What Is the Phillips Curve (and Why Has It Flattened)?

You might’ve heard about the “Phillips curve” in recent years. Or at least some talk about whether the low unemployment rate in the U.S. could lead to higher inflation.

Understanding whether a relationship exists between these two variables—unemployment and inflation—is important when it comes to monetary policymaking.

Why is that?

The Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to promote maximum sustainable employment and price stability.

- Maximum sustainable employment can be thought of as the highest level of employment that the economy can sustain while keeping inflation stable.

- Price stability can be thought of as low and stable inflation, where inflation refers to a general, sustained upward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy. U.S. monetary policymakers believe an inflation rate of 2% is consistent with price stability, hence the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)—the Fed’s main monetary policymaking body—has to keep both sides of the mandate in mind when making decisions. But are the two sides in conflict with each other? Or are they complements?

Historical Relationship between Inflation and Unemployment

“Historically, there has often been some trade-off between inflation and unemployment,” explained Kevin Kliesen, a business economist and research officer at the St. Louis Fed. This trade-off is the so-called Phillips curve relationship.

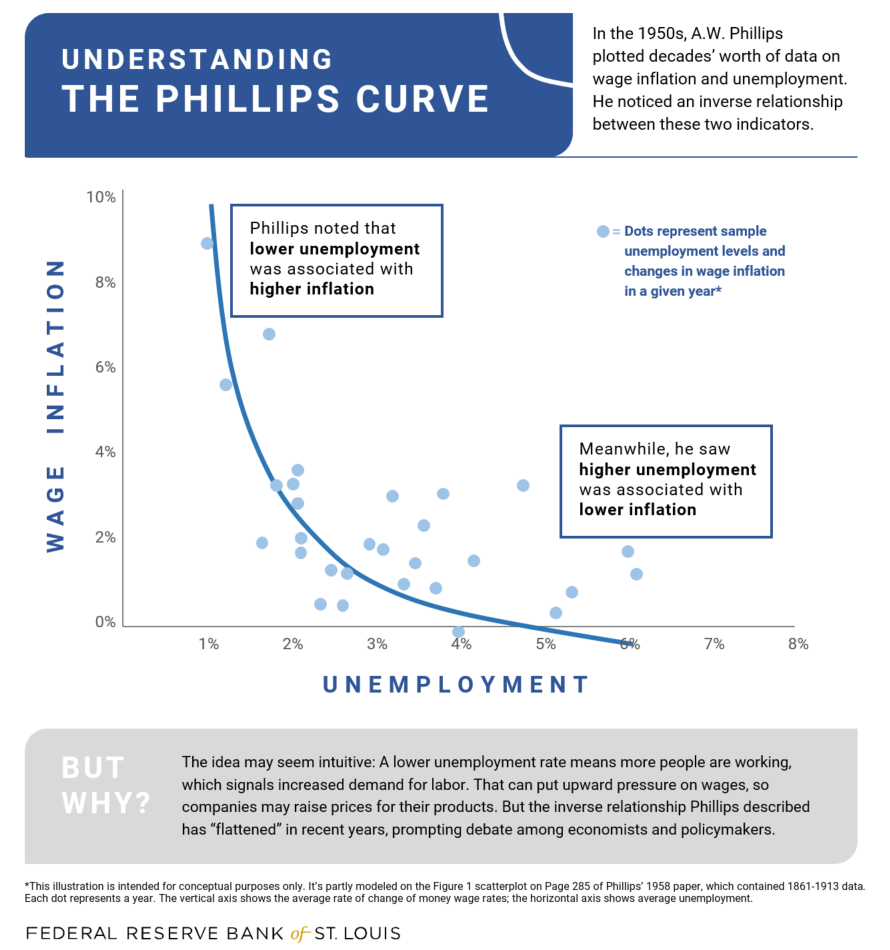

The Phillips curve is named after economist A.W. Phillips, who examined U.K. unemployment and wages from 1861-1957. Phillips found an inverse relationship between the level of unemployment and the rate of change in wages (i.e., wage inflation).Phillips, A.W. “The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957.” (PDF) Economica, November 1958, Vol. 25, Issue 100, pp. 283-99. Since his famous 1958 paper, the relationship has more generally been extended to price inflation.

Kliesen noted that the idea may seem intuitive. “A falling unemployment rate signals an increase in the demand for labor, which puts upward pressure on wages. Profit-maximizing firms then raise the prices of their products in response to rising labor costs,” he said.

Got that? The thinking behind the Phillips curve goes …

- Lower unemployment is associated with higher inflation.

- Higher unemployment is associated with lower inflation.

Then and Now

Kliesen noted that a trade-off seemed to exist in the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s. Take a look at the graph below, which shows the unemployment rate in blue and the inflation rate in red since 1950. (The inflation rate is measured using the percentage change from a year ago in the personal consumption expenditures price index.)

Figure 1: Inflation and Unemployment, Q1 1950 - Present

Over the first two decades shown in the graph, inflation was typically trending higher when unemployment was trending lower, and inflation was typically trending lower when unemployment was trending higher.

In more recent decades, however, the relationship between the two variables seems less clear.

Figure 2: The 1960s

The graph below illustrates another way to view the relationship between the two variables. It plots the inflation rate on the vertical axis versus the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis for the 1960s. You can see that lower unemployment tended to be associated with higher inflation and higher unemployment tended to be associated with lower inflation over that decade.

Figure 3: Cloud of Points

However, a similar graph that plots inflation versus unemployment beginning in 1970 does not show a clear relationship (and instead looks like a random cloud of points).

Figure 4: Recent Years

Let’s zoom in on Figure 1 above to look at recent years, starting in 2012. While the unemployment rate has declined to levels not seen in 50 years, inflation has remained low—even below the Fed’s 2% target for most of the period shown in the graph below. This suggests that the Phillips curve has “flattened,” or that the relationship might not be as strong as it once was.

Why Has the Phillips Curve Flattened?

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard has previously discussed the flattening of the empirical Phillips curve, including during an NPR interview in October 2018. “If you put it in a murder mystery framework—‘Who Killed the Phillips Curve?’—it was the Fed that killed the Phillips curve,” Bullard said.

“The Fed has been much more mindful about targeting inflation in the last 20 years,” he explained. That has resulted in lower, more stable inflation in the U.S., he said, adding “so there isn’t much of a relationship anymore between labor market performance and inflation.”

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has been asked about the Phillips curve, including during his July 2019 testimony before Congress.More recently, Chair Powell was asked at his December 2019 post-FOMC meeting press conference (PDF) about a “disconnect” between the behavior of unemployment and inflation. He explained that the relationship between resource utilization (unemployment) and inflation has gotten weaker as the Fed got control of inflation. He noted that the connection between economic slack and inflation was strong 50 years ago. However, he said that it has become “weaker and weaker and weaker to the point where it’s a faint heartbeat that you can hear now.”

In discussing why this weakening had occurred, he said, “One reason is just that inflation expectations are so settled, and that’s what we think drives inflation.”

What Does All of This Mean for Monetary Policy?

There is debate among policymakers regarding how useful the Phillips curve is as a reliable indicator of inflation—a debate that is not limited to recent years.Meade, Ellen E.; and Thornton, Daniel L. “The Phillips curve and US monetary policy: what the FOMC transcripts tell us,” Oxford Economic Papers, April 2012, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 197-216.

Why does weighing the usefulness of the Phillips curve matter? Because it could lead to different monetary policy recommendations for how best to achieve the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum sustainable employment and price stability.

As a simple example: If one policymaker thinks lower unemployment is more closely tied to higher inflation, then in periods with low unemployment, he or she might want to see higher interest rates than another monetary policymaker who doesn’t believe the two variables are closely tied.

In a February 2019 presentation, Bullard explained that “U.S. monetary policymakers and financial market participants have long relied on the Phillips curve—the correlation between labor market outcomes and inflation—to guide monetary policy.”

Given his view that this relationship has “broken down during the last two decades,” he said that “policymakers have to look elsewhere to discern the most likely direction for inflation.”

And as Chair Powell said during his July 2019 testimony, “I think we really have learned though that the economy can sustain much lower unemployment than we thought without troubling levels of inflation.”

Notes and References

- Phillips, A.W. “The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957.” (PDF). Economica, November 1958, Vol. 25, Issue 100, pp. 283-99.

- More recently, Chair Powell was asked at his December 2019 post-FOMC meeting press conference (PDF) about a “disconnect” between the behavior of unemployment and inflation. He explained that the relationship between resource utilization (unemployment) and inflation has gotten weaker as the Fed got control of inflation.

- Meade, Ellen E.; and Thornton, Daniel L. “The Phillips curve and US monetary policy: what the FOMC transcripts tell us,” Oxford Economic Papers, April 2012, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 197-216.

Editor’s Note: This post was updated to set the end dates for Figures 1, 3 and 4 to correspond to the latest quarter for which the data were available when this post was published.

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us