How Can Venezuela Address Its Hyperinflation?

Hyperinflation is an economic phenomenon that occurs when inflation increases very rapidly. Although there is not a precise number that defines hyperinflation, economists typically consider monthly inflation rates of above 50 percent as hyperinflation episodes.1

During these episodes, the value of money drops dramatically as the market loses faith in the currency of a country. As a result, the currency devalues rapidly, and the economic conditions of an economy worsen dramatically:

- Unemployment increases

- Tax revenues decrease

- The cost of living goes up

All these effects translate into political instability and unrest.

History of Hyperinflation

Since the 1940s, there have been 57 episodes of hyperinflation, with the worst being the hyperinflation of Hungary in 1945, where prices were doubling every 15 hours and the highest monthly inflation rate was 4.19 × 1016 percent.2

Among other causes, hyperinflation occurs due to episodes of war, political mismanagement or the transition from a command economy in which the government owns the factors of production to a market-based economy. Usually, countries that undergo hyperinflation are characterized by high levels of government debt, which induces governments to start printing money to meet such debts. As a result, the value of the currency decreases, and a spiral effect takes hold, resulting in lost credibility on the currency and demands for higher wages, triggering even higher inflation.

Venezuela and Hyperinflation

The most recent episode of hyperinflation is Venezuela. There, inflation has been the largest in the world for the past three years.

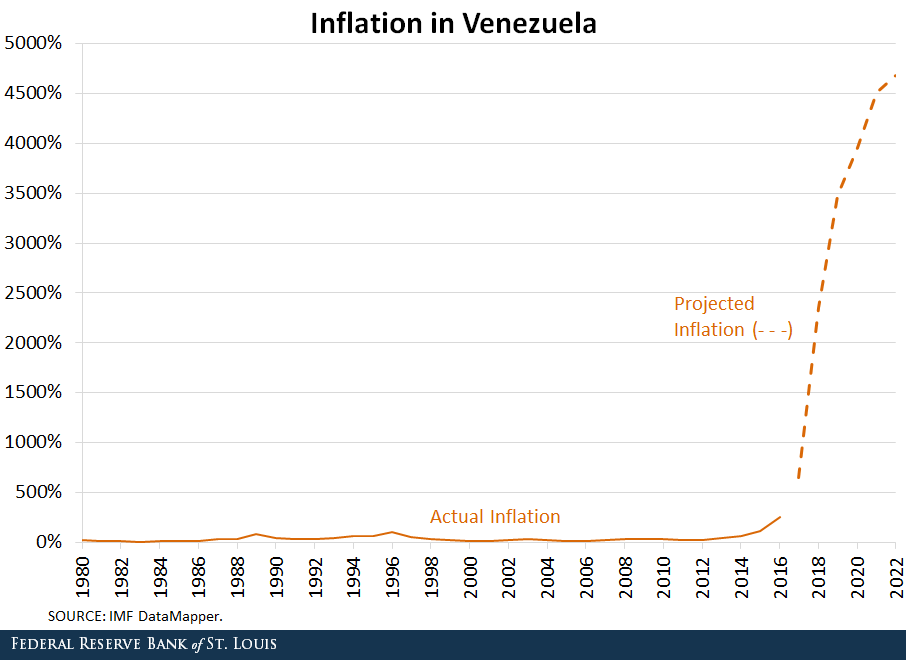

The annual inflation rate increased from 21.4 percent (versus 17.4 percent in the world) in 1980 to 652.7 percent (3.1 percent in the world) in 2017. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects it to increase to 2349.3 percent in 2018 (3.3 percent in the world).

The figure below shows the rapid increase in the annual inflation rate in Venezuela since 1980 and includes the IMF’s projections through 2022.

Both political and economic reasons are causes of rapid acceleration of inflation in Venezuela:

- On the political front, shortages of food, medicine, electricity and other necessities are causing riots and political instability.

- On the economic front, the drop in oil prices has implied a significant reduction in Venezuela’s revenues from oil’s exports.

As a result, the market values the currency as worthless, which creates difficulties for Venezuela’s government to service its foreign debt. This has translated into inflation rising rapidly and the spiral of hyperinflation taking hold.

Venezuela’s Future

The future does not look too bright either, as the IMF projects the inflation rate to reach 4684.8 percent in 2022. However, there is still hope. Brazil was in a similar situation for decades in the 20th century; its inflation rate reached over 2000 percent in 1993.3

To stabilize the economy, the Brazilian government created a virtual currency called a unit of real value (URV). URV’s intangibility and transparency made it much more trustworthy and dependable than the previously issued paper money.

Therefore, if Venezuela can adjust its large imbalances and establish some fiscal disciplines to restore people’s trust in the financial system, its hyperinflation could be tamed down eventually.

Notes and References

1 This is the definition given in Cagan, Phillip. "The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation." In Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by Milton Friedman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956.

2 Hanke, Steve. “Venezuela Enters the Record Book, Officially Hyperinflates.” Cato at Liberty, Dec. 12, 2016.

3 Costas, Ruth. “Brazil marks anniversary of inflation-busting currency.” BBC News. July 1, 2014.

Additional Resources

- FRED Blog: Hyperinflation: When Prices Go Out of Control

- Review: Shoe-Leather Costs of Inflation and Policy Credibility

- Page One Economics: Money and Inflation: A Functional Relationship

Citation

Ana Maria Santacreu and Heting Zhu, ldquoHow Can Venezuela Address Its Hyperinflation?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 18, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions