Why U.S. House Prices Stayed Resilient While Prices Fell in Other Countries

Following decades of low and stable inflation, the period from 2021 to 2024 marked a dramatic global surge in inflation and an unprecedented cycle of monetary tightening. This recent monetary tightening cycle created a puzzle: Why did housing markets across developed countries respond so differently to the same global pressures?

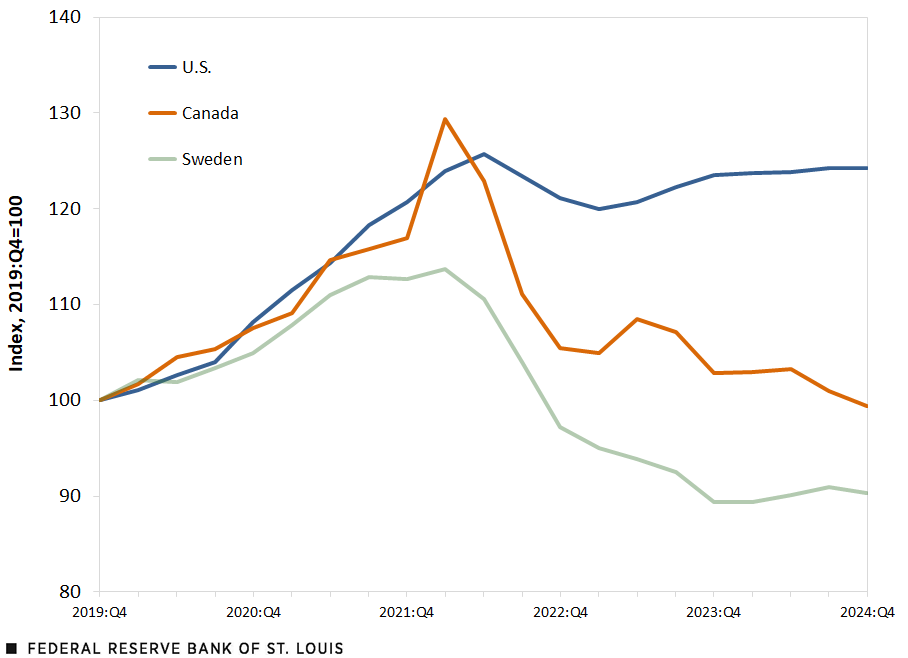

For example, during the 2020-21 expansion, the U.S. and Canada experienced house price appreciation of more than 25% while Sweden recorded increases approximately half as large. (See the first figure.) But when central banks began aggressive tightening in 2022, a striking divergence emerged. The U.S. housing market showed remarkable resilience, with only moderate price adjustments despite Federal Reserve rate hikes that pushed mortgage rates from 2.8% to 6.8%. In stark contrast, Sweden and Canada experienced sharp corrections, with Swedish prices falling substantially below their 2019 baseline levels.

Evolution of Real House Prices

SOURCES: S&P CoreLogic Case-Schiller, Bank for International Settlements and author’s calculations.

Aaron Hedlund, Kurt Mitman, Kieran Larkin and I address this question in new research.See “Mortgage Market Structure and the Transmission of Monetary Policy During the Great Inflation,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2025-016A, July 2025. Our findings reveal that the answer lies in an often overlooked institutional detail, the structure of mortgage markets.

A Tale of Different Mortgage Systems

There is substantial cross-country heterogeneity in mortgage contracts. The U.S. is dominated by long-term fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs). More than 90% of U.S. mortgages are 30-year fixed-rate contracts. When a homeowner locked in a 2.8% mortgage rate in 2020, they keep that rate for the entire loan term—even as market rates soared to 6.8%.

Countries like Sweden and Canada feature a much higher prevalence of adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) or shorter-term fixed-rate products. In Sweden, variable-rate mortgages are the most widespread product. These borrowers face immediate rate adjustments when central banks tighten policy—a homeowner who borrowed in 2020 saw their monthly payments rise almost immediately when the Riksbank raised rates. Canada occupies a middle ground with adjustable-rate mortgages that reset periodically (e.g., one- to five-year periods). These differences are not just technical details—they fundamentally alter how monetary policy flows through to the economy.

Using the Euro Area as a Laboratory: Mortgages Matter for Monetary Policy

Using prepandemic data, my co-authors and I analyzed how countries with different shares of variable-rate mortgages respond to monetary policy shocks in the euro area, i.e., the European Union countries that use the euro as their official currency. The euro area offers a unique natural experiment where multiple countries with distinct mortgage market structures all receive exactly the same monetary policy treatment. When the European Central Bank (ECB) surprises financial markets with a rate cut or hike, France (with a low share of variable-rate mortgages) and Spain (with a high share of variable-rate mortgages) experience identical policy shocks, but their housing markets respond differently based on institutional arrangements. Furthermore, the ECB sets policy for the entire region, so differences in national responses cannot be due to targeted policy reactions to country-specific economic conditions.

We identify monetary policy surprises by focusing on changes in interest rates within 45-minute windows around ECB announcements. Within this short time frame, rate movements reflect only the surprise component of policy decisions, not other economic developments. We then use these high-frequency shocks to estimate causal effects.For details, see Mattias Almgren, José-Elías Gallegos, John Kramer and Ricardo Lima’s 2022 article, “Monetary Policy and Liquidity Constraints: Evidence from the Euro Area,” in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.

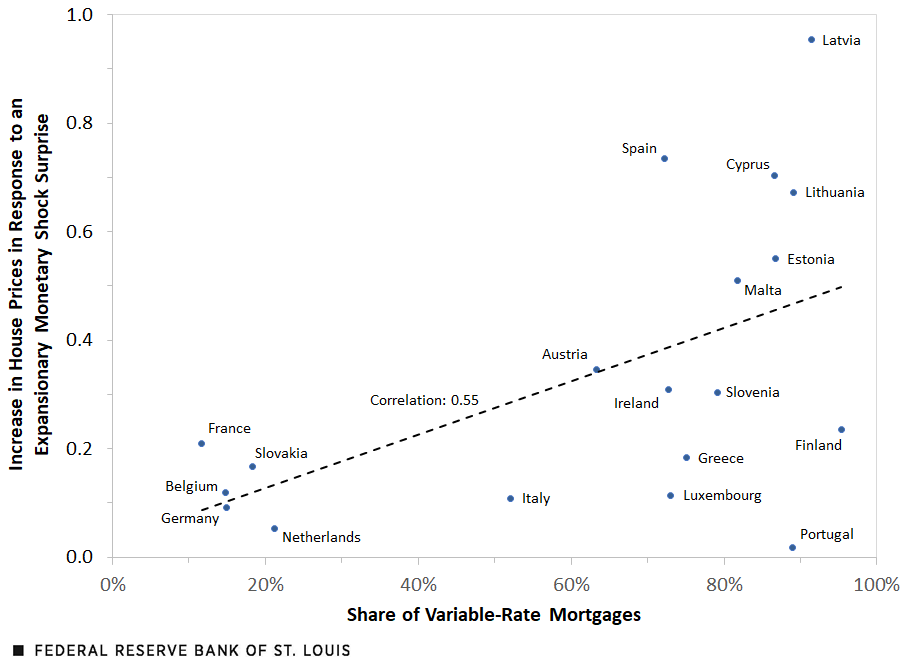

The results are striking. Euro area countries with higher shares of variable rate mortgages are associated with a stronger percent increase in house prices in response to monetary policy. (See the second figure.) When we partition countries into high and low variable-rate groups, low variable-rate countries show small, delayed responses, while high variable-rate countries experience much stronger, more immediate reactions. The correlation between variable-rate mortgage share and peak house price response reaches 0.55, providing strong evidence that institutional mortgage arrangements matter for policy effectiveness.We similarly found stronger output responses to monetary policy shocks in countries with higher shares of variable-rate mortgages. Euro area countries where variable rate loan mortgages are more common see larger changes in gross domestic product in response to monetary policy.

Mortgage Market and House Price Response to Monetary Policy Surprises

SOURCE: Hedlund, Larkin, Mitman and Ozkan (2025).

NOTES: The house price change is the change resulting from an expansionary monetary policy surprise of one standard deviation, which is about a 1.5 percentage point exogenous decrease in the central bank’s policy rate and our high-frequency instrument. The dashed line is the regression line.

These results are also consistent with the divergent paths of house prices seen between 2021 and 2024, with the price resilience of the FRM-dominated U.S. standing in contrast to the sharp corrections in ARM-dominated markets in Canada and Sweden.

The Lock-In Effect: Evidence from U.S. Household Behavior

One of the key mechanisms driving this divergence is a “housing lock-in” effect, which is unique to the fixed-rate mortgage structure. When prevailing rates rise, existing FRM homeowners are disincentivized from moving and forfeiting their low-rate mortgages. This suppresses the housing market activity and limits price declines.

The New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations provides direct evidence of this mechanism. When we examine households’ expected tenure in their current homes, a striking pattern emerges post-2022: The share of homeowners expecting to remain for two to five years increased, while those expecting to stay over 10 years fell substantially. This is precisely what we’d expect from temporary lock-in—households planning to stay put while rates are high but expecting to move once the lock-in effect dissipates.

This behavioral change manifests in market-level outcomes as well. U.S. housing transactions dropped sharply beginning in 2022, with our data showing about a 20% decline in 2022 and a 30% decline in 2023. Among the smaller pool of sellers, the distribution of “time on market” shifted markedly toward shorter durations, suggesting that those who do choose to sell are highly motivated and price aggressively to move quickly.

Conclusion

The empirical evidence demonstrates that understanding institutional details of mortgage markets is not just an academic exercise—it’s essential for predicting how economies will respond to monetary policy and for designing optimal policy responses during periods of economic turbulence.

Notes

- See “Mortgage Market Structure and the Transmission of Monetary Policy During the Great Inflation,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2025-016A, July 2025.

- For details, see Mattias Almgren, José-Elías Gallegos, John Kramer and Ricardo Lima’s 2022 article, “Monetary Policy and Liquidity Constraints: Evidence from the Euro Area,” in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics.

- We similarly found stronger output responses to monetary policy shocks in countries with higher shares of variable-rate mortgages. Euro area countries where variable rate loan mortgages are more common see larger changes in gross domestic product in response to monetary policy.

Citation

Serdar Ozkan, ldquoWhy U.S. House Prices Stayed Resilient While Prices Fell in Other Countries,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 7, 2025.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions