House Hunting in a Period of Social Distancing

The outbreak of COVID-19 has focused much attention on the potential economic effects in the second quarter of 2020 and beyond. As cities and states shut down to quarantine and attempt to mitigate a potential collapse of the health care system, most of the economic discussion has been devoted to evaluating the impact on sectors deemed nonessential.

One of the most important seasonal sectors of the macroeconomy is private residential real estate, which many municipalities have categorized as nonessential. The spring season is often the start of energetic buying and selling activity in private real estate: People relocate from one city to another, homeowners upsize and downsize homes, families move for public schools, and buyers purchase newly constructed houses.

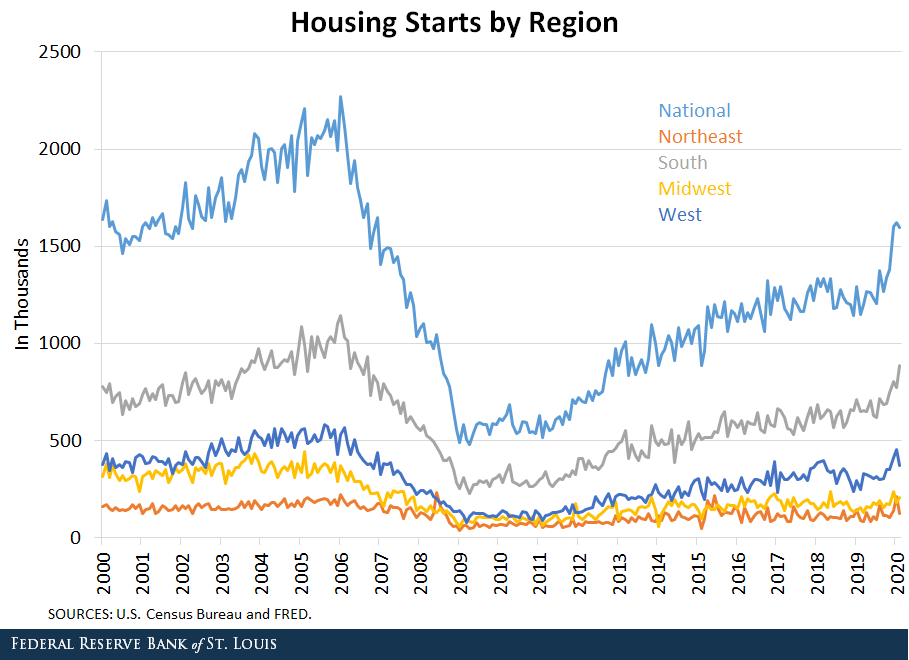

Spring in 2020 officially started March 19; but, due to the widespread global pandemic, the current expectations for prospective buyers and sellers are far from optimistic.Last year, we made a prediction of the future state of the housing market based on the expansion of new construction using the data available until November. The overall message of this research was that the data confirmed the decline in housing permits was occurring throughout much of the country, potentially signaling declining expectations for future housing demand and prices. We predicted the likely result of the continuation of those conditions was some degree of softness in the housing market in 2020. In the past six months, the dynamism of the U.S. economy changed people’s expectations, and the number of housing starts through February increased dramatically, to the highest level seen since before the housing market collapse that started the Great Recession, as seen in the figure below.

This large ramp-up in housing production implies that large quantities of new homes are likely to enter the market starting this spring and continuing through the buying season this summer.

If the COVID-19 pandemic continues for an extended period and financial assistance is not sufficient, some homeowners may be required to sell their homes or be evicted from their homes for missing payments at the same time there is a historic amount of new supply. The federal government has placed a temporary moratorium on evictions and foreclosures for homeowners with mortgages through the Federal Housing Administration, and some individual states are instituting similar protections. But if the economic fallout from COVID-19 continues longer than a few months, more expansive protections may be required.

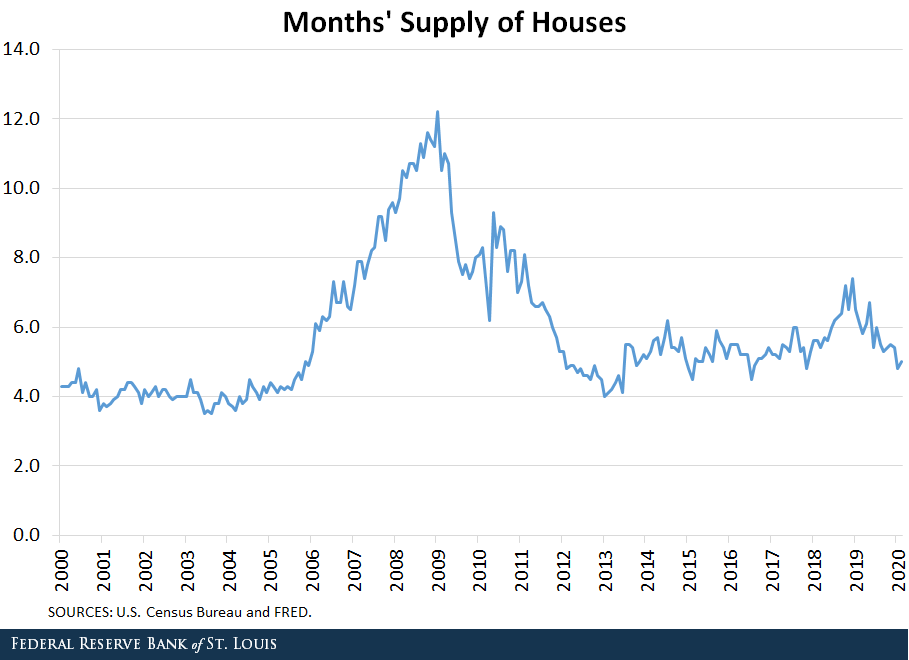

If homeowners need to sell their homes to access liquidity, how quickly can housing units be sold? To measure housing liquidity we use months’ supply, a measure that documents how much inventory is on the housing market given the current number of houses listed and the current pace of houses being sold: A lower number for months’ supply implies quicker times to transact houses. Currently, months’ supply is low from a historical standpoint, as seen in the figure below.

This would imply prospective buyers and sellers take relatively little time to match and transact. However, in times of economic hardship, such as the Great Recession, housing liquidity often adjusts quickly and the market becomes very illiquid.See Famiglietti, Matthew; Garriga, Carlos; and Hedlund, Aaron, “Construction Permits and Future Housing Supply: Implications for 2020,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, Dec. 17, 2019; Garriga, Carlos and Aaron Hedlund, “Mortgage Debt, Consumption, and Illiquid Housing Markets in the Great Recession,” American Economic Review, Forthcoming 2020; and Famiglietti, Matthew, Carlos Garriga, and Aaron Hedlund, “The Geography of Housing Market Liquidity During the Great Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter 2020, Vol. 102, No. 1, pp. 51-78. If the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact economic activity, we expect that the currently liquid housing market will become illiquid rapidly, potentially even before house prices adjust.

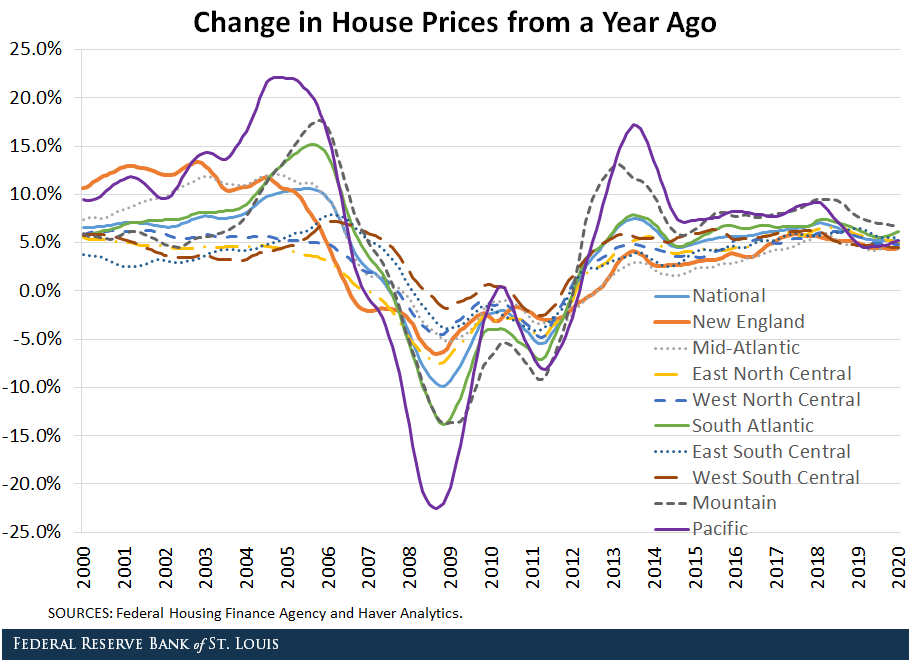

The potential increases in housing supply and liquidity we have documented to this point are likely to be reflected in house prices. The start of spring 2020 shows house price growth slowing from the rate seen in 2018, but growth is still robust at a national average of about 5% on a year-over-year basis, as seen in the figure below.

This slowing in price growth trend appears to be national, but the Pacific, South Atlantic and Mountain regions have been particularly affected. House price levels may even be lowered by weakening demand due to COVID-19. Signs of weakened demand are already visible as a survey by the Mortgage Bankers Association the week of March 25 showed a 29.4% decrease in mortgage applications from the prior week.“Mortgage Applications Decrease in Latest MBA Weekly Survey,” Mortgage Bankers Association, March 25, 2020.

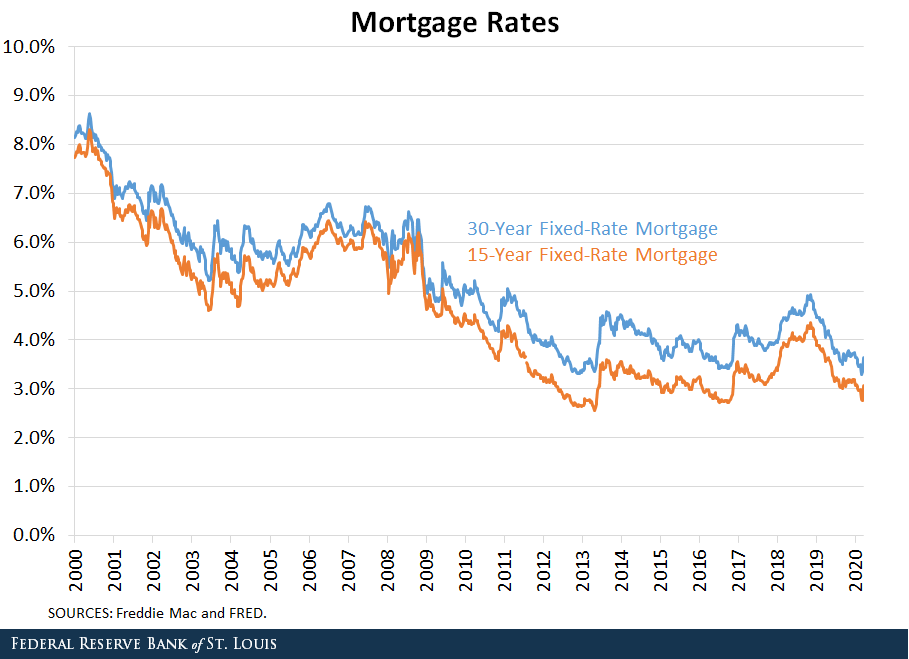

An important determinant for house price levels and growth rates is the cost of financing home purchases. From a buyer’s perspective, the cost of financing is low from a historical perspective, as interest rates sit near their historic lows.

Preemptive cuts to interest rates in 2019 by the Federal Reserve lowered mortgage rates considerably in 2019, and interventions from the Fed guaranteeing purchases of mortgage-backed securities should provide a source of funding.

These recent moves by the Fed should help the housing market, but it is worrying that as of last week, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage increased to 3.65%, a 0.36 percentage point increase since the start of March. This recent spike in mortgage rates would likely have the effect of further slowing or reducing price growth and increasing housing illiquidity. As more data arrive in the coming weeks, it will become evident whether the Fed’s recent actions are enough to stabilize financing costs in the housing market.

Even with action from the Fed to stabilize financing costs, growing uncertainty about stable labor earnings for everyday Americans can lower the desire to purchase a house. This may be especially true as perspective buyers and sellers recall their experiences with the housing market during the Great Recession.

In summary, the lower demand due to quarantine orders, signs of already slowing demand through slowing price growths and mortgage originations, and a historically high supply all hitting the economy at the same time is not likely to deliver the expected start of the spring housing hunting season.

Notes and References

1 Last year, we made a prediction of the future state of the housing market based on the expansion of new construction using the data available until November. The overall message of this research was that the data confirmed the decline in housing permits was occurring throughout much of the country, potentially signaling declining expectations for future housing demand and prices. We predicted the likely result of the continuation of those conditions was some degree of softness in the housing market in 2020.

2 See Famiglietti, Matthew; Garriga, Carlos; and Hedlund, Aaron, “Construction Permits and Future Housing Supply: Implications for 2020,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, Dec. 17, 2019; Garriga, Carlos and Aaron Hedlund, “Mortgage Debt, Consumption, and Illiquid Housing Markets in the Great Recession,” American Economic Review, Forthcoming 2020; and Famiglietti, Matthew, Carlos Garriga, and Aaron Hedlund, “The Geography of Housing Market Liquidity During the Great Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter 2020, Vol. 102, No. 1, pp. 51-78.

3 “Mortgage Applications Decrease in Latest MBA Weekly Survey,” Mortgage Bankers Association, March 25, 2020.

Additional Resources

Citation

Carlos Garriga and Matthew Famiglietti, ldquoHouse Hunting in a Period of Social Distancing,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 1, 2020.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions