FOMC Actions and Recent Movements in Five-Year Inflation Expectations

During the 20 years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the inflation rate—measured by the rate of change of the consumer price index (CPI) price level—averaged 2.2%. Over the past year (from May 2020 to May 2021), the same measure of inflation averaged 6.7%. Earlier this year, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to curb inflation.

Some have argued that the modern Fed is better equipped to fight inflation than the 1970s and 1980s Fed because it has established credibility over the past few decades. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard made this argument in a recent presentation (PDF), claiming this credibility stems from an explicit commitment to inflation targeting and increased use of forward guidance. Central bank credibility affects the behavior of long-run inflation rates through expectations. The Fed has a longer-run inflation target of 2%.In January 2012, the Fed adopted an explicit inflation target of 2%, as measured by the year-over-year change in the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. We focus on the CPI inflation rate here because the TIPS compensation is measured in those terms. The CPI inflation rate is, on average, 30 basis points higher than the PCE inflation rate. If people believe the Fed's inflation objective is credible, long-run inflation expectations should not deviate much or for very long from the inflation target. Economists call this anchored expectations.

Determining Whether Inflation Expectations Are Anchored

How can we tell whether expectations are anchored? One measure of long-run inflation expectations is the breakeven inflation rates computed from Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS).One consideration in this analysis is that breakeven inflation rates are not necessarily straightforward measures of market inflation expectations. Research indicates that these measures may embed inflation and liquidity risk premia, masking the market's true expectations. (See Alexander Kupfer’s 2018 paper for a literature review.) However, the literature is undecided on the magnitude and time variation of these premia. TIPS are bonds issued by the Treasury that, in addition to the standard coupon, also pay an inflation compensation rate equal to the year-over-year CPI inflation rate. Thus, one can infer the average inflation expectations over the next five years by examining the difference between the five-year TIPS yield and the yield on a standard five-year Treasury note. An advantage of the TIPS breakeven inflation rates over survey-based inflation expectation measures is their frequency: Because they are financial instruments, the breakeven inflation rates are available daily.

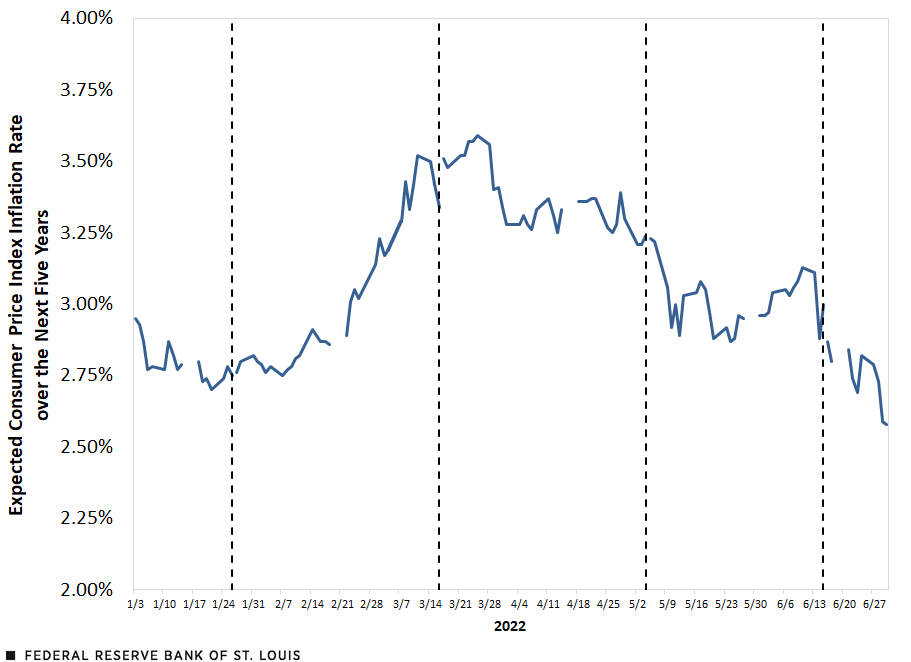

The figure plots the daily five-year breakeven inflation rate (blue line) from Jan. 3, 2022, until June 30, 2022. This rate rose from January to the end of March but fell from April through May; after a brief jump in early June, the rate declined through the end of the month, ending at about 2.6%. The black dotted lines in the figure indicate the concluding dates of the four Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings that have occurred so far this year. Movement of the breakeven inflation rate subsequent to these meetings can provide insights on how the market's long-term inflation expectations responded to the FOMC's policy actions.

Recent FOMC Meetings and the Five-Year Breakeven Inflation Rate

SOURCES: Federal Reserve Board and FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data).

NOTES: Data are from Jan. 3, 2022, to June 30, 2022. Vertical dashed lines indicate the concluding day of FOMC meetings.

At the first meeting, which concluded on Jan. 26, the FOMC kept the target range for the federal funds rate at 0%-0.25%. This policy announcement did not take any imminent action to curb inflation, and the five-year breakeven inflation rate increased over the following weeks. At the second meeting, which concluded on March 16, the FOMC raised the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points to 0.25%-0.50% and suggested that future increases might be appropriate. On the day of this policy announcement, we saw a sharp dip in the breakeven inflation rate, perhaps indicating a market response to the Fed's implementation of a rate hike cycle. Though the breakeven inflation rate did tick back up in the following two weeks, it then fell and tapered off through April and early May. At the third meeting, which concluded on May 4, the FOMC raised the target range for the federal funds rate by 50 basis points to 0.75%-1.00% and indicated that future increases would be likely. Following this more substantial monetary policy action, the breakeven inflation rate fell and stayed at a relatively lower level through May. At the fourth meeting, which concluded June 15, the FOMC raised the target range for the federal funds rate by 75 basis points to 1.50%-1.75%. The breakeven inflation rate has declined since that most recent meeting.

Long-run inflation expectations have not retreated to the Fed's long-run inflation target. However, changes in the breakeven inflation rate since the Fed's recent tightening actions suggest inflation expectations—at least in the long term—are moving back toward the target.

NOTES

1 St. Louis Fed President James Bullard made this argument in a recent presentation (PDF), claiming this credibility stems from an explicit commitment to inflation targeting and increased use of forward guidance.

2 In January 2012, the Fed adopted an explicit inflation target of 2%, as measured by the year-over-year change in the headline personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index. We focus on the CPI inflation rate here because the TIPS compensation is measured in those terms. The CPI inflation rate is, on average, 30 basis points higher than the PCE inflation rate.

3 One consideration in this analysis is that breakeven inflation rates are not necessarily straightforward measures of market inflation expectations. Research indicates that these measures may embed inflation and liquidity risk premia, masking the market's true expectations. (See Alexander Kupfer’s 2018 paper for a literature review.) However, the literature is undecided on the magnitude and time variation of these premia.

Citation

Michael T. Owyang and Julie Bennett, ldquoFOMC Actions and Recent Movements in Five-Year Inflation Expectations,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, July 7, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions