Does Bargaining Help Explain Wage Inequality?

Are wage negotiations by individuals more prevalent in certain occupations? And if so, how might these negotiations affect wages across occupations?

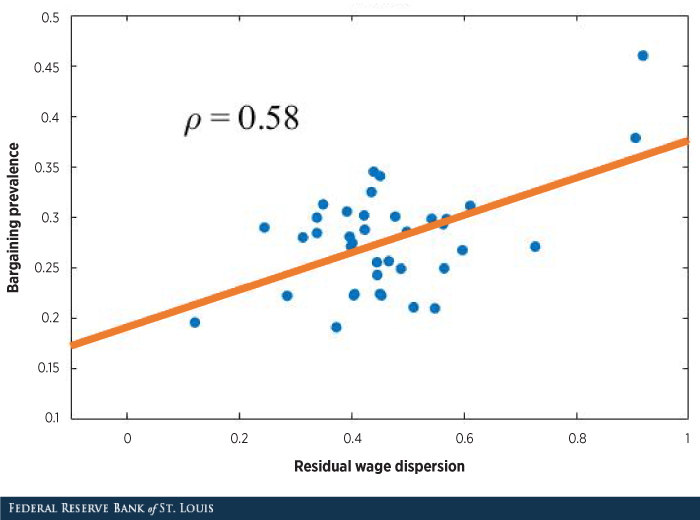

To investigate these questions, we use data from the Survey of Consumer Expectations carried out by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to illustrate the relationship between average wages and bargaining prevalence and the relationship between residual wage dispersion and bargaining prevalence by occupation. Bargaining prevalence refers to the likelihood of an individual negotiating his wage instead of facing a take-it-or-leave-it offer when accepting a job.

Computing Our Measures

Using the main survey as well as its labor market section, containing variables reflecting job search behavior, we pulled data for 2013 through 2017 and calculated the following:

Average Wages

To compute average wages, we took the mean of the logarithmic value of the real wage.

Residual Wage Dispersion

To recover residual wage dispersion, we followed the 2020 work by R. Jason Faberman and others and regressed the logarithmic value of annualized real wages on job characteristics (full-time status, tenure, occupation, firm size, employment benefits, job convenience) and demographic characteristics (race, Hispanic origin, education, gender, age, age squared, marital status, cohabitation status, number of children, homeownership). We used the residuals from the regression to compute the weighted standard deviations of the residual logarithmic value of real wages by occupation.

Note that by using the residuals from the regression in which we control by both job and demographic characteristics, we are identifying that part of an individual’s wage that cannot be explained by observed characteristics. This is what we refer to as “residual wage dispersion.”

Bargaining Prevalence

To construct a measure of bargaining prevalence, we added a set of variables representing measures of search effort to the same regression that we ran to recover residual wages. These variables include the type of work a person is looking for, the number applications that were sent during the job search process, the number of potential employers that contacted the worker, the number of job offers received, and indicators of search methods used.

We believe that the ability of a worker to increase their wage by putting in more effort as well as varying the intensity and method of search reflects the extent to which the wage was bargained, rather than regarded as a take-it-or-leave-it offer. Therefore, we took the fraction of the wage variation jointly explained by these additional variables as a proxy for bargaining prevalence. We rescaled the proxy to cover the unit interval. Similarly to wage dispersion, we computed weighted averages of the bargaining proxy by occupation.The survey contains an explicit question of whether bargaining happened when an offer was extended. However, the overlap between data on wages and on bargaining is very limited; therefore, we could not include this variable in the regression for the proxy or use it as a stand-alone indicator of bargaining.

Relationship between Bargaining Prevalence and Other Measures

The results of the correlation between bargaining prevalence and average wages and residual wage dispersion are depicted in the two figures below. (For more details on average wage, residual wage dispersion and bargaining prevalence by occupation, see the appendix in our related working paper.)

Relationship between Bargaining Prevalence and Residual Wage Dispersion

SOURCE: Survey of Consumer Expectations and authors’ calculations.

Relationship between Bargaining Prevalence and Average Wages by Occupation

SOURCE: Survey of Consumer Expectations and authors’ calculations.

We found that occupations in which workers bargain more have both a higher average wage as well as a higher residual wage dispersion. Both correlations are positive and different from zero at the 0.005 level of significance. The occupations with the higher values of wage dispersion and bargaining represent lawyers and those in construction.

These positive correlations lead us to believe that part of wage inequality can be explained by whether wages are posted or bargained. We explored this question from a theoretical perspective in our working paper.

Notes and References

- The survey contains an explicit question of whether bargaining happened when an offer was extended. However, the overlap between data on wages and on bargaining is very limited; therefore, we could not include this variable in the regression for the proxy or use it as a stand-alone indicator of bargaining.

Additional Resources

- Timely Topics: Wage Posting and Job Searching

- On the Economy: The COVID-19 Recession in Historical Perspective

- On the Economy: The Link between Wages and Switching Careers

- On the Economy: How Quickly Do People Apply for Jobs?

Citation

Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría and Anton Cheremukhin, ldquoDoes Bargaining Help Explain Wage Inequality?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 28, 2021.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions