Financial Contagion: Lessons from the Great Depression

The financial crisis of 2008-09 sparked interest in how relationships within the financial system can amplify shocks. Although financial contagion can occur in various ways, explicit contractual ties between firms are widely thought to have been an important source of contagion in the recent crisis and in many crises historically.

Contractual linkages among large financial institutions were a foremost concern of policymakers in the recent crisis. For example, the Federal Reserve provided a loan to American International Group (AIG) when it was on the verge of failing and unable to obtain funding from other sources. Then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke explained that AIG’s extensive contractual ties were a key reason the Fed stepped in: “AIG was counterparty to many of the world’s largest financial firms, a significant borrower in the commercial paper market and other public debt markets, and a provider of insurance products to tens of millions of customers.”Bernanke, Ben S. “Reflections on a Year of Crisis.” Remarks at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Annual Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyo., Aug. 21, 2009. For additional details, see Bernanke, Ben S. The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and its Aftermath, Chapter 13. New York: W.W. Norton, 2015.

Banks and other financial firms have contractual exposures to one another through a variety of channels, including:

- Interbank loans and deposits

- Commercial loan participations

- Derivative contracts

Studying Interbank Connections

Many of these connections are complex or opaque, however, which makes studying how contractual relationships can lead to contagion difficult. Two new studies I co-authored provide insights about how contractual ties between banks can amplify financial distress by looking back to the early 20th century, when links between banks were less complex and largely observable.

At that time, contractual ties between banks consisted mainly of correspondent relationships. Most banks maintained deposits in other banks (their “correspondents”) for:

- Making payments in distant locations

- Investing surplus funds, especially in seasons when the local demand for loans was low

- Satisfying legal reserve requirements

Banks would draw down their correspondent deposits when local demands rose and sometimes borrow funds from their correspondents to meet extraordinary demands. Published directories identified the principal correspondents of every bank.

The universe of correspondent relationships among banks formed an interbank network that had a “core-periphery” structure, with large banks in New York City at the core of a system comprised of local, regional and super-regional nodes connecting banks across the country.

My paper “The Founding of the Federal Reserve, the Great Depression and the Evolution of the U.S. Interbank Network,” co-authored with Utah State University professor Matthew Jaremski, used newly digitized information on the universe of correspondent connections to examine how two key events—the Fed’s 1914 opening and the Great Depression—caused the U.S. interbank network to evolve.Jaremski, Matthew; and Wheelock, David C. “The Founding of the Federal Reserve, the Great Depression and the Evolution of the U.S. Interbank Network.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-002B, June 2019. In particular, we investigated how these events affected overall network concentration and the distribution of network connections among banks and cities with different characteristics.

Banking Structure in the Early 20th Century

Our research confirmed that the interbank network at the beginning of the 20th century was pyramidal in structure, with a small number of banks serving as correspondents for a high percentage of the nation’s banks. Nearly every bank deposited funds in at least one other bank, yet very few banks held funds for other banks.

Further, we showed that the Fed’s founding led to a decline in network concentration: Banks shifted their correspondent relationships away from New York City toward banks in other cities, especially those with Fed offices within their Fed district. The Great Depression further focused the network on Fed cities as banks increasingly favored Fed-member banks—which had lower failure rates and could provide their customers with access to Fed liquidity—as their correspondents.

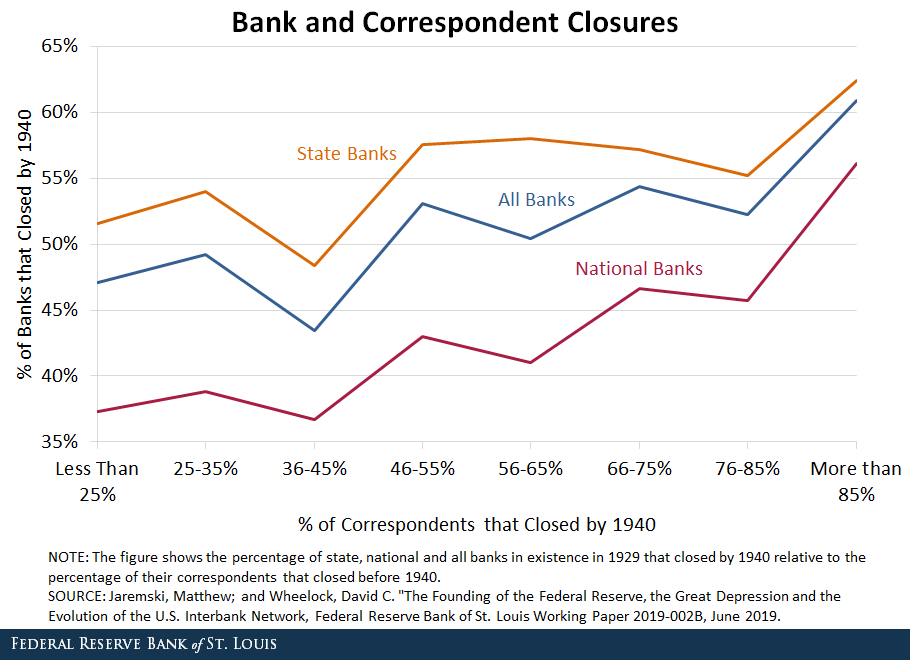

The Great Depression showed the importance of connecting to strong correspondents. A bank might lose access (at least temporarily) to funds it had on deposit in a correspondent that failed, which could impair its own condition. As the chart below shows, closure rates were higher among banks with higher rates of closure among their correspondents.Our data revealed whether or not a bank closed, but not whether the closure was due to failure, voluntary liquidation or merger with another bank. However, during the Depression, the vast majority of all of these events reflected financial distress.

For example, more than 55% of national banks (i.e., banks with a federal charter) closed among those with a correspondent closure rate of 85% or higher. On the other hand, fewer than 40% of national banks closed among those with a correspondent closure rate of 45% or less. Closure rates were uniformly higher for state-chartered banks, but the positive relationship between bank and correspondent closure rates was similar.

Interbank Connections and Financial Distress

In another paper I co-authored with Jarmeski and Columbia University professor Charles Calomiris, we examined the relationships between interbank connections and financial distress more formally using regression analysis.Calomiris, Charles W.; Jaremski, Matthew; and Wheelock, David C. “Interbank Connections, Contagion and Bank Distress in the Great Depression.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-001D, September 2019. Controlling for various aspects of a bank’s balance sheet—such as its size, capital and loan ratios—as well as local market conditions, we confirmed that banks were more likely to close when a higher percentage of their correspondents closed.

We also found that correspondent banks were more likely to close when a higher percentage of their respondents closed.Respondents are the banks that hold deposits in a given correspondent bank. Those deposits are an asset of the respondent and a liability of the correspondent. When a respondent closed, the correspondent would lose a source of funds, likely permanently. During the Great Depression, when many banks were closing, losing interbank deposits could significantly reduce a correspondent bank’s access to funds. Thus, we found that the interbank system was a source of risk that transmitted financial distress in two directions: from banks to their correspondents, as well as from correspondents to their respondents.

The evidence makes clear that interbank connections were an important source of contagion in the Great Depression and can pose significant liquidity risk in a crisis.

Notes and References

1 Bernanke, Ben S. “Reflections on a Year of Crisis.” Remarks at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Annual Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyo., Aug. 21, 2009. For additional details, see Bernanke, Ben S. The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and its Aftermath, Chapter 13. New York: W.W. Norton, 2015.

2 Jaremski, Matthew; and Wheelock, David C. “The Founding of the Federal Reserve, the Great Depression and the Evolution of the U.S. Interbank Network.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-002B, June 2019.

3 Our data revealed whether or not a bank closed, but not whether the closure was due to failure, voluntary liquidation or merger with another bank. However, during the Depression, the vast majority of all of these events reflected financial distress.

4 Calomiris, Charles W.; Jaremski, Matthew; and Wheelock, David C. “Interbank Connections, Contagion and Bank Distress in the Great Depression.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2019-001D, September 2019.

5 Respondents are the banks that hold deposits in a given correspondent bank. Those deposits are an asset of the respondent and a liability of the correspondent.

Additional Resources

Citation

David C. Wheelock, ldquoFinancial Contagion: Lessons from the Great Depression,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 11, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions