Protecting Wage Earners: The Southern Roots of Bankruptcy Law

There are various types, or chapters, of bankruptcy. As I detailed in a 2018 issue of Page One Economics, Bankruptcy: When All Else Fails, two common types that individuals file are Chapter 7 (liquidation) and Chapter 13 (sometimes referred to as wage earner repayment).

In putting together that resource, I wanted to dig a little deeper into Chapter 13.

Why do United States Courts data show higher concentrations of Chapter 13 filings in Southern states? And how did the law we know today get its start—going back to the Great Depression?

A Quick Refresher on Types of Bankruptcy

Chapter 7: Liquidation

When an individual files for Chapter 7, the individual debtor’s property of value can be sold or liquidated to pay creditors (although some assets, including personal items and possibly real estate, can be exempt, depending on federal exemption provisions and the laws of the state in which the individual lives).

In Chapter 7 filings, a trustee is appointed to administer the case and liquidate the debtor's non-exempt assets. After any non-exempt assets have been distributed to creditors, any eligible remaining debt is discharged: the debtor won’t have to repay. The discharge is a permanent court order that prohibits creditors from taking any form of collection action against the debtor on discharged debts.

Chapter 13: Reorganization and Repayment

An individual filing for Chapter 13 can usually keep their property, but there are conditions.

In order to be eligible for a Chapter 13 case, the debtor needs to have some kind of regular income. The bankruptcy court must approve a repayment plan and budget that can last for a period of up to 60 months. This enables the debtor to pay off a percentage of debts during the life of the plan.

A trustee is appointed to administer the case and will evaluate the case, collect monthly payments from the debtor, and make distributions to creditors. If all the payments are made under the plan, then some debts will have been paid in full. The remainder of other debts provided for by the plan or disallowed, like credit card debts, will be discharged.

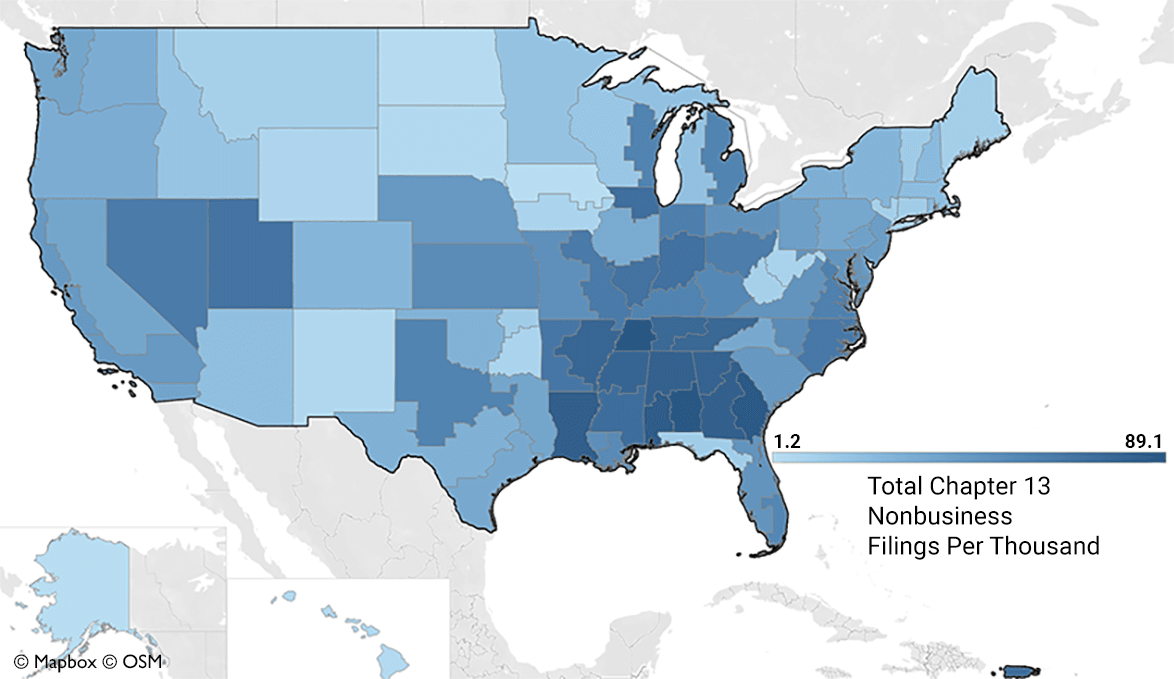

Southern States Have Higher Concentrations of Chapter 13 Filings

The United States Courts reported that for fiscal years (FY) 2006-17, about 68% of all nonbusiness bankruptcies filed in the United States were Chapter 7. United States Courts. “Just the Facts: Consumer Bankruptcy Filings, 2006-2017,” March 7, 2018. Recall that Chapter 7 cases are liquidation cases; debts are discharged relatively quickly. On the other hand, Chapter 13 cases can take up to five years as petitioners with regular income repay debt. Both 7 and 13 cases are subject to eligibility requirements.

Interestingly, for FY 2006-17, the five states with the highest Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings were Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, and Mississippi, all in the South. Two states—Tennessee and Mississippi—are partly included in the St. Louis Federal Reserve District.

(While U.S. federal court boundaries and Federal Reserve district boundaries are different, both the St. Louis Fed and the Western District of Tennessee Bankruptcy Court include Shelby County and Memphis, Tenn.)

For FY 2006-17, more than 73% of about 207,000 nonbusiness bankruptcy filings in western Tennessee were Chapter 13. That’s nearly the inverse of the national trend: in FY 2017, Chapter 13 filings represented only about 32% of some 12.8 million nonbusiness (i.e., consumer) bankruptcy filings nationally.

Bankruptcy Courts, Chapter 13 Nonbusiness Bankruptcy Filings

Notes: Per thousand of population, by district. Years ending Dec. 31, 2006-2016.

Source: United States Courts, Judiciary Data and Analysis Office Visualizations. Just the Facts: Consumer Bankruptcy Filings, 2006-2017.

The Judiciary Data and Analysis Office of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts noted in its 2018 publication that the 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA) instituted means testing for filers to move some away from Chapter 7 and toward Chapter 13.

It said, “The percentage of total filings the Chapter 7 filings accounted for has declined since 2010, whereas the percentage of total filings under Chapter 13 filings has increased.” However, the publication said, “[w]e cannot say with certainty … that BAPCPA caused this phenomenon.”

Still, I wanted to know why there were so many Chapter 13 filings in the South.

For additional information, I reached out to William Rule, senior economist in the Judicial Services Office of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. I asked him questions about Chapter 13 cases, as there are some nuances in the process and outcomes.

Rule noted that several possible reasons have been offered for this trend. For example, seasonal employment and wage fluctuation are more common in the South, as are harsher garnishment laws, which may make it easier for workers to try to work out a wage-earner plan than risk garnishment. Chapter 13, which originated in the South, appears to be taught more frequently in law schools in the South than in the North.

Rule also explained that there is generally an economic relationship between Chapter 13 filings and business cycles—out of a recession, he said, the 13s tend to increase as the job market improves. With consistent income, people can make payments on a Chapter 13 plan.

The Southern Roots of Chapter 13

Bankruptcy law history may not sound all that interesting, but Chapter 13 is an exception.

If you’re interested, Timothy Dixon and David Epstein’s 2002 article in the American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review, “Where Did Chapter 13 Come from and Where Should It Go?” is an excellent piece on the origins of bankruptcy law. Dixon, Timothy and Epstein, David. “Where Did Chapter 13 Come from and Where Should It Go?” American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review, Winter 2002.

Dixon and Epstein described how in the 1930s, as the Great Depression worsened, President Hoover called for new bankruptcy legislation to remedy existing deficits in the system. The authors said the Hastings-Michener Bill introduced in 1932 would have, among other things, offered relief to struggling wage earners—allowing them to pay their debts over a set time period and be protected from wage garnishments.

Although Congress did not enact the bill, a single line in Section 74 of later legislation opened the door slightly for wage earners to pay off their debts: “involuntary proceedings under this section shall not be taken against a wage earner.”

The authors described how a U.S. district judge in Alabama, W.I. Grubb, believed people with an income would pay off their debts if they were allowed to do so. Wage earners made up 82% of Alabama bankruptcy filers in 1931, according to Dixon and Epstein.

They said Judge Grubb named a “Special Referee in Bankruptcy” to assist debtors. That man, Valentine J. Nesbit, applied Section 74 with a very open interpretation—helping debtors get extra time while working to devise fair settlements.

The result of Grubb’s effort and Nesbit’s work was an individual reorganization, or wage earner, plan. The short version of the story is it laid the framework for what would become the Chandler Act in 1938, which created modern Chapter 13’s predecessor, Chapter XIII.

Tennessee Congressman Walter Clift Chandler, the act’s namesake, was also from the South. Dixon and Epstein said he became interested in bankruptcy from his experience as a Memphis city attorney, where he’d seen financially troubled city employees with no protection from wage garnishment as they sought to work out repayment plans.

Coming Next

This brief Chapter 13 history sheds some light on how modern bankruptcy law came to be, but it does not illuminate the differences or show what might cause certain debtors to prefer either Chapter 13 or Chapter 7. We’ll do that in our second installment (pardon the pun).

Meanwhile, for more on bankruptcy, the U.S. Courts offers an excellent Bankruptcy Basics primer.

Notes and References

1 United States Courts. “Just the Facts: Consumer Bankruptcy Filings, 2006-2017,” March 7, 2018.

2 Dixon, Timothy and Epstein, David. “Where Did Chapter 13 Come from and Where Should It Go?” American Bankruptcy Institute Law Review, Winter 2002.

Additional Resources

- Page One Economics: Bankruptcy: When All Else Fails

- Economic Education lesson: Bankruptcy Basics

- On the Economy: How Has the Bankruptcy Act Affected Bankruptcy Filings?

This blog explains everyday economics and the Fed, while also spotlighting St. Louis Fed people and programs. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us