More Households Face Food Scarcity during COVID-19

Even though the U.S. is well supplied with food, According to 2017 data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the U.S. has the world’s second-highest per capita food supply at 3,766 calories daily. This falls just shy of Belgium, which has a per capita supply of 3,768 calories daily. a nontrivial fraction of U.S. households do not have enough to eat. In 2018, 4.3% of households had very low food security. Households with very low food security are food insecure to the extent that normal eating patterns of some household members were disrupted at times during the year, with self-reported food intake below levels considered adequate, according to a USDA definition.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the issue of food insecurity. In the wake of heavy layoffs and furloughs, a substantial number of households have experienced losses in labor income. Many of these households are low income and already likely to be struggling with having enough to eat.

The new Household Pulse Survey—conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau to evaluate household economic conditions throughout the pandemic—provides timely data on how COVID-19 has affected U.S. households’ access to food, using several questions to assess household situations.

The survey asks respondents to describe the food eaten in their household before March 13, i.e., before the pandemic, and during the last seven days. They answer by choosing from the following responses:

- Enough of the kinds of food wanted to eat

- Enough, but not always the kinds of food wanted to eat

- Sometimes not enough to eat

- Often not enough to eat

We evaluated how the fraction of households experiencing food scarcity has changed from just before the pandemic to the first week of June (May 28–June 2); we measured “food scarcity” by the percentage of survey respondents reporting “sometimes not enough to eat” or “often not enough to eat.” We use the term food scarcity rather than “food insecurity,” as food insecurity is typically defined and assessed using a specific set of questions in the Current Population Survey, and the Household Pulse Survey data are not directly comparable to that definition.

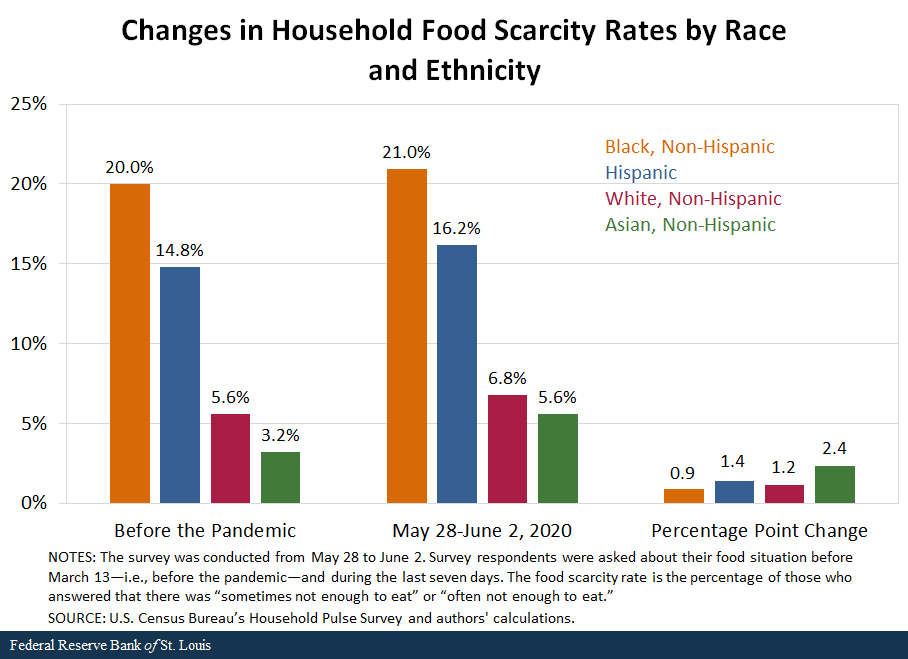

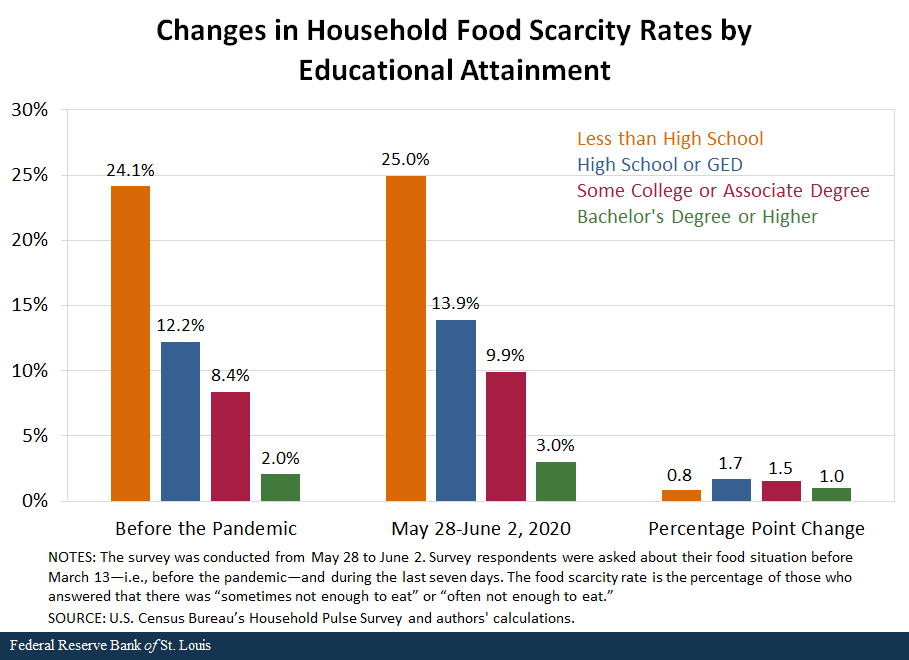

According to the Household Pulse Survey conducted from May 28 to June 2, around 9% of U.S. households experienced food scarcity prior to the pandemic, and around 10.4% of households experienced food scarcity during the first week of June. Food scarcity rates varied considerably according to household characteristics, as shown in the three figures below.

Both before the pandemic and in the first week of June, we observe the highest rates of food scarcity among black households, households whose head has less than a high school degree, and households that earned less than $25,000. Across all demographics, food scarcity rates have increased since the start of the pandemic. We observe the largest increases in food scarcity rates among Asian households, households whose head has only a high school degree or GED equivalent, and households that earned $25,000 to $75,000.

The national increase in households experiencing food scarcity is substantial—around 1.4 percentage points—but perhaps more modest than we would expect, considering the high unemployment numbers and loss of labor income over the past three months. This lower-than-expected increase may be due to stimulus checks and extended unemployment insurance benefits under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act. Average personal income actually rose in April due to federal aid, and this likely helped many households afford to buy food when they otherwise would not have been able to. Additionally, there has been a surge in the use of food bank services during the pandemic, and the support from these organizations may have helped ensure that some households had enough to eat.A recent report (PDF) on the Household Pulse Survey data also suggests that respondents may misremember their households’ food situation from prior to the pandemic, which could affect the magnitude of change in food scarcity that we observe.

During the pandemic, household food scarcity may arise not only due to the loss of income. Of those who reported sometimes or often not having enough to eat in the last seven days, about 80% indicated that they could not afford to buy more food, around 30% indicated that they could not or were afraid to go buy food, and 17% indicated that stores did not have the food they wanted. Respondents were able to select more than one reason for food insufficiency. Many factors—including loss of income, fear of infection and supply chain disruptions—are affecting households’ ability to have enough to eat during the pandemic.

Notes and References

1 According to 2017 data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the U.S. has the world’s second-highest per capita food supply at 3,766 calories daily. This falls just shy of Belgium, which has a per capita supply of 3,768 calories daily.

2 Households with very low food security are food insecure to the extent that normal eating patterns of some household members were disrupted at times during the year, with self-reported food intake below levels considered adequate, according to a USDA definition.

3 A recent report (PDF) on the Household Pulse Survey data also suggests that respondents may misremember their households’ food situation from prior to the pandemic, which could affect the magnitude of change in food scarcity that we observe.

4 Respondents were able to select more than one reason for food insufficiency.

Additional Resources

- St. Louis Fed’s COVID-19 resource page

- On the Economy: Reading the Labor Market in Real Time

- On the Economy: Hot Money Credits to Kick-Start a Stalled Economy?

Citation

YiLi Chien and Julie Bennett, ldquoMore Households Face Food Scarcity during COVID-19,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, June 18, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions