Are Americans Hoarding Cash, Too?

During the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, Americans have been hoarding hand sanitizer, ammunition, toilet paper, and even cash! Reports of individuals making large cash withdrawals from banks suggest that at least some members of the public are worried about the safety of their bank deposits. See, for example: https://www.wsj.com/articles/some-bank-branches-run-low-on-cash-as-customers-make-big-withdrawals-11584568519

Depositors have little to fear about the safety of their deposits, however, so long as their balances are below the current $250,000 limit on deposit insurance coverage provided by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC). Since the FDIC’s establishment in 1933, no depositor has lost a penny of FDIC-insured funds, despite the occurrence of numerous bank failures during the financial crisis and subsequent recession in 2007-09, as well as at other times. The FDIC website provides information about deposit insurance coverage.

Banking Panics during the Great Depression

The FDIC was established to protect owners of modest-sized bank accounts from losing money if their bank failed. Thousands of banks had failed during the Great Depression that began in 1929, resulting in losses for many depositors. However, deposit insurance did more than simply protect account holders from loss; it went a long way to ending the banking panics that had caused serious damage to the U.S. economy.

As bank failures swept across the country, the public became increasingly fearful of keeping their money in banks. Mass withdrawals pulled large volumes of cash from banks, which forced banks to contract their lending as they scrambled to build up reserves.

The resulting contraction in the money stock was a major cause of the Great Depression, according to Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz in their monumental A Monetary History of the United States. Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963. For more on the banking panics of 1930-33, see: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking_panics_1930_31 and https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking_panics_1931_33.

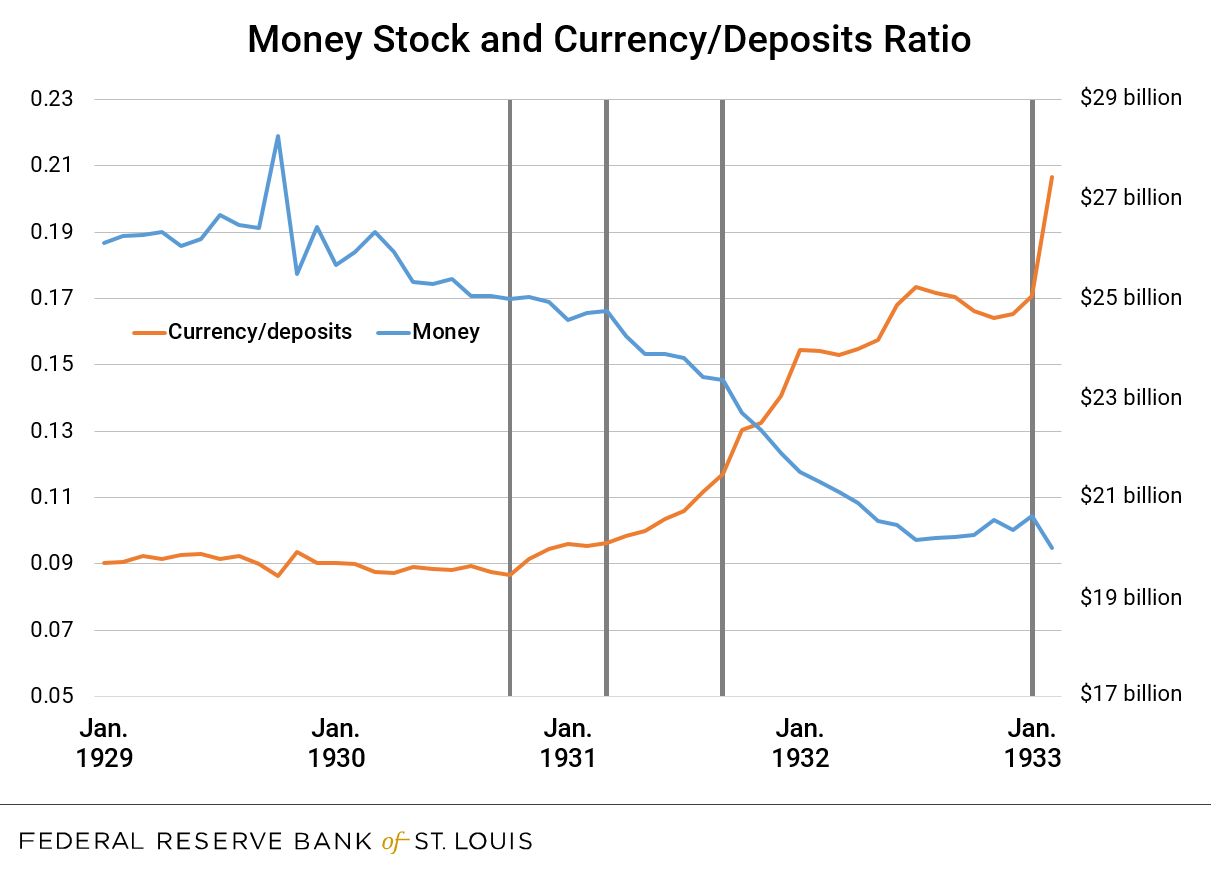

The chart illustrates Friedman and Schwartz’s main point. Beginning in late 1930, a series of increasingly serious banking panics caused the public to “run” to their banks to withdraw their deposits. This drove up the amount of currency in the hands of the public for each dollar of deposits that remained in banks.

Fearing losses of both deposits and cash, banks cut back their lending and the aggregate money stock shrank.

NOTES: This chart plots the U.S. money stock—i.e., currency in the hands of the public plus demand deposits—on the right scale, and the ratio of currency to deposits on the left scale. Vertical bars indicate months when major banking panics began, according to Friedman and Schwartz (1963).

SOURCE: The source for the data on currency, deposits, and the money stock is also Friedman and Schwartz (1963).

The Origins of Deposit Insurance

The panics culminated in a major, nationwide banking crisis in early 1933 that only ended when newly inaugurated President Franklin Roosevelt declared a national bank holiday on March 6, 1933.

The holiday lasted one week, during which time a temporary deposit insurance system was put in place. Banks were then gradually reopened. In 1934, the FDIC’s deposit insurance went into temporary effect, and then a permanent system of deposit insurance was put in place. Cash poured back into banks after the bank holiday, and banking panics ceased to be a source of instability for the U.S. economy. Something akin to a banking panic occurred during the financial crisis of 2007-09. However, the problem was not withdrawals from bank accounts, but rather a mass refusal of investors to roll over short-term debt issued by investment banks and other entities that invested in mortgage-backed and related securities. See, for example, Gary B. Gorton and Ellis W. Tallman. Fighting Financial Crises: Lessons from the Past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Deposit insurance has not been an unvarnished success. Scholars point out that deposit insurance can encourage banks to assume more risk than they would otherwise unless checked by government supervision and regulation. See, for example, Thomas M. Hoenig, “Deposit Insurance: Addressing Its Moral Hazard Effect” (PDF).

Still, the presence of federal deposit insurance, which is backed by the U.S. government, means that bank customers need not fear for the safety of their FDIC-insured deposits in U.S. banks.

So, stock up on toilet paper if you must, but rest assured that you don’t need to hoard cash.

Additional Resources

What’s unfolding now: A statement from St. Louis Fed President Jim Bullard on the COVID-19 pandemic, plus St. Louis Fed resources that may be helpful during this unprecedented time.

The recent past: Understanding the separate functions of the Federal Reserve, Treasury and FDIC amid the Great Recession, 2007-09.

Deep in the archive: Treasury regulations explaining what functions banks were allowed to perform during the 1933 bank holiday.

Notes and References

1 See, for example: wsj.com/articles/some-bank-branches-run-low-on-cash-as-customers-make-big-withdrawals-11584568519

2 The FDIC website provides information about deposit insurance coverage.

3 Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963. For more on the banking panics of 1930-33, see: federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking_panics_1930_31 and federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking_panics_1931_33.

4 Something akin to a banking panic occurred during the financial crisis of 2007-09. However, the problem was not withdrawals from bank accounts, but rather a mass refusal of investors to roll over short-term debt issued by investment banks and other entities that invested in mortgage-backed and related securities. See, for example, Gary B. Gorton and Ellis W. Tallman. Fighting Financial Crises: Lessons from the Past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

5 See, for example, Thomas M. Hoenig, “Deposit Insurance: Addressing Its Moral Hazard Effect” (PDF).

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us