Syndicated Loans in the U.S.

A syndicated loan is a loan issued to a single borrower by a group of lenders (known as a syndicate). The task of finding additional lenders falls to a lead bank rather than a firm, so it is often easier for a firm requiring a large loan to turn to syndicated lending. It is beneficial for lenders as well, since they can lend to larger borrowers Syndicated loans are usually large enough that regulation would prevent a single lender from undertaking them by itself. and are less exposed to the risk of borrower default by spreading the risk among multiple lenders. In this post, we describe recent trends in the domestic holdings of syndicated loans.

Syndicated Loan Volume

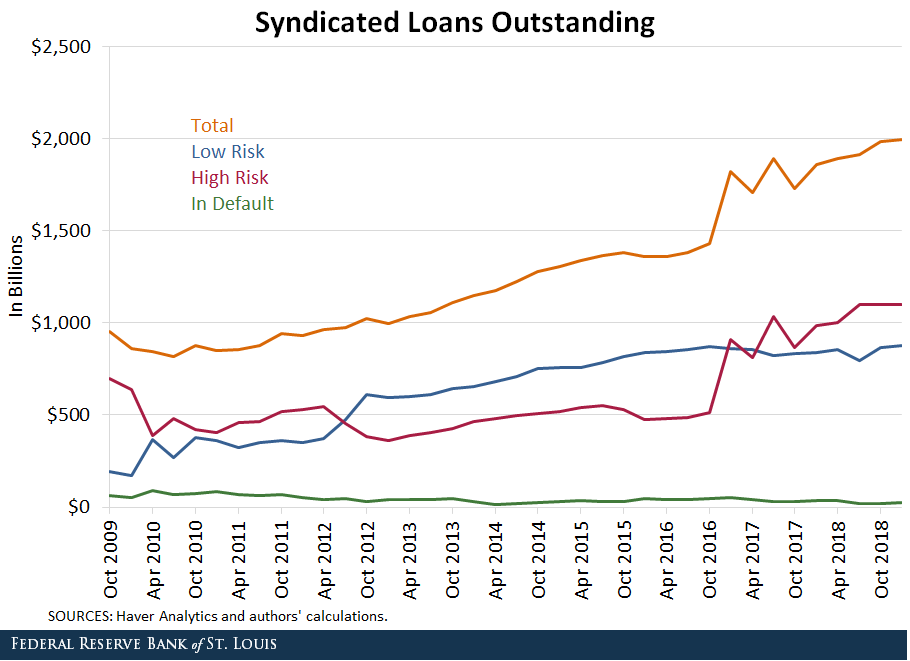

Syndicated loans have risen dramatically over the past several years, with the volume of syndicated loan origination exceeding that of other popular types of credit (such as corporate bonds) as of 2018. The figure below plots the size of domestically held syndicated loan portfolios based on default risk. Default risk, in this case, is calculated as the two-year probability of default provided by the reporting financial institution: If this probability is above 1% (or missing), we classified them as high risk. Otherwise, we classified them as low risk.See the Federal Reserve Board’s “Syndicated Loan Portfolios of Financial Institutions.”

From the graph, we can see that the amount outstanding on high-risk syndicated loans has grown rapidly in the last couple of years. In the first quarter of 2019, it was more than $1 trillion and about 55% of all syndicated loans.

Who Holds Syndicated Loans?

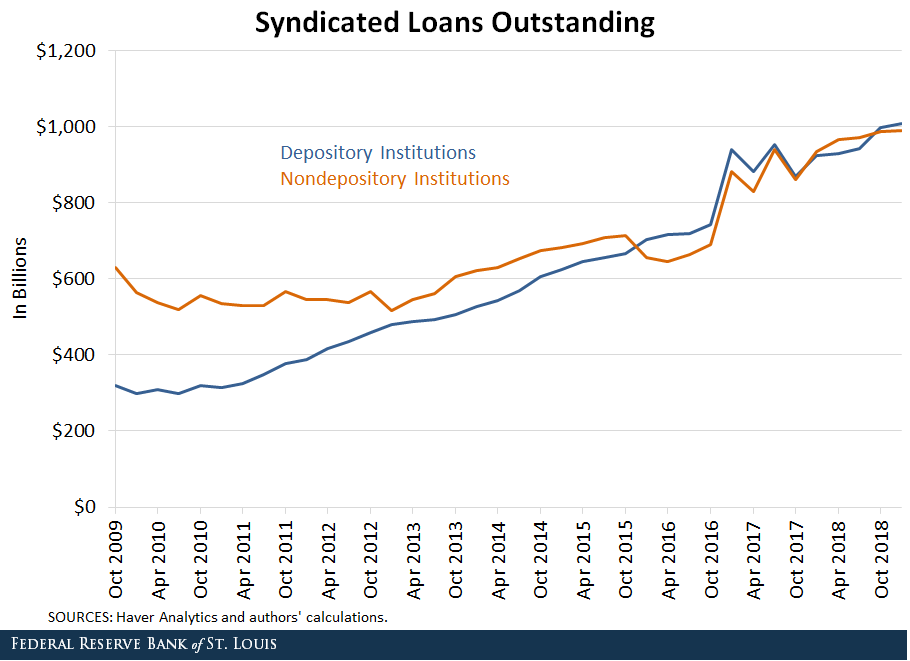

A wide range of institutions can hold syndicated loans. These institutions can be broadly classified into depository institutions—such as financial holding companies, national banks and credit unions—and nondepository institutions—which includes all other financial institutions, such as hedge funds.

The figure below shows the amount outstanding on syndicated loans held by these two types of institutions.

It is interesting to note that while nondepository institutions initially held a larger share of syndicated loans in their portfolios, depository institutions seem to have caught up over the last few years. Now, they both seem to hold a somewhat even share of syndicated loans. In the first quarter of 2019, the amount outstanding on syndicated loans held by depository institutions was a little over $1 trillion, while that held by nondepository institutions was slightly under $1 trillion ($990 billion).

Risky Syndicated Loans

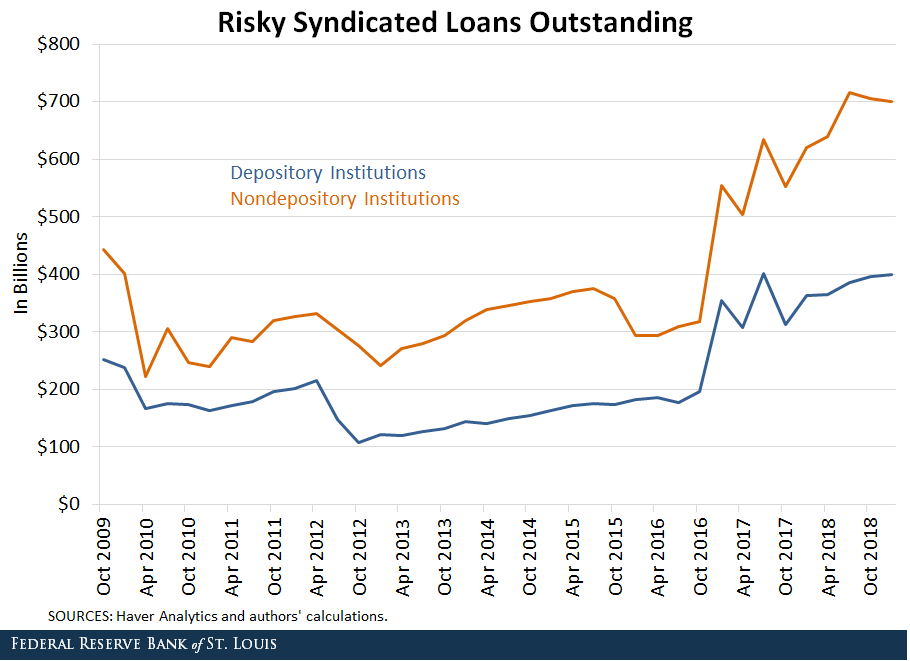

This trend, however, is quite different when we focus purely on high-risk syndicated loans, defined as loans with a two-year default probability above 1%. The graph below shows us that nondepository institutions seem to be holding a significantly larger share of risky syndicated loans compared to depository institutions.

In the first quarter of 2019, loan holdings of depository institutions were around $400 billion, while those of nondepository institutions were around $700 billion.

To conclude, a majority of corporate debt issuance occurs in the form of syndicated loans, and domestic holdings of high-risk syndicated loans have increased very rapidly relative to low-risk loans over the last few years, particularly among nondepository institutions.

It is also worth noting that this blog post focuses on directly held syndicated loans. Financial institutions can also be indirectly exposed to this type of credit instrument via securities such as collateralized loan obligations. For an analysis of domestic holdings of collateralized loan obligations, see Liu, Emily; and Schmidt-Eisenlohr, Tim. “Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?”, FEDS Notes, July 19, 2019. For this reason, actual exposures can in fact be much larger than what we show here.

Notes and References

1 Syndicated loans are usually large enough that regulation would prevent a single lender from undertaking them by itself.

2 See the Federal Reserve Board’s “Syndicated Loan Portfolios of Financial Institutions.”

3 For an analysis of domestic holdings of collateralized loan obligations, see Liu, Emily; and Schmidt-Eisenlohr, Tim. “Who Owns U.S. CLO Securities?”, FEDS Notes, July 19, 2019.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Corporate Debt Since the Great Recession

- On the Economy: Can Corporate Social Responsibility Be Profitable?

Citation

Miguel Faria-e-Castro and Asha Bharadwaj, ldquoSyndicated Loans in the U.S.,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Oct. 8, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions