascon touched on several aspects of quality related to formal child care, with the common measures of quality being wages and teacher-to-child ratios. For instance, higher wages might signal that staff could provide higher quality care due to their years of experience or higher qualifications (e.g., degrees in early childhood education).

He also noted from his experience that kids tend to get sick more often in a child care environment. In addition, the operating hours and location of available child care options may not align with the parents’ work hours and location, he said.

Finally, Gascon discussed the importance of considering the children’s future outcomes, which are influenced by many factors. Again, he noted that kids might benefit from specific skills that child care providers may have that parents don’t. On the other hand, he pointed out, research has shown that parents’ spending a lot of one-on-one time with their kids leads to better future outcomes.

Gascon cited another factor that influences children’s outcomes: household income.

“If kids grow up in an environment of poverty or without money in their family, it can create a lot of adverse consequences,” he said. “And that’s not linear.”

He provided an example: If two parents each make $100,000 per year and one drops out of the labor force, the household income might still be high enough to provide the necessary resources for the children (e.g., for education). But if both parents each make $50,000 per year and one drops out of the labor force, they may no longer be able to afford the necessary resources for children. “That decline in household income may matter a lot more for those kids’ outcomes,” he explained.

Families Make Different Child Care Decisions

Parents have to consider all these factors when making choices about the right child care situation for them, Gascon noted.

“I think we have to remember that paid child care and outsourcing child care isn’t necessarily going to be right for everybody,” he said. “And I think it’s important to think about why people would be making different decisions.”

Note

- The $14 per hour average wage in 2019 refers to production and nonsupervisory employees in child care services. That average wage has risen to about $19 as of mid-2024, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us