Job Status Changes that Help Fuel Wage Growth

After years of slow paycheck increases after the Great Recession, movements to increase minimum wages gained momentum. But the labor market situation during the COVID-19 pandemic has found employers like Walmart and McDonald’s boosting paychecks to compete for scarce workers.

Amazon’s increase brought the average starting wage for its workers to more than $18 an hour, above the $15 an hour level that activists in 2012 started pushing to make the federal minimum wage.

Wages in some cases have gone up, but so has inflation. In presentations last summer, two St. Louis Fed economists gave details on some of the forces that affect wages. Serdar Birinci outlined which job status changes have the most effect on wages. At a separate event, Victoria Gregory talked about how much wages had changed during the COVID-19 pandemic in real terms—that is, adjusted for inflation—including in different industries.

Three Types of Job Status Changes

The rates at which workers’ job status changes affects how fast the average paycheck grows. But there are different kinds of changes, and how much they affect wages varies, as Birinci explained at a Breakfast with the Fed event hosted by the St. Louis Fed’s Memphis Branch in July 2021.

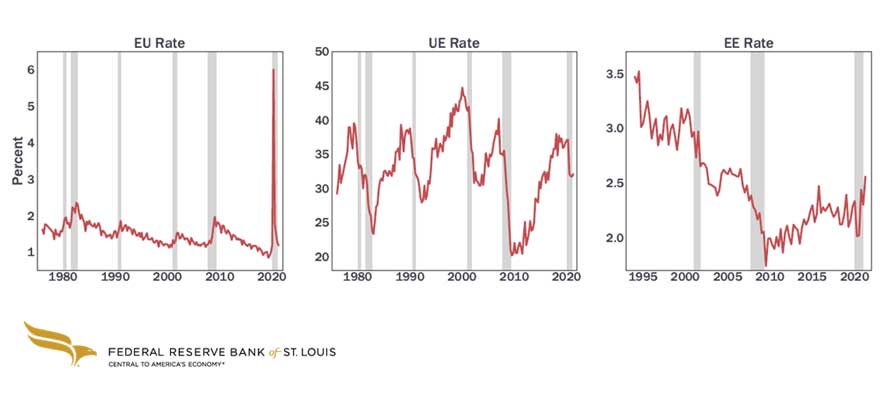

Birinci described three job status changing rates (which economists typically refer to as labor market flow rates):

- Employment to unemployment, or EU, rate: This is the job separation rate, or the rate at which employed workers leave their jobs (including by quitting or being let go) and become unemployed.

- Unemployment to employment, or UE, rate: This is the job finding rate, or the rate at which unemployed workers find a job.

- Employment to employment, or EE, rate: This is the job-to-job transition or job switching rate, or the rate at which employed workers change jobs.

Trends in U.S. Job Separation, Job Finding and Job Switching Rates

SOURCES: “Labor Markets During the Pandemic,” a July 16, 2021, presentation by Birinci, with data from the Current Population Survey and Birinci’s calculations. Gray shading indicates U.S. recessions.

Analysis of the effects of the job finding rate and the job-to-job transition rate on wage growth shows that the latter has a “much larger effect on the future wage growth in the economy,” Birinci said. He cited a 2016 paper by Giuseppe Moscarini and Fabien Postel-Vinay. In an analysis of the effect of previous job finding and job-to-job transition rates on current wage growth, the job finding rate has an “insignificant” effect that could be thought of as zero, Birinci said. By contrast, a 1% increase in the job switching rate would mean a 0.5% increase in wage growth in the future.

In this short video, Serdar Birinci discusses trends in the job switching rate following the two most recent recessions. He also touches on implications for future wage growth. For more information, see his August 2021 On the Economy blog post with Aaron Amburgey, “Job Switching Rates during a Recession.”

Why Job Switching Has a Bigger Effect on Wages

Birinci outlined two reasons for the finding that moving from unemployment to employment has a smaller influence on wage growth than job switching. For one thing, most workers are employed. Also, job finding transitions “are most likely happening at the lower end of the income distribution,” Birinci said.

“Those individuals are paid their reservation wages—the lowest wage that would convince them to find a job,” he said.

Job switching, meanwhile, has an effect not just on the wage growth of those who change jobs, but also on those who don’t. For example, in an economy where the job-to-job transition rate is higher, an employee might get an outside offer that would allow him to bargain for a raise with his current employer.

But the effect is bigger for a person who changes jobs, because many people switch when they are offered higher salaries or benefits.

“The effect of being a switcher on the wage growth is actually much larger, two times larger, than the effect of being a job stayer,” Birinci said.

“If you want to understand what would happen to wages in the future,” Birinci said, “you would be looking at, not the job finding rate—the rate at which unemployed workers find a job—but you should be looking at the rate at which employed workers change jobs.”

So if people are switching jobs regularly, and the job-to-job transition rate is “quite high,” he said, then wage growth probably will be, too.

Real Wages Increased for Some Industries in the Pandemic Period

Competition with other employers—with some workers using outside offers to bargain up their wages and some others moving to higher-paying firms, as described above—likely was driving wage increases in higher-paying industries like finance in 2020 and the first half of 2021, Gregory said at an August 2021 virtual event for St. Louis Fed employees. Her presentation, also featured at a July event sponsored by the St. Louis Fed’s Louisville Branch, included trends in earnings growth by industry.

Leisure and hospitality also saw a “particularly high pickup” in real wages, those adjusted for inflation, with a 0.88% increase pre-pandemic, between January 2019 and January 2020, rising to a 4.13% increase between July 2020 and July 2021, Gregory said. (See table.)

| Jan. 2019-Jan. 2021 (Real) % Change | July 2020-July 2021 (Real) % Change | |

|---|---|---|

| All industries | 0.56 | -1.23 |

| Construction | 0.48 | -1.46 |

| Manufacturing | 0.84 | -1.85 |

| Retail Trade | 1.57 | -0.81 |

| Transportation and warehousing | -0.33 | 0.68 |

| Financial activities | 0.95 | 1.42 |

| Professional and business services | 1.18 | -0.50 |

| Education and health services | -0.88 | -0.99 |

| Leisure and hospitality | 0.88 | 4.13 |

| Other services | -0.31 | -2.81 |

| SOURCES: “Labor Market Recovery from COVID-19 Pandemic,” an Aug. 19, 2021, presentation by Gregory, with data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Employment Statistics and Gregory’s calculations. | ||

But constraints in the number of available workers, rather than the competition for workers leading to job switching, were more likely to be the reason, she said. Industries like leisure and hospitality were understaffed and were competing with high unemployment benefits offered by the government in 2020 and part of 2021, Gregory said. “So there are a lot of incentives to increase wages to get some of these people back in,” she explained. (Given that the emergency federal unemployment benefits have ended, any wage growth in these industries after the time frame in the table may now be driven by the job switching mechanism, she said.)

Industries with rising real wages from July 2020 to July 2021 comprised only 24% of employment, Gregory said.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us