Four Considerations When Comparing the 1918-19 Influenza and COVID-19

The St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty in October during the 1918 influenza epidemic. Photo via U.S. Library of Congress

When the COVID-19 coronavirus began infecting people around the world, many started making comparisons and references to one of the world’s most deadly global pandemics: the 1918-19 outbreak of influenza, which was called the Spanish Flu.

A number of economists and economic historians have been looking at that period of time for lessons that might be applied to the current situation, St. Louis Fed economist David Wheelock said during an Aug. 28 virtual presentation.

The comparison of two highly contagious viruses seems valid. Both have left death and vast economic impact in their wakes. And some of the ways people and governments have tried to control the spread of the diseases through restrictions on social and economic activity are similar.

But as we navigate the path forward, how similar should we consider the two pandemics to be? Keep reading for four points to consider when comparing the economic effects and factors of the 1918-19 influenza pandemic with those of COVID-19.

1. The 1918-19 influenza pandemic broke out during the “Great War.”

In the spring of 1918, which marked the beginning of the influenza outbreak, the world was almost four years into global conflict that later became known as World War I.

Four million U.K. citizens were mobilized in the war, with others stepping up to take on jobs left behind by soldiers. This makes it easy to see how the United Kingdom was able to achieve an unemployment rate of less than 1% in 1918. That compares with a pre-COVID unemployment rate in the U.K. in the summer of 2019 of 3.8%.

The war demanded operational factories, and thus employees, which provided record low unemployment, but little to no social distancing. But today, no global conflict pressures businesses to stay open and hinders the pandemic response.

2. Social and economic restrictions were imposed during both pandemics in the name of public health.

The influenza pandemic of 1918-19 is thought to have infected some 500 million people, or about a third of the world’s population, and killed anywhere from 50 to 100 million people, Wheelock wrote in a May 18 article, What Can We Learn from the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918-19 for COVID-19?

When the high mortality rate of the flu became apparent, businesses, churches, schools and more began to shut down, much as they have for COVID-19. Many large public gatherings were suspended in an effort to curb the spread. However, many cities relaxed those measures after just a few weeks when flu deaths began to recede and then cases surged again, Wheelock wrote.

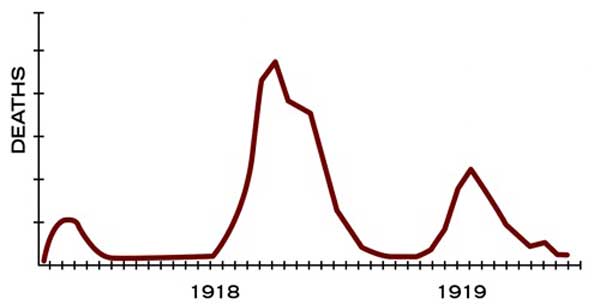

A second wave of the flu swept through in the fall of 1918 and a third wave in the spring of 1919, a full year after it first began to spread, and those waves in the U.S. were worse than the first, as can be seen in the graph from Wheelock’s presentation below.

Three Waves of Influenza Led to 625,000 U.S. Deaths

SOURCE: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Many of the nonpharmaceutical interventions in the U.S. in 1918 were not really economic in that there was less emphasis on closing businesses and factories, though businesses like theaters and bars were closed, Wheelock said at the August event.

“They didn’t have the kind of blanket shutdown of retail establishments that we saw here in the United States in early April,” Wheelock said at the Aug. 28 virtual Breakfast with the Fed presentation held by the Little Rock, Ark., Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Wheelock is a group vice president and deputy director of Research.

3. The ages of those most affected are very different.

Working-age men had the highest mortality rates during the 1918-19 outbreak in the U.S., according to a 2008 article by then-St. Louis Fed economist Thomas Garrett, Pandemic Economics: The 1918 Influenza and Its Modern-Day Implications, which is among those cited by Wheelock.

According to the article, of 272,500 male influenza deaths in 1918:

- Nearly 49% were aged 20 to 39.

- 18% were under age 5.

- 13% were over age 50.

“The fact that males aged 18 to 40 were the hardest hit by the influenza had serious economic consequences for the families that had lost their primary breadwinner,” wrote Garrett, who is now a professor at the University of Mississippi.

In comparison, death rates from COVID-19 are highest for a much older age range. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, about 203,000 people in the U.S. died due to COVID-19 as of Oct. 14, 2020. Of those, about 160,000 people, or 79%, were at least 65 years old.

4. Mobility has increased dramatically since 1918.

A large part of the spread of the 1918-19 influenza can be attributed to WWI. Garrett points out, “Not only did the mass movement of troops from around the world lead to the spread of the disease, tens of thousands of Allied and Central Power troops died as a result of the influenza pandemic rather than combat.”

The close living and working proximity of troops during the war played a big role in the spread of the pandemic among those individuals, but also among civilians as they welcomed returning soldiers home.

By the end of 1918, some 45,000 U.S. soldiers had contracted and died from the disease, a number only modestly smaller than the 53,000 American combat deaths, Wheelock wrote.

While global conflict isn’t a contributor to the spread of COVID-19, people today can travel more easily and bring disease with them. One study found that long distance flights into and within Brazil contributed to the spread of COVID-19 in that country, one of the hardest hit by the disease. The CDC recommends that people who have COVID-19 or its symptoms avoid traveling.

More to Explore

- Review: Pandemic Economics: The 1918 Influenza and Its Modern-Day Implications

- Economic Synopses: What Can We Learn from the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918-19 for COVID-19?

- COVID-19 Resources: COVID-19 Research from the St. Louis Fed

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us