How Might Spring Flooding Affect Real GDP?

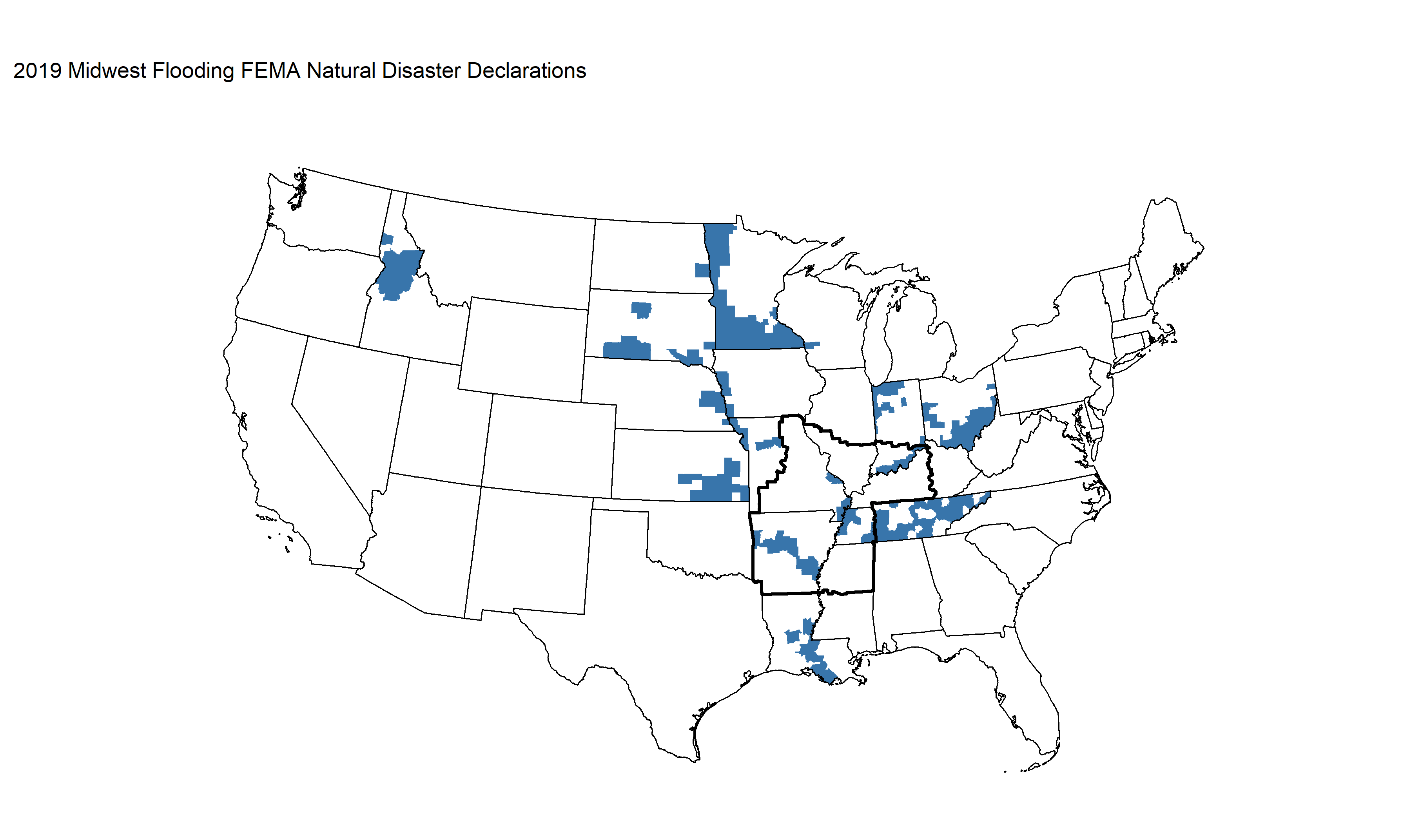

This spring, a significant portion of the U.S. experienced devastating flooding. As many as 7.9% of U.S. counties received natural disaster declarations by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. These counties account for about 4% of the U.S. population, although in many cases major portions of these counties were not affected by the flooding.

While damages are still being assessed, preliminary estimates suggest that total damages could exceed $10 billion. As of Aug. 1, total damages from flooding are estimated around $6 billion with half of states reporting. An early estimate from accuweather.com estimated damages at $12.5 billion.

While the flooding is devastating to households and businesses involved, the overall economic effect of disasters can be slight as some losses are insured and recovery efforts and rebuilding could increase economic activity.For a discussion of the economics of natural disasters, see our 2017 Dialogue with the Fed with Kevin Kliesen, “The Economic Impact of Natural Disasters

Flooding’s Effect on Crops

In cases of flooding, the impact on real GDP is likely to come from the effect of the flooding (and generally wet weather) on the agricultural sector.Depending on the size of the flooding, some firms could face increased transportation costs or production delays due to road, rail or river closures. However, these effects are difficult to quantify. Wet weather this spring significantly delayed or reduced the planting of crops like corn and soybeans, and maturation of these and many other crops is well behind 2018 levels.

For example, as of July 21, only 35% of corn was silking (78% in 2018) and 40% of soybeans were blooming (76% in 2018). As a consequence, the Department of Agriculture has steadily marked down its estimates of total U.S. farm production for this growing season since its first report in February.

The U.S. agricultural sector feeds into total GDP in many different lines (such as production of food). However, the most notable effect of a delayed or lower harvest is on U.S. farm inventories, which is a component of gross private domestic investment.Change in private inventories is the sum of farm and nonfarm inventories.

The Floods of 1993

The 2019 floods have stirred references to the great Mississippi River floods of 1993, most notably in an earlier blog post by our colleagues Kevin Kliesen and Kathryn Bokun. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated that damage from the 1993 floods totaled $37.7 billion dollars (in 2019 prices), about three times as high as estimates of the current floods.

Looking into the FRASER economic archives, we see that the 1993 floods were also at the top of the minds of Federal Reserve policymakers during the Federal Open Market Committee meeting on Aug. 17, 1993. Here are a few excerpts related to the flood from that meeting:

Chicago Fed President Silas Keehn

“...it is still, of course, premature to judge the full economic impact of the flood. But in a broader perspective, I don’t think the effect will be nearly as large as one might guess by watching the television coverage on it.”

Kansas City Fed President Thomas Hoenig

“The effect of the flooding is likely to reduce crop output in our area…. On the whole, prospects in agriculture should remain healthy despite this reduction in crops because of price effects.”

St. Louis Fed President Thomas Melzer

“…for those who are directly affected it’s very devastating…. I think the assessment that the broad economic impact is going to be relatively narrow is on target.”

Economic Projections in 1993

The Fed staff forecasts reported in the August Greenbook (which contains projections about how the economy will fare in the future) indicated that flood disruptions likely delayed residential investment and impacted some shipments of goods, while disaster relief and rebuilding had the potential to boost growth. Staff at the time reported the primary impact on real GDP would act “mainly as a negative swing in farm inventory investment in the second half of 1993.”

By the Nov. 16, 1993, meeting, staff had additional information on the fall harvest and reported estimates of the delayed planting and crop losses in the Greenbook. The staff estimated that:

- Third-quarter real GDP growth would be 0.6 percentage points slower due to crop losses and a delayed harvest.

- Fourth-quarter real GDP growth would be 0.4 percentage points faster as delayed harvest pushed some output that would normally occur in the third quarter into the fourth quarter.

- The overall effect of the flooding on GDP in 1993 was to reduce total output growth by 0.2 percentage points.For the record, the staff forecast for Q3:1993 real GDP growth was correct at 2.8%. The fourth-quarter number surprised to the upside at 5.9%.

| 1993 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Q3 | Q4 | 1993 | 1994 | |

| Real GDP | 1.3 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

| Previous | 1.3 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| Excluding crop losses | 3.4 | 3.6 | |||

| Previous | 1.8 | 3.0 | |||

| Civilian unemployment rate1 | 7.0 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.7 |

| Previous | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| CPI inflation | 3.3 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

| Previous | 3.3 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| 1Averages for final quarter of period shown. | |||||

| SOURCE: Federal Open Market Committee. Retrieved from FRASER. | |||||

Lessons Learned from 1993

The experience of the 1993 floods and how the Fed policymakers measured the impact of crop losses on real GDP provides a useful context for understanding how this year’s flooding could affect real GDP growth over the second half of 2019.

First, by most estimates, the 2019 floods were not as severe as the 1993 floods. Thus, it seems reasonable to expect that the overall impact on output growth is likely to be less than the 0.2 percentage points estimated in 1993.

Second, the impact of the flooding on real GDP growth will likely occur through changes in farm inventories, which depend on this year’s harvest. While USDA forecasts for 2019 production have been marked down, the weather is usually too unpredictable to confidently predict crop yields until this fall.

Third and most importantly, while the overall impact may be small, a delayed harvest due to late planting or slow crop maturation could lead to a notable decline in third-quarter real GDP followed by a similarly sized uptick in the fourth quarter.

Notes and References

1 For a discussion of the economics of natural disasters, see our 2017 Dialogue with the Fed with Kevin Kliesen, “The Economic Impact of Natural Disasters.”

2 Depending on the size of the flooding, some firms could face increased transportation costs or production delays due to road, rail or river closures. However, these effects are difficult to quantify.

3 Change in private inventories is the sum of farm and nonfarm inventories.

4 For the record, the staff forecast for Q3:1993 real GDP growth was correct at 2.8%. The fourth-quarter number surprised to the upside at 5.9%.

Additional Resources

- Dialogue with the Fed: The Economic Impact of Natural Disasters

- On the Economy: Crop Prices and Flooding: Will 2019 Be a Repeat of 1993?

- On the Economy: Economic Effects: Hurricane Harvey vs. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita

Citation

Charles S. Gascon, ldquoHow Might Spring Flooding Affect Real GDP?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 15, 2019.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions