A Primer on Negative Interest Rates

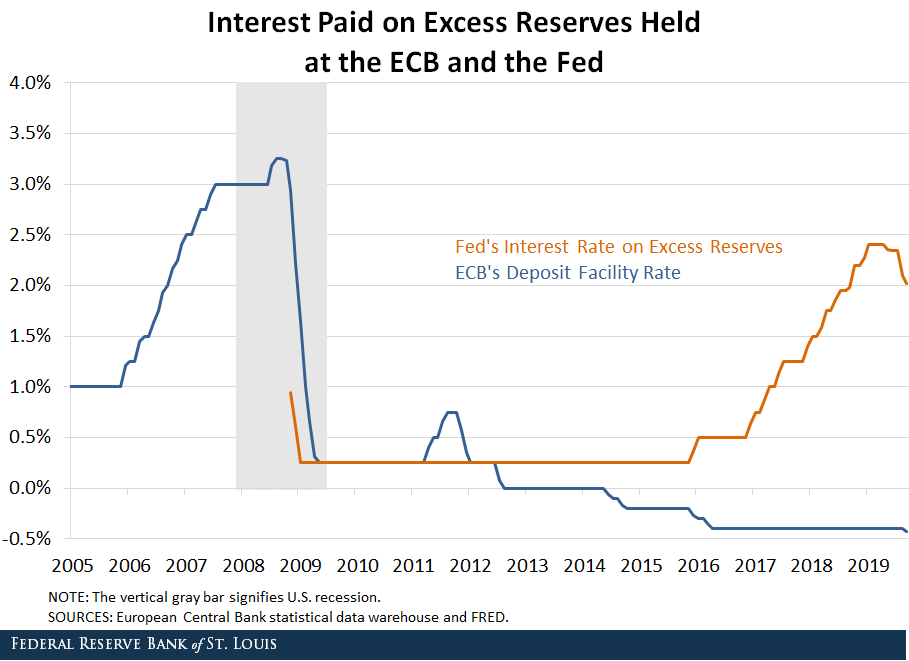

The European Central Bank (ECB) in recent months cut its key deposit facility rate—or the interest rate that European banks earn when they deposit excess reserves at the ECB—to negative 0.5% with the intent of stimulating growth. The figure below presents this rate alongside the deposit rate U.S. banks earn at the Federal Reserve. In the U.S., this rate is referred to as the IOER (interest on excess reserves) rate.

As can be seen, negative interest rates were first introduced by the ECB in June 2014. The Fed has not followed a negative interest rate policy, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell has stated that a forward guidance policy and large-scale asset purchases would be preferred.Powell, Jerome. “Transcript of Chair Powell’s Press Conference.” Federal Open Market Committee, Sept. 18, 2019. In this blog post, we examine the idea behind a negative interest rate policy as well as what could result.

Lowering Interest Rates

Influencing interest rates is an important piece of modern monetary policy. If the economy is slowing, then the conventional response is to lower interest rates, which in turn has two primary effects:

- Consumption and investment spending increase because the cost of borrowing is lower.

- People saving their money in “safe” places (like deposits at a bank) earn a lower rate of interest and are incentivized to either save less or invest their money in riskier assets that offer higher expected returns. Both of these options would again spur consumption and investment.

However, convention further dictates that there is a “zero lower bound” on how much the economy can be stimulated in this way. In other words, nominal interest rates cannot go below zero. Otherwise, borrowers would get paid to borrow money!

Negative Interest Rates

Negative interest rate policies, however, suggest that this idea is not as crazy as it sounds and that interest rates can indeed go below zero. (To be clear, the interest rate we are talking about here is the rate that banks will be paid on their excess reserves at the central bank, which can be thought of as the funds that banks are not using anywhere else.)

With a negative interest rate, the central bank is essentially telling private banks “use it or lose (some of) it.” The aforementioned rate of negative 0.5% means that any bank holding excess reserves at the ECB will lose 0.5% of those funds over the course of a year.

Would Consumers Receive Interest to Borrow?

Note that, although possible,Jyske Bank in Denmark was the world’s first to offer these sorts of negative interest rates on mortgages. this does not necessarily mean that loans to individual consumers would receive a negative interest rate. All banks have to do to avoid charges from the central bank is use the money they would have held in excess elsewhere.Christopher Waller pointed out that negative interest rates are like a tax on banks in a May 2016 blog post.

Given that most consumers and businesses who want loans at current interest rates have already taken them, however, the bank will only be able to attract borrowers for these new funds if they lower their interest rates. Thus, while negative rates for banks do not always translate into negative rates for borrowers, they do produce lower interest rates for borrowers than would have been possible if the central bank had not crossed the “zero lower bound.”

Potential Consequences of Negative Interest Rates

Being a relatively new monetary policy tool, negative interest rates are controversial due to both their known and unknown potential consequences.To mitigate the differential effects from such a policy, the ECB instituted a tiered system where a portion of bank deposits is exempted from the charge. If reserves do not exceed six times banks’ mandatory reserves, then the banks would not have to pay the charge.

If negative deposit interest rates result in lower interest rates faced by households and businesses, an initial reaction may be that this is a generally favorable policy. However, people will be affected by rate cuts in different ways.

For example, if negative interest rates impact mortgage rates, spending on housing may increase. The lessons learned from before the Great Recession—when easy mortgage borrowing contributed to a massive build-up and subsequent fall in home values—must be kept in mind. Some households purchased homes only to eventually learn that they could not afford the mortgage payment. This effect carries over to other forms of household debt.

Savers are also impacted. Households in retirement or preparing to enter retirement tend to prefer safer investments, and, as discussed previously, a negative interest rate policy makes safe investments much less attractive, resulting in moves toward riskier investments.

For firms, the underlying idea is that firms will take advantage of this opportunity and increase investment spending if interest rates are lower. If highly productive investment alternatives exist and await funding, these investments can enhance productivity and growth. However, if awaiting investment opportunities have lower expected returns or greater risk, the long-term benefits are minimalized. An underlying premise is that the existing allocation of resources can be made more efficient, and this may or may not be accurate.

Notes and References

1 Powell, Jerome. “Transcript of Chair Powell’s Press Conference.” Federal Open Market Committee, Sept. 18, 2019.

2 Jyske Bank in Denmark was the world’s first to offer these sorts of negative interest rates on mortgages.

3 Christopher Waller pointed out that negative interest rates are like a tax on banks in a May 2016 blog post.

4 To mitigate the differential effects from such a policy, the ECB instituted a tiered system where a portion of bank deposits is exempted from the charge. If reserves do not exceed six times banks’ mandatory reserves, then the banks would not have to pay the charge.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Negative Interest Rates: A Tax in Sheep’s Clothing

- Regional Economist: Looking for the Positives in Negative Interest Rates

- Regional Economist: How Low Can You Go? Negative Interest Rates and Investors’ Flight to Safety

Citation

Don Schlagenhauf and Ryan Mather, ldquoA Primer on Negative Interest Rates,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Dec. 16, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions