What Are the Long-run Trade-offs of Rent-Control Policies?

When economists evaluate policies, they typically find both positive and negative effects. These trade-offs are at the core of economics, where there is generally no free lunch. The role of the economist is to identify these trade-offs; the policymaker can, then—with full information—determine how to weigh one aspect of the trade-off against another.

These trade-offs are apparent for policies such as rent control. Targeted at providing and maintaining low-cost housing, rent-control policies have both upsides and downsides. In this case, the trade-off might initially seem transparent: lower rental costs for consumers in exchange for lower profits for landlords. However, a deeper analysis may consider the long-run effects on the overall supply and quality of rental housing.

Types of Rent-Control Policies

Broadly, there are two types of rent controls.

“First-generation” controls typically cover the entire market at the time of enactment and may freeze prices. New York City’s original rent control—a holdover from World War II-era price controls—was an example of first-generation rent control.

“Second-generation” controls cover only a subset of the rental market at the time of enactment and tend to allow more price flexibility for new leases. These rent-control policies often dictate the rate at which prices can increase on preexisting leases (usually indexed to a fraction of inflation); provide additional tenant protections against eviction; and limit mechanisms through which landlords can remove their units from control, such as major renovations, owner move-ins and condo conversions. In addition, landlords are sometimes restricted from being able to leave their units vacant or take them completely off the market arbitrarily.

While rent-control policies vary by jurisdiction, their benefits to tenants tend to be straightforward: They regulate the ability of landlords to raise rents—thereby ensuring a pool of more affordable housing—and protect tenants of controlled units from displacement.After high inflation and several years of tight rental housing markets, rent controls appealed to voters in metropolitan areas like St. Paul, Minn., which passed rent controls in 2021.

On the other hand, intermediate microeconomics textbooks depict these types of price ceiling policies as causing supply to fall and demand to increase, leading to a shortage in the market. While the reality can be more complicated, the downside of rent control is that suppressing the return on rental property investment does little to incentivize investors to increase the supply (or quality) of housing. The question for local governments and housing authorities becomes: How large are these effects?

Rent-Control Policies Can Affect Housing Stock

Despite innovations to rent-control laws meant to maintain the housing supply, economists have found that following the introduction of these policies, rental stock typically declines through channels like the conversion of rental units to owner-occupied units and major unit renovations.See Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade and Franklin Qian’s 2019 article on rent control expansion effects and Daniel Fetter’s 2016 article on rent control and homeownership during World War II. In the long run, such policies may lead to a permanent change in the housing supply mix, which could also make renting less affordable. For example, economist Daniel Fetter argued in a 2016 article that when cities responded to rent inflation during World War II with rent control, housing supply was pushed into the owned market and out of the rental market, undermining the policy’s original goal of protecting renters from fast-growing wartime housing costs. Fetter found that this supply response permanently shifted the balance of owned versus rented housing stock and increased homeownership rates over the ensuing years, sometimes to the detriment of the renters that the policy was designed to protect.

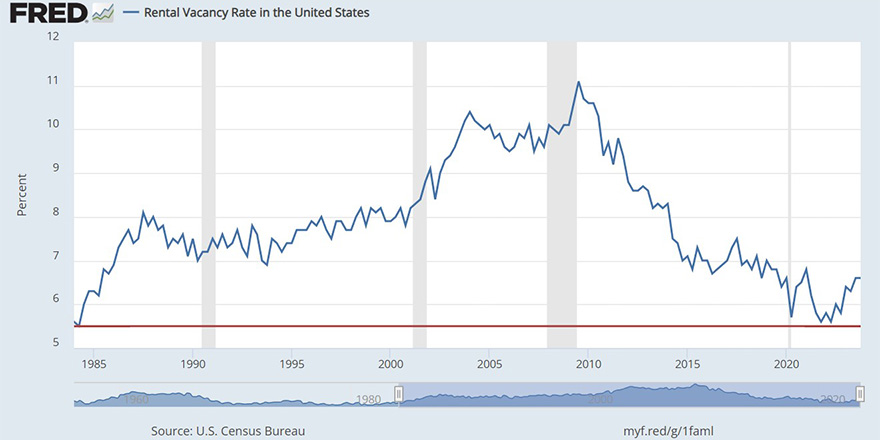

Rent-control policies’ effects on the size of the rental stock are relevant today because the rental stock is already in relatively short supply. Rental vacancy rates—the percentage of all units available for rent at a moment in time—measure the tightness of rental markets. A higher vacancy rate, particularly of nonluxury units, makes it easier for the average household to find housing, all else equal. In 2021, the overall rental vacancy rate reached 5.6%, its lowest level since 1984, although the rate has since crept back up to a still low 6.6% as of the fourth quarter of 2023. (See the figure below.)

NOTE: The red horizontal line marks the lowest vacancy rate during this period, which was 5.5% in the second quarter of 1984.

The market for affordable rental housing is even tighter. A 2023 study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (PDF) using data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey found that the “affordable” rental housing shortage was 7.3 million homes in 2021, up from 6.8 million in 2019. “Affordable” was defined as monthly rent below some fraction (typically 30%) of a benchmark income level (say, median local income).

Rent-control policies can have other downsides beyond dampening the growth of rental housing stock. Several economists found negative effects on housing quality; their studies show rent-controlled buildings or areas with large concentrations of rent-controlled units tend to have more dilapidated units, suggesting that rent control reduces landlords’ incentives to maintain their units.See Edward Glaeser and Erzo Luttmer’s 2003 article on housing under rent control; David Autor, Christopher Palmer and Parag Pathak’s 2014 article on the end of rent control in Cambridge, Mass.; and Joseph Gyourko and Peter Linneman’s 1990 article on rent controls and rental housing quality.

Weighing Trade-offs

Economists generally have found that, while rent-control policies do restrict rents at more affordable rates, they can also lead to a reduction of rental stock and maintenance, thereby exacerbating affordable housing shortages. At the same time, the tenants of controlled units can benefit from lower costs and greater neighborhood stability—as long as they don’t move.See Diamond, McQuade and Qian, 2019, and Glaeser and Luttmer, 2003.

For policymakers considering rent control, economics can help them anticipate possible effects and may even inform policy design for those who decide to pursue such policies. Given the trade-offs, policymakers must balance maintaining affordability for those with rental housing, while possibly shrinking the stock of affordable housing for others, especially when such housing is already in short supply.

Notes

- After high inflation and several years of tight rental housing markets, rent controls appealed to voters in metropolitan areas like St. Paul, Minn., which passed rent controls in 2021.

- See Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade and Franklin Qian’s 2019 article on rent control expansion effects and Daniel Fetter’s 2016 article on rent control and homeownership during World War II.

- See Edward Glaeser and Erzo Luttmer’s 2003 article on housing under rent control; David Autor, Christopher Palmer and Parag Pathak’s 2014 article on the end of rent control in Cambridge, Mass.; and Joseph Gyourko and Peter Linneman’s 1990 article on rent controls and rental housing quality.

- See Diamond, McQuade and Qian, 2019, and Glaeser and Luttmer, 2003.

Citation

Marie Hogan and Michael T. Owyang, ldquoWhat Are the Long-run Trade-offs of Rent-Control Policies?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Feb. 12, 2024.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions