The Allocation of Immigrant Talent across Countries: Employment Gaps

Foreign-born individuals currently constitute a significant fraction of population across countries. For instance, they account for close to 20% of population in Canada and around 13% of population in the U.S., Germany and the U.K. Despite their significant presence, immigrant workers continue to face considerable barriers in navigating the labor market.

In our recent working paper, “The Allocation of Immigrant Talent: Macroeconomic Implications for the U.S. and across Countries,” we studied macroeconomic, distributional and policy implications of immigrant labor market barriers in the U.S. and across countries. In an Economic Synopses essay published this month, we summarized our findings on the distribution of employment and earnings of immigrants and natives in the U.S. In this blog post, we document cross-country differences in the distribution of employment between natives and immigrants across occupations.

Immigrant-Native Gaps in Employment across Occupations

In particular, in our working paper, we used individual-level data from the Luxembourg Income Study to quantify the barriers to immigrants’ economic integration across 19 countries. The following figures, based on a panel from our working paper, plot cross-country differences in labor market allocations between native and immigrant workers for each of the following occupation groups:

- nonroutine cognitive, which includes management and professional occupations

- nonroutine manual, which includes jobs like health aides and food workers

- routine cognitive, which includes jobs like retail sales and clerical workers

- routine manual, which includes jobs like construction and assembly workers

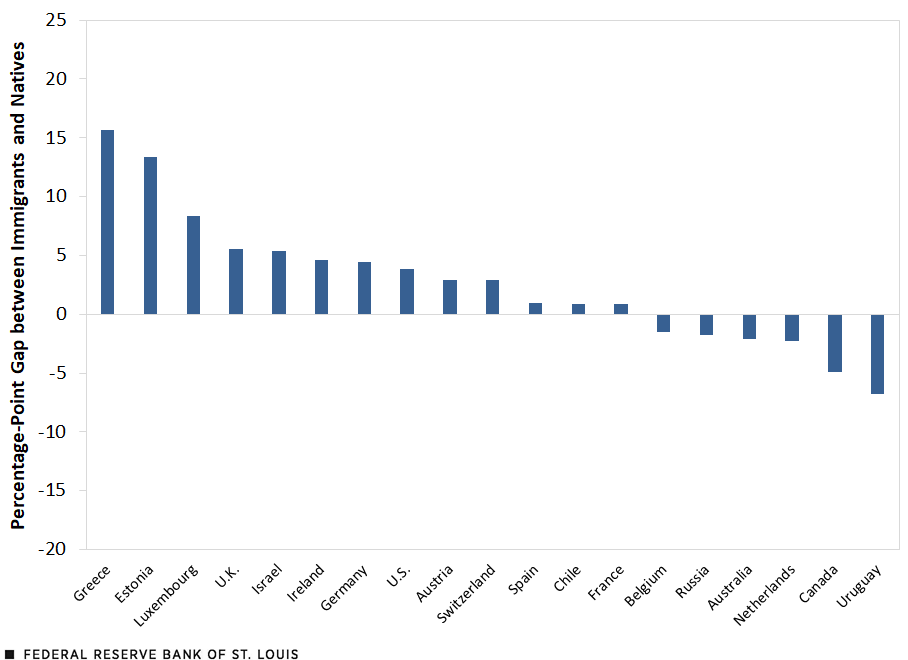

These four occupation groups are shown in the second figure through the fifth figure in that order. In addition, nonemploymentNonemployment comprises unemployed workers and people who aren’t participating in the labor force. is plotted in the first figure.

The y-axis of the figure for a given occupation group gives the percentage-point difference between the percentages of native and immigrant workers, respectively, engaged in each occupation group in a particular country. For example, in the second figure, we subtract the percentage of immigrant workers in nonroutine cognitive occupations among all immigrant workers in a given country from the percentage of natives in this type of occupation among all natives in that same country.

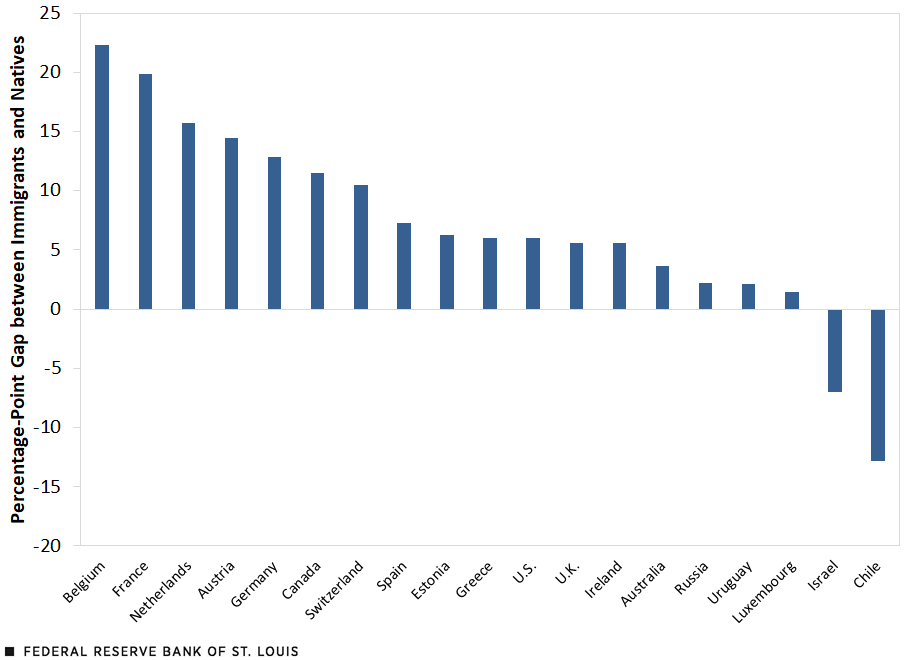

Differences in the Allocation of Immigrants and Natives in Nonemployment

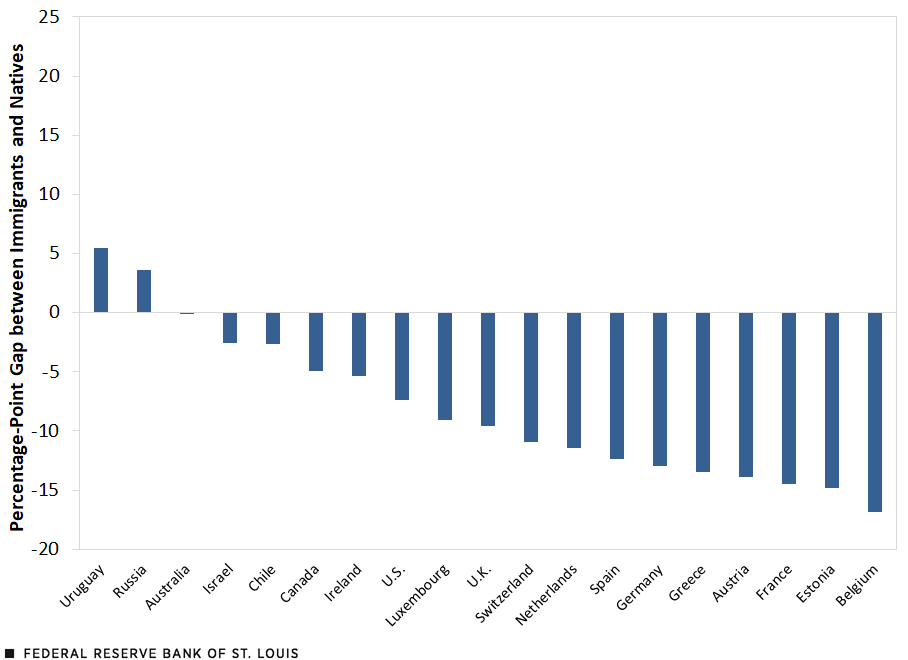

Differences in the Allocation of Immigrants and Natives in Nonroutine Cognitive Occupations

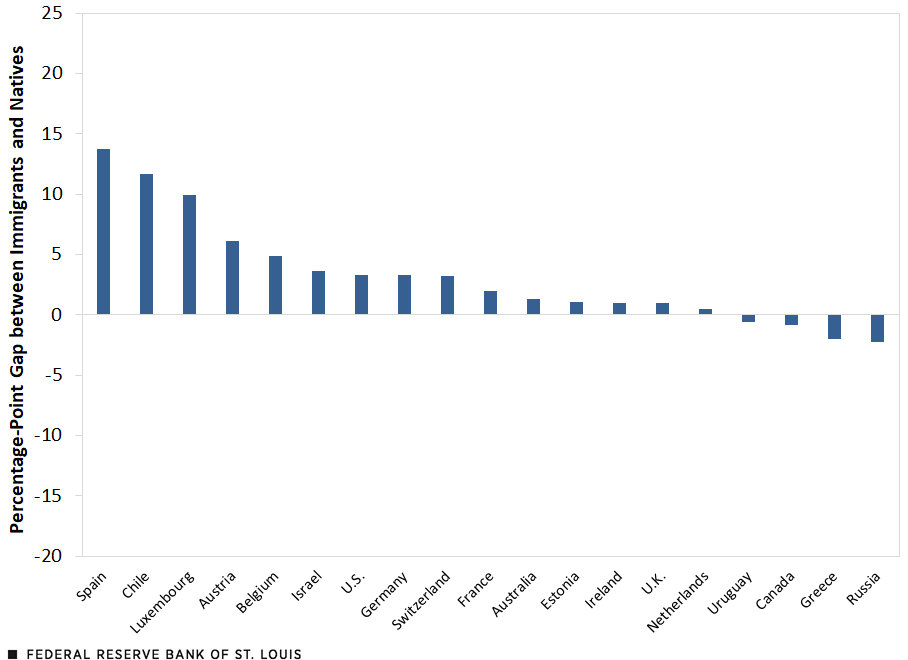

Differences in the Allocation of Immigrants and Natives in Nonroutine Manual Occupations

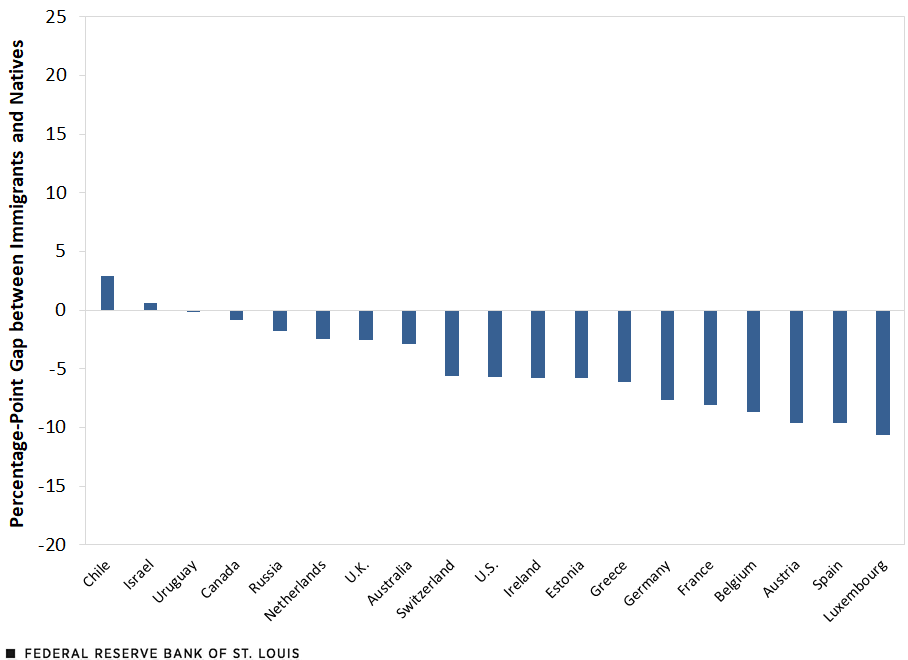

Differences in the Allocation of Immigrants and Natives in Routine Cognitive Occupations

Differences in the Allocation of Immigrants and Natives in Routine Manual Occupations

SOURCE FOR THE FIVE FIGURES: Birinci, Leibovici and See, revised June 2022.

NOTES: A positive gap indicates that immigrants are overrepresented in that occupational group, while a negative gap indicates that they are underrepresented in that group.

The first figure shows that, with the exceptions of Israel and Chile, immigrants are generally more likely to be nonemployed—that is, to belong in the nonemployment group—than natives. The gap in nonemployment varies greatly across countries, ranging from around 22 percentage points for Belgium to fewer than 5 percentage points for Australia, Russia, Uruguay and Luxembourg.

Turning our attention to the second figure, the prevalence of negative immigrant-native differences indicates that immigrant workers are, in most countries, less likely to be in nonroutine cognitive occupations—think doctors or engineers—than their native counterparts. Australia is a notable exception, where the gap is extremely small—almost zero. A similar underrepresentation of immigrants can be found in routine cognitive occupations, as illustrated in the fourth figure.

Meanwhile, the third figure shows that immigrants are overrepresented in nonroutine manual occupations—think child care or food service workers—though the gaps are minor for some countries, including the Netherlands and the U.K. As observed from the fifth figure, immigrant workers are also more likely than their native counterparts to be in routine manual occupations.

Immigrants Overrepresented in Lower-Paying Jobs

Taken together, the second and third figures are of particular importance, since nonroutine cognitive occupations have the highest average earnings for all countries, while nonroutine manual occupations have the lowest average earnings. The U.S. falls into the lower tail of the distribution of the immigrant-native employment gap in nonroutine cognitive occupations, with a difference of about -7 percentage points. The country falls in the midrange of the gap for nonroutine manual occupations, with a difference of close to 4 percentage points—similar to Ireland and Germany.

Differences May Reflect Additional Barriers

Overall, our examination of cross-country microdata suggests that in numerous countries immigrants are overrepresented in lower-paying manual occupations and underrepresented in the higher-paying cognitive ones, though the magnitude of immigrant-native difference varies by country. Importantly, we emphasize that these differences may reflect additional barriers that immigrants face and the skills they have relative to their native counterparts. To differentiate these two margins, we use the economic model in our working paper.

Note

- Nonemployment comprises unemployed workers and people who aren’t participating in the labor force.

Citation

Serdar Birinci, Fernando Leibovici and Kurt See, ldquoThe Allocation of Immigrant Talent across Countries: Employment Gaps,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 11, 2022.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions