Job Quits, New-Business Applications and the Postpandemic Pace of U.S. Business Formation

Within months of the COVID-19 pandemic’s initial lockdowns in 2020, new-business applications in the U.S. rose and have since remained above prepandemic levels. What drove this increase? And is it an indication of a permanent shift in business formation trends?

Similar to how housing permits are a bellwether for the housing market, new-business applications can be an indicator of future business formation. While not all applications will result in businesses with a payroll, the U.S. Census Bureau identifies high-propensity applications as those more likely to become businesses that have at least one paid employee. These new-business applications may contain information about planned wages and hiring or other characteristics predictive of formation.

Prior Research on Job Quits and Business Applications

Using regional and sectoral data through 2022, economists Ryan Decker and John Haltiwanger found new-business applications after the pandemic’s onset to be correlated with a large increase in job quits rates (sometimes referred to as the Great Resignation) observed around the same time.For more, see the fall 2023 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference draft of Decker and Haltiwanger’s paper, “Surging Business Formation in the Pandemic: Causes and Consequences?” (PDF). The authors further noted that sectors more conducive to working from home—e.g., online retail and professional services—experienced larger, more sustained jumps in new-business applications compared with their prepandemic levels. At the state and county levels, regions with large increases in new-business applications also tended to have more job quitters. Decker and Haltiwanger did not find a similar association between new-business application rates and other forms of job separation (e.g., layoffs). They argue that many of the new pandemic-period businesses were formed by people who quit their jobs and chose to start their own businesses rather than reenter the workforce as employees.

Extending the Analysis to 2024

Regional data through December 2023 and industry-level data through May 2024 are now available to update Decker and Haltiwanger’s analysis. Has the relationship between job quits and business applications persisted postpandemic, or are things going back to normal?

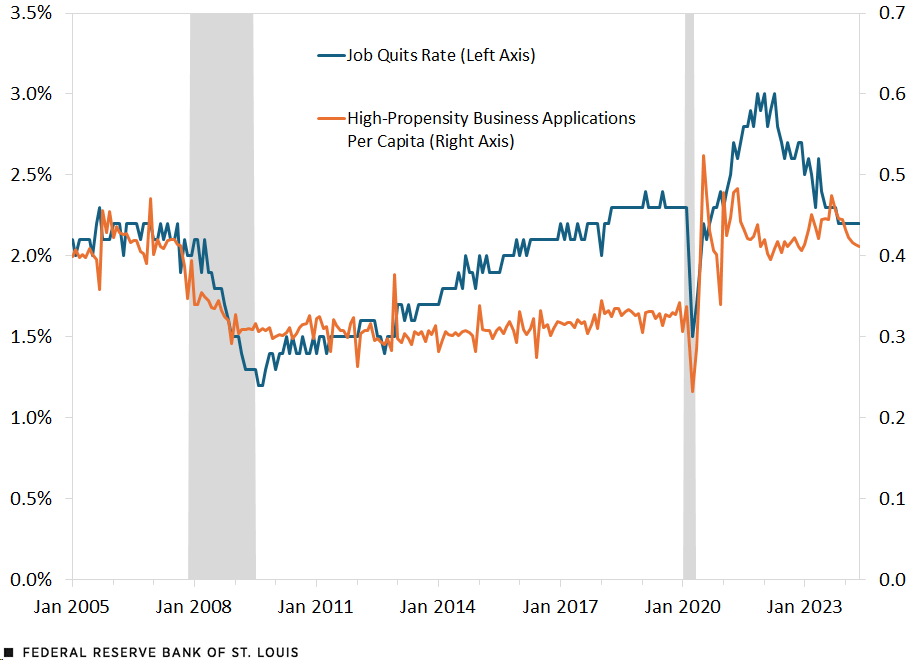

The blue line in the figure below shows the national monthly rate of job quits since 2005. The orange line shows national monthly high-propensity business applications per capita over the same period, which begins when the data first became available. Quits and applications correspond to the left and right axes, respectively.

Job Quits and Business Applications, January 2005-May 2024

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and authors’ calculations.

NOTES: Data are seasonally adjusted. Shaded areas indicate recessions.

While their month-to-month fluctuations differ, job quits and business applications often shift together around business cycle turning points. Both fell sharply during the 2007-09 Great Recession and the 2020 COVID-19 recession. Both quickly rebounded from the COVID-19 downturn, exceeding prerecession levels within months. However, while business applications exhibited an additional peak in 2023 and remained significantly above where they were in the late 2010s, job quits stayed at their peak for only a few months in late 2021 and early 2022 before returning to near their prepandemic levels.

Do Job Quits Explain the Rise in Business Applications?

To more formally compare job quits and business applications, we regressed monthly high-propensity applications per capita for U.S. states on contemporaneous state-level quits rates. We found a positive association between business applications and job quits, consistent with Decker and Haltiwanger’s conjecture that individuals quit their jobs to start new businesses during the pandemic and Great Resignation period, driving up business formation.

The strength of this relationship—which we measured by calculating the correlation between job quits and business applications at the state level within each year—varies over time, growing in magnitude during 2020 to 2023 (and particularly in 2022). This may imply that, after the lockdowns early in the pandemic, the relationship between business applications and job quits was stronger than in previous years. However, business applications have remained high through 2024 relative to the 2010s—both on aggregate and within the work-from-home-friendly industries, like professional services, on which Decker and Haltiwanger focused—while job quits have returned to previous levels. This suggests that the rise in job quits following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., the Great Resignation) cannot fully explain the persistent increase in applications for new businesses.

Do more new-business applications indicate a permanent shift in business formation levels, or simply a slow return to baseline? Business applications appear to be receding from their 2023 peak, particularly in the sectors, such as retail, that drove their initial rise. That said, because it may take one to two years following the submission of an application to determine whether the business actually materialized, the significance of this decrease for the pace of business formation overall remains to be seen.

Note

- For more, see the fall 2023 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference draft of Decker and Haltiwanger’s paper, “Surging Business Formation in the Pandemic: Causes and Consequences?” (PDF).

Citation

Michael T. Owyang and Marie Hogan, ldquoJob Quits, New-Business Applications and the Postpandemic Pace of U.S. Business Formation,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 5, 2024.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions