Taking a Closer Look at Residual Seasonality and U.S. GDP Growth

Getty/Nuthawut Somsuk

Getty/Nuthawut Somsuk

In past decades, first-quarter economic growth has been substantially lower than the growth in other quarters, even after adjusting for typical seasonality. Economists have called this phenomenon “residual seasonality,” and a recent article in the Regional Economist explored this issue.

St. Louis Fed Economist Michael T. Owyang and Senior Research Associate Hannah G. Shell looked at this trend of growth being weaker in the first quarter than in other quarters.

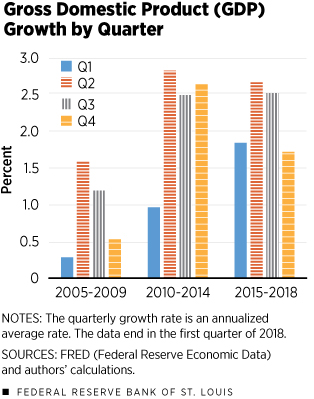

They compared quarterly growth rates of gross domestic product (GDP) during three periods (2005-09, 2010-14 and 2015-18). As the figure below shows, annualized average GDP growth is markedly lower in the first quarter, according to the authors.

Residual seasonality is based on the idea that “the published first-quarter GDP growth rate is artificially low and that actual growth is more in line with that of the other quarters,” Owyang and Shell wrote.

The phenomenon has been recognized by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the U.S. agency that compiles GDP data. The BEA made efforts to correct it in its comprehensive GDP revisions released in 2018, the authors noted.

This phenomenon creates a problem for forecasters and policymakers trying to make timely evaluations of the economy. Residual seasonality can make it difficult to know whether weak first-quarter growth reflects actual conditions or is an understated number. This could affect policy actions, the authors said.

What Are Seasonality and Residual Seasonality?

Economic data have predictable variations throughout the year, caused by such things as summer vacations, holidays, the seasonal nature of production (e.g., agriculture) and weather.Seasonal adjustment wouldn’t remove unusually severe weather events, such as hurricanes or blizzards, since these are not predictable and do not occur every year.

In order to compare growth across consecutive quarters, economists usually remove this predictable variation—called “seasonality”—from the data.

“Residual seasonality, like seasonality in general, is a predictable pattern of output that occurs over the year, but current methods are failing to measure it,” the authors wrote. “Thus, residual seasonality is not removed in the initial seasonal adjustment process.”

Why might residual seasonality exist? Some economists have identified the same residual seasonal patterns in the nonresidential structures, government consumption and exports components of GDP. The authors observed that this supports the idea that small seasonalities unaccounted for in the GDP components could be producing noticeable seasonal patterns in the aggregate.

What Does It Matter for Policymaking?

Residual seasonality can create additional uncertainty for policymakers, Owyang and Shell wrote. For example, low first-quarter data could impact the level of interest rates in the case of the Taylor rule, which suggests an appropriate interest rate based on inflation and the actual level of GDP relative to potential GDP.

“If first-quarter GDP were reported as 1 percent lower than the actual value due to residual seasonality, the output gap would widen, which could mean dropping (interest) rates by 0.5 percentage point under the Taylor rule,” they wrote. “But policymakers, aware of residual seasonality, wouldn’t react, thus keeping rates higher than recommended by the Taylor rule.”

So, how could policymakers get a better sense of actual economic activity? The authors said policymakers could look at additional indicators of aggregate activity that aren’t subject to the same magnitude of residual seasonality.

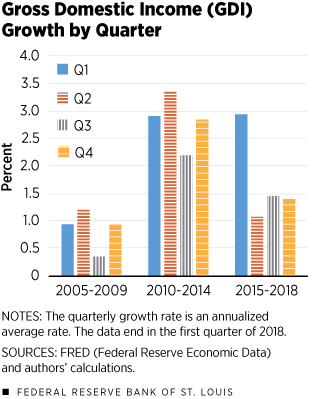

“The BEA tested both GDP and gross domestic income (GDI) for residual seasonality and found that while GDP does exhibit residual seasonality, GDI does not,” the authors noted.

GDI measures economic activity in terms of income earned, while GDP measures it in terms of production. The two are theoretically equivalent, but they differ slightly in practice due to differences in source data, they added.

The figure below plots GDI by quarter for the same periods as shown in the figure above.

“During the first two periods, first-quarter GDI growth is only slightly lower than second-quarter GDI growth and is much higher than first-quarter GDP growth in the same periods,” they wrote. “During the last period, GDI growth is actually higher in the first quarter than the other quarters.”

Looking at GDI growth in addition to GDP growth provides policymakers with additional data on economic activity, the authors concluded.

“If the policymaker observes a relatively low first-quarter GDP number and a GDI number that is more in line with expectations, it is likely that the GDP number is understated because of residual seasonality,” they wrote. “By observing GDI along with GDP, the policymaker can make a more informed decision regarding policy rates.”

Notes and References

1 Seasonal adjustment wouldn’t remove unusually severe weather events, such as hurricanes or blizzards, since these are not predictable and do not occur every year.

Additional Resources

- Regional Economist: Dealing with the Leftovers: Residual Seasonality in GDP

- Economic Synopses: Measuring Potential Output

- On the Economy: GDP, Labor Force Participation and Economic Growth

Citation

ldquoTaking a Closer Look at Residual Seasonality and U.S. GDP Growth,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Jan. 1, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions