What Are Real Values, and How Are They Used?

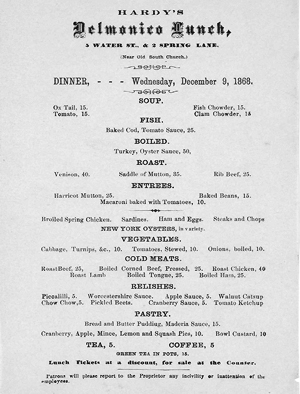

Taking a quick glance at the menu below, you might mistakenly think the prices are dollar amounts. Five dollars for a cup of coffee seems reasonable today, if a bit expensive.

However, in the winter of 1868, you could buy a cup of coffee for 5 cents, rather than $5, at Hardy’s Delmonico Lunch in Boston.

This 1868 Hardy’s Delmonico Lunch menu was retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Five cents for a cup of coffee may seem foreign today because the overall price level for goods and services—not just coffee—has increased. There has been inflation.

In other words, 5 cents buys less today than it did in the past. Or, as an economist would say, the purchasing power of 5 cents has decreased.

Hardy’s is no longer in business. However, a Starbucks that sells coffee just a few blocks away from the former Hardy’s location is. The smallest cup of coffee at this Starbucks cost $3.35 as of June 2023, a dollar amount that is 67 times larger than what Hardy’s was charging in 1868.

So, was coffee at Hardy’s that cheap?

We can use real values to answer that question by measuring the cost of coffee in terms of other goods or labor over time.

What Are Real Values?

“The real price of everything, what everything really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it,” Adam Smith wrote in his 1776 book “The Wealth of Nations.”

Nominal values represent the money used in a transaction. For example, the nominal price of coffee in 1868 was 5 cents. Real values adjust for the effects of inflation.

How Do You Calculate Real Values?

To calculate the real value of a good, like coffee, you must understand how the price has changed relative to a market basket of goods and services, which represents the items purchased by an average consumer. (Note that while real values compare the cost of an item relative to the cost of a market basket, comparing real values over long periods becomes less precise due to changes in the basket.)

If the prices of all goods and services in the basket were to rise at the same rate, the real value of any one good would be unchanged. Real values tell us when the prices of goods change at different rates than the overall basket’s.

Price indexes can help us with this. Indexes of consumer prices are the price levels of market baskets of goods and services relative to the price level at a “base” date.We can set the price of the basket to $1 at a base date just by mentally varying the size of the basket. For example, if we constructed a basket that happened to have a price of $50, a basket with one-fiftieth the quantity of goods would have a price of $1. When overall prices increase, so do price indexes.

By dividing the nominal value by the value of a price index and multiplying by 100, we can convert to a price in terms of units of the consumption basket. The following formula can be used to calculate real values:

Real value = Nominal value divided by Price index × 100

Because the consumption basket cost $1 at the base date, the formula for real value also tells us the price of good in terms of money at the base date. The table below shows two popular indexes of consumer prices and their base dates.

| Source | Price Index | Base Date | Unit after Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) | Consumer price index (CPI) | 1982-84 | 1982-84 dollars |

| Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) | Personal consumption expenditures price index (PCEPI) | 2012 | 2012 dollars |

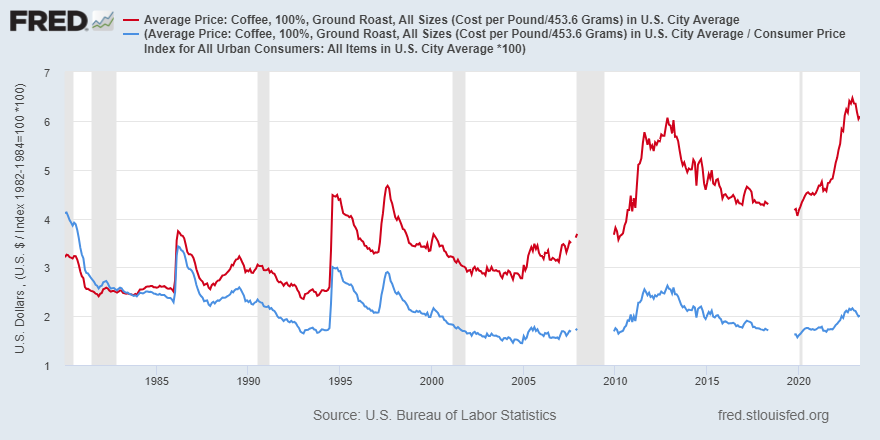

In the graph from St. Louis Fed online economic database FRED below, the blue line is the real price of one pound of coffee in terms of the CPI market basket of U.S. goods and services in 1982-84. Though the red line shows an increase in the nominal price over the last 43 years, the fact that the blue line decreased over that period shows that coffee prices haven’t risen as fast as those for the market basket of all goods and services.

How Do You Find a Value in Today’s Dollars?

What if you want to know the history of the real price of coffee—or some other price—in today’s dollars instead of in 2012 or 1982-84 dollars?

To do this, we can adjust the formula by multiplying by the value of today’s price index (instead of 100), as the Page One Economics essay, “Adjusting for Inflation,” explained using the CPI.

Current value = Original value ×Current CPI divided by Past CPI

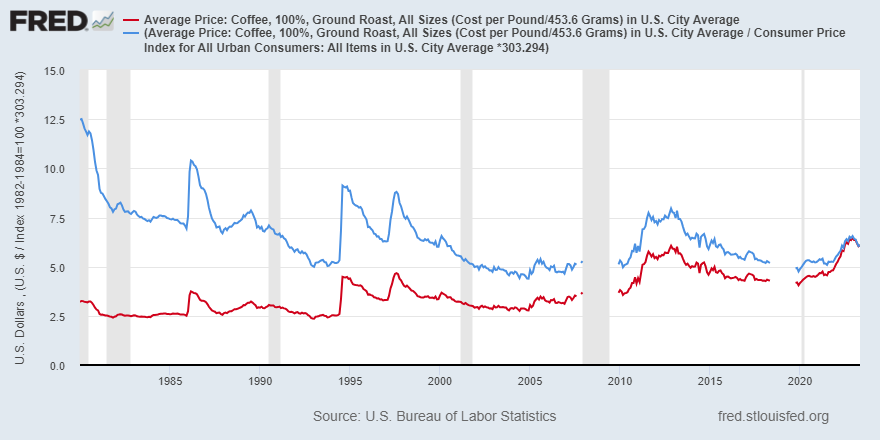

Using this new equation, we can update the blue line in the FRED graph using May 2023 as the base date instead of 1982-84. Notice the red line is not changed from the previous graph; and the real and nominal lines meet at our new base date.

In What Cases Are “Real” Values Used?

Here are a few of many ways economists, banks, the government—and now you—can use real values, plus some helpful resources.

Real GDP

Gross domestic product (GDP) is often used as a measure of the size of an economy. Comparing real GDP—rather than nominal GDP—over time ensures that you are observing changes in economic output —i.e., the real value of goods and services produced—rather than in inflation.

Check out the state of the economy in terms of real GDP (and other real variables) using the St. Louis Fed’s Macro Snapshot.

Real Interest Rates

Nominal interest rates are the percentage of a loan’s amount that the lender charges the borrower for the loan each year. Real interest rates adjust nominal interest rates for inflation to show the loss of purchasing power required to borrow money. (Or, the borrower can actually gain purchasing power if the nominal interest rate is less than the inflation rate.)

Learn more about real interest rates from an Economic Lowdown Podcast episode.

Real Wages

Wages have a certain amount of “stickiness,” which means that it takes time for them to change even when the economic environment changes. When nominal wages are left unchanged, inflation causes real wages to decrease.

Check out an On the Economy blog post on real wage growth in 2022.

Inflation-Indexed Bonds

In 1997, the U.S. Treasury Department issued inflation-indexed bonds for the first time. For these bonds, the nominal interest payments are adjusted to maintain the same real value.

Learn more about bonds using St. Louis Fed’s educational resources.

Note

- We can set the price of the basket to $1 at a base date just by mentally varying the size of the basket. For example, if we constructed a basket that happened to have a price of $50, a basket with one-fiftieth the quantity of goods would have a price of $1.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us