Gender and Labor during COVID-19

Women’s employment during the COVID-19 pandemic was far more affected than men’s, according to an analysis by St. Louis Fed economist and Research Officer Alexander Monge-Naranjo and Research Associate Qiuhan Sun. The authors identified two main factors that influenced unemployment rates for women: the nature of women’s jobs and their family circumstances.

Why This Recession Differed

Rather than being a typical recession, the COVID-19-related downturn wasn’t sparked by a financial crisis but by government policies and private sector responses to curbing the novel coronavirus. Large swaths of the service sector were affected by physical distancing and lockdowns. The restrictions severely impacted jobs and industries that require close personal contact, including health care, education and hospitality; those occupations tend to have large shares of women employees, the authors wrote.

“This is quite different from previous recessions that disproportionately reduced jobs in the traditionally male-dominated construction, transportation and manufacturing sectors,” Monge-Naranjo and Sun.

For instance, during the Great Recession, which fell within the May 2007 to November 2009 time frame, the unemployment rate for men increased to 11% from 4.6%; for women, it jumped to 8.6% from 4.4%. By contrast, in January 2020, the unemployment rate for both genders was 3.5%; in April 2020, it spiked to 16.1% for women and 13.6% for men, the authors noted.

“In addition, even in the modern era, caring for children and the elderly falls disproportionately on women. So, the closures of schools and all other centers that care for children and seniors are likely to have further reduced—perhaps enormously—the labor market opportunity for many women,” they wrote.

Conflicting Trends

Two trends play into the pandemic-related labor outcomes. For several decades, highly educated women have been entering the labor market. Yet women still make up a very large and stable share of those who hold part-time jobs, which are relatively insecure, the authors noted.

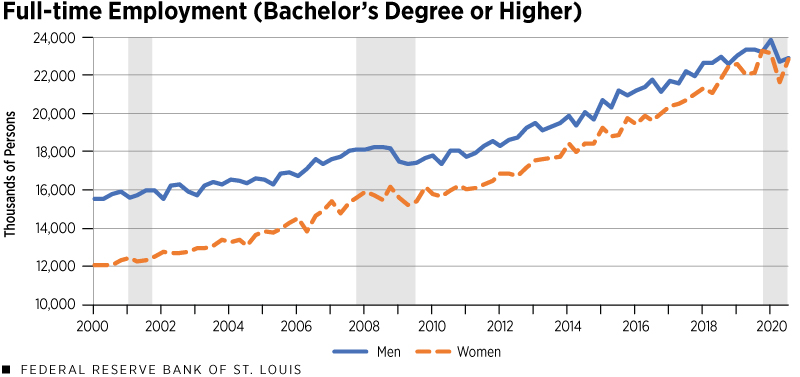

The figure above shows the numbers of men and women employed full time who were older than 25 and had at least a bachelor’s degree. In 2000, women in this group represented 44% of the labor market. By late 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic, they reached parity with men, they noted.

Since white-collar jobs can be performed more easily from home, it would seem that the COVID-19 crisis should not have impacted the labor market for women more severely than for men, Monge-Naranjo and Sun observed.

“All the asymmetries in the upper end of skill distribution might be explained by an uneven division of labor inside households, in terms of caring for children, the elderly and the sick,” they wrote.

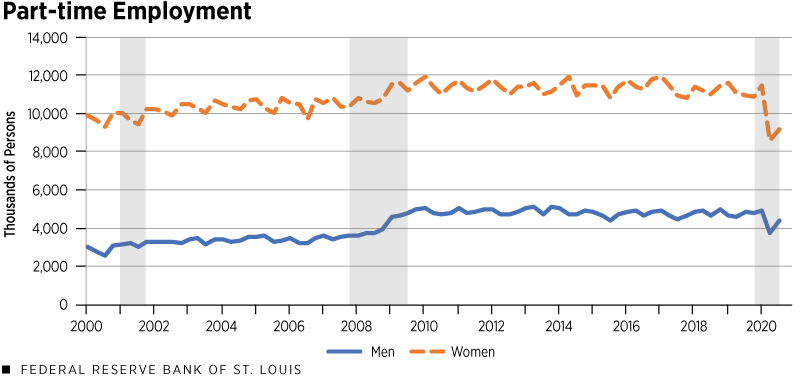

Women also make up a large and persistent share of those who hold part-time jobs, particularly in the lower end of skill distribution. The figure below shows the numbers of men and women working part time who were older than 25. These part-time jobs tend to be somewhat insecure, and many are in service sectors that also demand a great deal of physical contact with workers and customers, the authors pointed out.

“COVID-19 was probably the perfect storm for many women in these jobs, especially those with families,” Monge-Naranjo and Sun wrote.

The figure shows a sharp drop in these types of jobs, and, so far, a much slower labor recovery for women than for men. The unemployment rate also increased substantially more for women of color than for white women, they wrote.

“In sum, in addition to the remarkable asymmetry between men’s and women’s job losses, the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities for women in the labor force, as dictated by their skill levels and occupations,” the authors concluded.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: COVID-19’s Effects on Dual-Earning Households

- On the Economy: Are We Really in This Together? The Divided Nature of the COVID-19 Pandemic

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions