Debt-to-GDP Ratio: How High Is Too High? It Depends

How much federal debt is too much? Is there a tipping point at which it becomes a big problem for a country?

One way to gauge the size of a country’s national debt is to compare it with the size of its economy—the ratio of debt to GDP. (GDP serves as a measure of an economy’s overall size and health, measuring the total market value of all of a country’s goods and services produced in a given year.)

The U.S. federal debt-to-GDP ratio was 107% late last year, and it went up to nearly 136% in the second quarter of 2020 with the passage of a coronavirus relief package. By comparison, Japan’s ratio at the end of 2019 was higher: about 200%, according to data from the Bank of Japan and Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and calculations by St. Louis Fed Economist Miguel Faria-e-Castro.

By comparing the total federal debt to the size of a country’s economy, we can see how the government can use the resources at hand to finance the debt, according to Your Guide to America’s Finances from the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Economist Miguel Faria-e-Castro’s research focuses include macroeconomics and fiscal and monetary policy. He discussed national debt in an interview last year.

In his research, Faria-e-Castro explores big questions about the economy, so we asked him about this issue last year. You can hear part of the conversation in the embedded audio.

He said the answer to the question of “how much debt is too much for a country” partly depends on three factors:

- Economic growth rates

- Whether a country has strong institutions, an independent central bank and independent monetary policy

- The level of interest rates on the debt

Why Economic Growth Rates Affect Views on Deficit Spending

Deficit spending means that a government is choosing not to raise taxes today to pay for that spending but is choosing to wait until tomorrow, Faria-e-Castro said.

When federal spending exceeds revenue, the difference is a deficit. The government mostly borrows money to make up the difference. The total national debt is an accumulation of federal deficits over time, minus any repayments of debt, among other factors.

A big consequence of deficit spending is that the fiscal burden shifts from one generation to the next, Faria-e-Castro said. That’s fine if a country’s economy is growing, because you know that the next generation will, on average, be better off than the current one, and likely able to pay a little more in taxes to decrease the debt, Faria-e-Castro said. But if a country’s economy is slowing and economic growth rates are lower than they used to be, “this starts becoming a more divisive issue.”

Investors in Some Countries’ Debt Worry about Default

Investors in some countries’ debt may be concerned about the potential for default.

Say the government of “Country X” borrows money to cover its deficits, Faria-e-Castro said. Investors—many of them international—buy that debt and then want to be repaid.

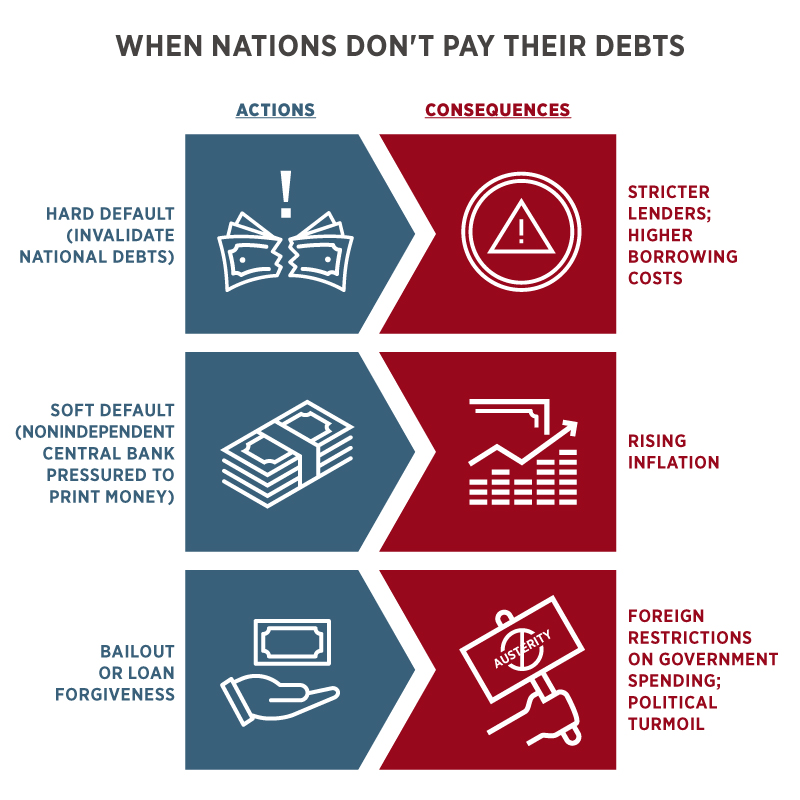

“One day, the president of Country X can just organize a press conference and just tell people, ‘OK. We’re not paying,’” Faria-e-Castro said. “That’s an outright hard default.”

But countries that take that action will have trouble borrowing again. Lenders will be less willing to lend to them and will charge higher interest rates.

There are other ways to default, some of them “kind of sneaky,” Faria-e-Castro said.

“The president of Country X can call the governor of the central bank and say, ‘OK, you have to print money to pay for this debt,’” Faria-e-Castro said.

In a country where the central bank is not an independent authority, the central bank can be pressured more easily by politicians to start printing money to pay for the country’s debt, he said.

But the flow of new money will invariably lead to high inflation in that country. That erases the value of the debt—a “soft default”—but it also typically kicks off hyperinflation, Faria-e-Castro said.

Hyperinflation is excessive inflation, with very rapid and out of control general price increases. Economists usually consider monthly inflation rates of above 50% as hyperinflation episodes, as noted in a 2018 On the Economy blog post.

Why Independent Central Banks Matter

Faria-e-Castro explained why independent central banks make a difference to a country's borrowing. Here's an excerpt of that conversation.

Countries that are not politically stable and don’t have independent central banks are not going to have very credible institutions, Faria-e-Castro said. As a consequence, they can’t borrow easily: Investors won’t be willing to lend them that much for fear of future default.

But the debt of countries with strong institutions and independent central banks—like the U.S. and Japan—doesn’t present the same risks, Faria-e-Castro said.

Few believe, for example, that the Japanese government will ever pressure the Bank of Japan to actually “print” money to pay for the country’s debt, Faria-e-Castro said.

“As a consequence, these countries can typically sustain very high levels of debt to GDP,” he said. “Because people really believe that they will be repaid, so they can keep lending.”

The strength of institutions also affects interest rates on the debt, which is another factor in determining the sustainability of high debt-to-GDP ratios. If a country has strong institutions, interest rates on the debt will be low, which means the cost of borrowing will be low, Faria-e-Castro said.

Because the institutional strength and riskiness of countries varies, there’s no rule of thumb for how high a debt-to-GDP ratio can be before it poses a risk to a country’s economy.

“At the end of the day, it all boils down to strong and independent institutions,” Faria-e-Castro said.

“A lot of economists try to study this. There’s no single measure that we can come up with… Measuring institutional strength is not obvious.”

More to Explore

- Economic Synopses: Rising Interest Rates, the Deficit, and Public Debt

- Economic Synopses: What Are the Fiscal Costs of a (Great) Recession?

- Open Vault: Where Federal Revenue Comes from and How It’s Spent

- Timely Topics: Some Basics on Sovereign Debt and Default

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us