Has Australia Really Had a 28-Year Expansion?

In July, the U.S. officially entered its longest expansion on record. Naturally, many are wondering if the expansion is sustainable. When asking this question, many turn to the Australian case, as it has been argued that Australia hasn’t had a recession in 28 years. But is this really the case?

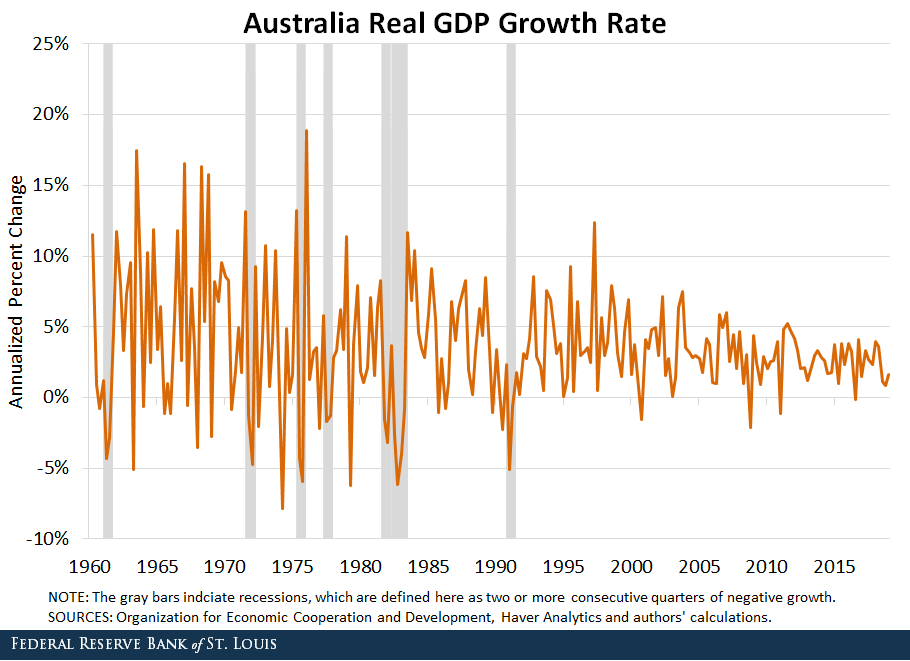

The figure below shows the growth rate of Australia’s GDP, with recessions shaded gray. (Recessions are defined here as two or more consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.)

According to this, Australia has not had a recession since 1991 and has been growing since.

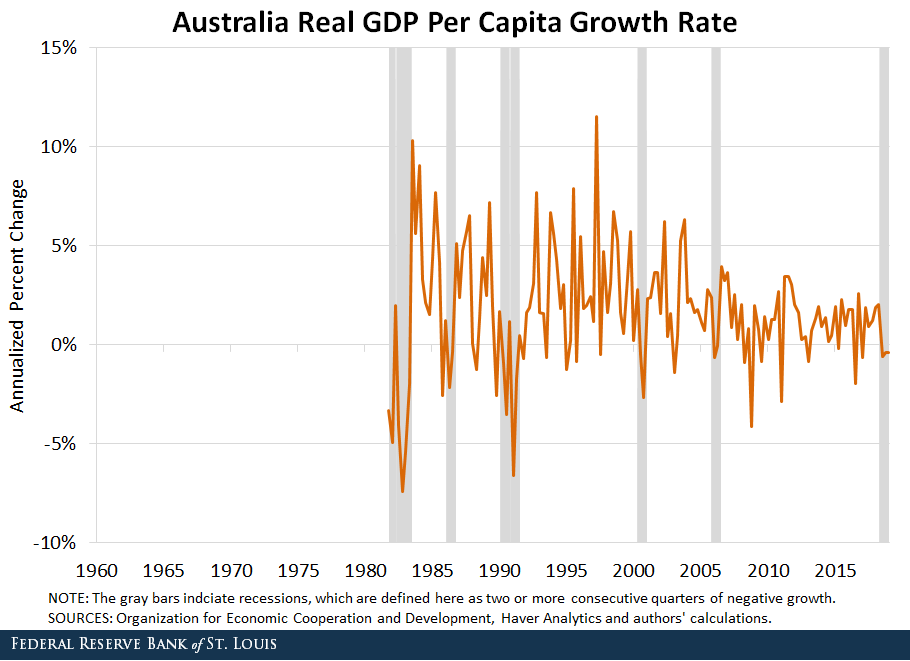

However, when we look at real per capita GDP growth, the story changes. The figure below shows Australia’s per capita GDP growth rate. Again, recessions are shaded gray and defined as two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth.

As shown in the figure, Australia has had three recessions since 1991 when looking at GDP per capita, the most recent one being from the second quarter of 2018 to the first quarter of 2019.

This discrepancy between the growth rate of per capita GDP and the growth rate of GDP implies that population growth has been a key factor for Australia’s economic expansion. A rising population increases the size of the economy, and therefore total output increases, which is reflected in the level of GDP.

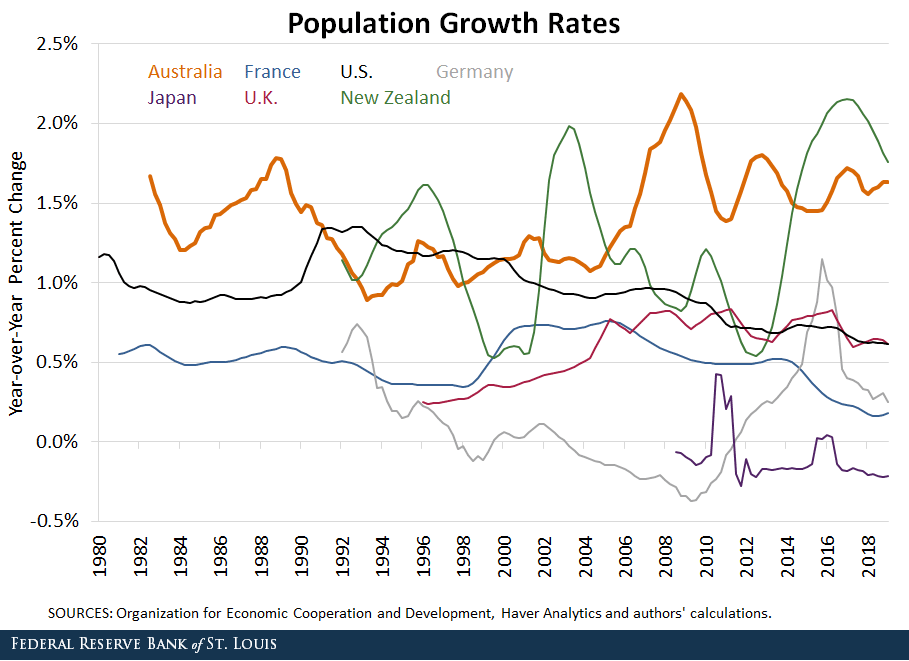

However, the fact that we do see economic downturns in per capita terms means that population is growing faster than GDP. For nearly 40 years, Australia has had a higher population growth rate than other industrialized economies, as seen in the figure below.

In particular, it had a surge in population around 2008—during the height of the global financial crisis—due to migration. This population growth translated to overall positive GDP growth, but its effect on GDP growth hasn’t been enough to prevent recessions in per capita terms. Per capita recessions are not unique to Australia. In the table below, we compare the number of observed recessions when using GDP growth versus per capita GDP growth for several OECD countries. Again, a recession is defined as two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth.

| Real GDP | Per Capita Real GDP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Sample Range | Episodes | Average Duration (Quarters) | Episodes | Average Duration (Quarters) | ||

| Australia | 1981Q3 - 2019Q1 | 3 | 2.7 | 8 | 2.4 | ||

| France | 1980Q1 - 2019Q1 | 3 | 3.3 | 6 | 3.3 | ||

| Germany | 1991Q1 - 2019Q1 | 6 | 2.7 | 7 | 2.7 | ||

| Japan | 2007Q3 - 2019Q1 | 4 | 2.8 | 4 | 2.8 | ||

| New Zealand | 1991Q1 - 2019Q1 | 4 | 3.0 | 5 | 3.2 | ||

| United Kingdom | 1995Q1 - 2019Q1 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 6.0 | ||

| United States | 1947Q1 - 2019Q2 | 10 | 2.4 | 15 | 2.6 | ||

| Overall | 31 | 2.8 | 46 | 2.8 | |||

| NOTES: We define a recession as two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth. The sample range corresponds to where there is overlap between quarterly real GDP and population. | |||||||

| SOURCES: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Haver Analytics and authors’ calculations. | |||||||

We found that most of these countries had more recessions when we looked at per capita GDP growth versus just GDP growth. This means that GDP is growing but oftentimes not fast enough to compensate for population growth. For example, although the U.S. has not had a recession since 2009, when we look at per capita GDP growth, the U.S. fell into a brief recession at the end of 2012.

So should we use Australia as a benchmark when thinking about possible duration of expansions? If so, we have to take it with a grain of salt because looking at just GDP growth doesn’t paint the whole picture. It is important to look at per capita GDP growth to have a broader view.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: What Causes a Country’s Standard of Living to Rise?

- On the Economy: The Exports of Innovative Countries

- On the Economy: How Do the Hours Americans Work Compare to the Rest of the World?

Citation

Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría and Brian Reinbold, ldquoHas Australia Really Had a 28-Year Expansion?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Sept. 26, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions