Housing Recoveries without Homeowners: A Global Perspective

In the aftermath of WWII, several developed economies (such as the U.K. and the U.S.) had large housing booms fueled by significant increases in the homeownership rate. The length and the magnitude of the ownership boom varied by country, but many of these countries went from a nation of renters to a nation of owners by around the late 1970s to mid-1980s.

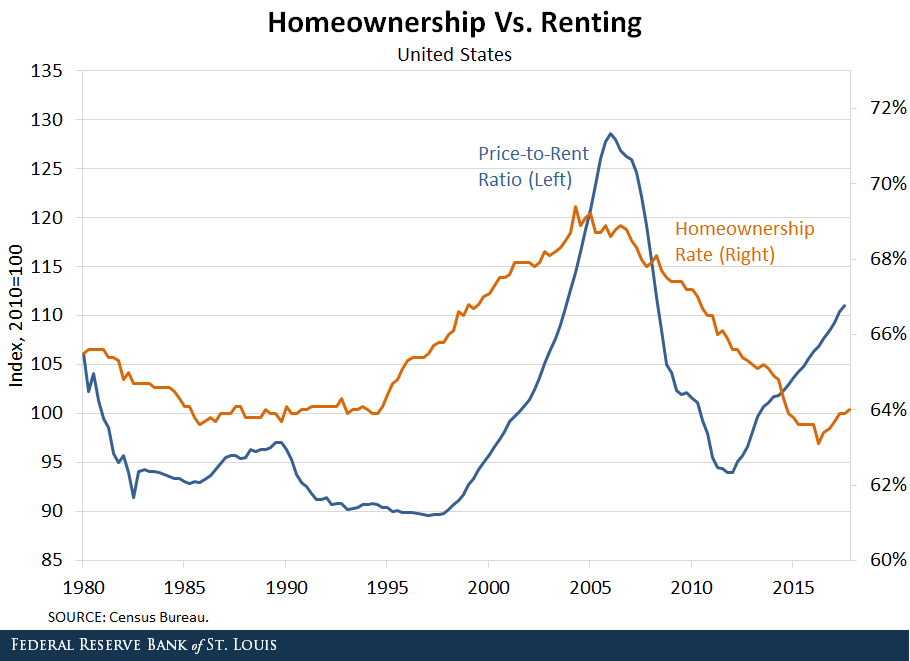

Historically, the cost of buying a house, relative to renting, has been positively correlated with the percent of households that own their home. From 1996 to 2006, both the price of houses and the homeownership rate increased in the U.S. This increasing trend ended abruptly with the global financial crisis that drove house prices and homeownership rates to historically low levels.

It is reasonable to expect prices and homeownership to move in the same direction. A decrease in the number of people who want to buy homes to live in could lead to a decrease in both prices and homeownership. Similarly, an increase in the number of people buying homes to live in could lead to an increase in both prices and homeownership.

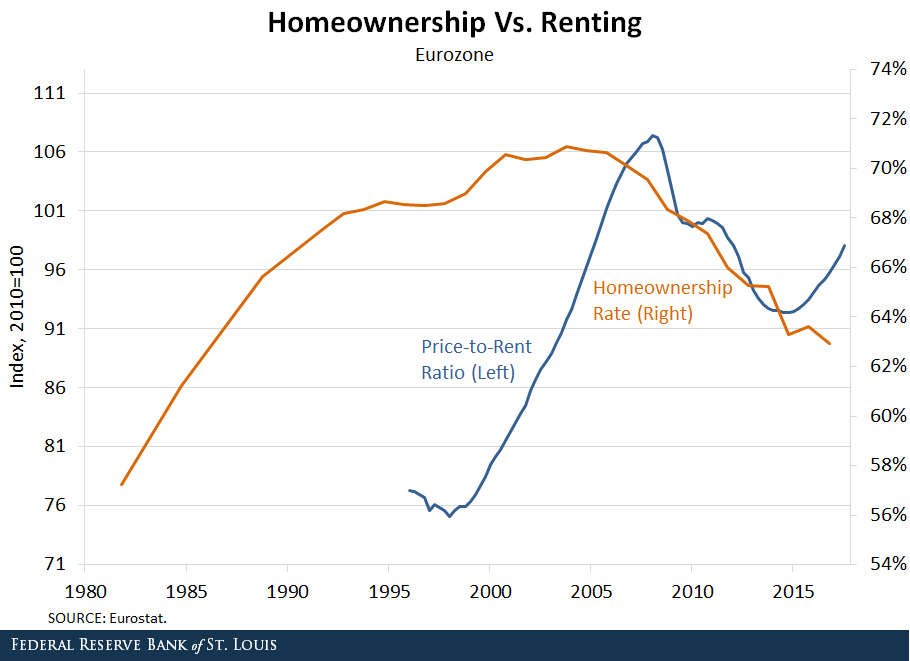

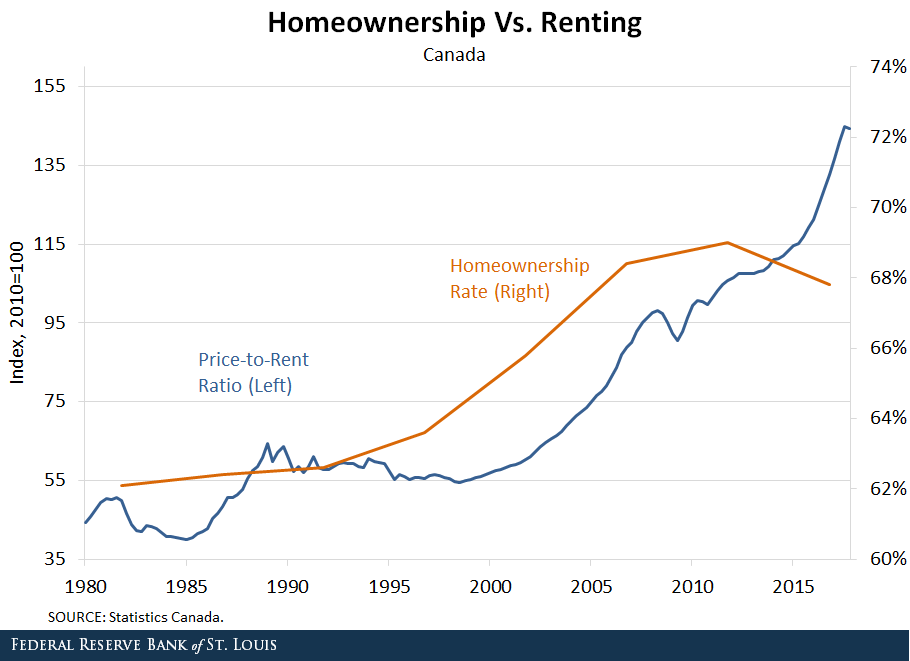

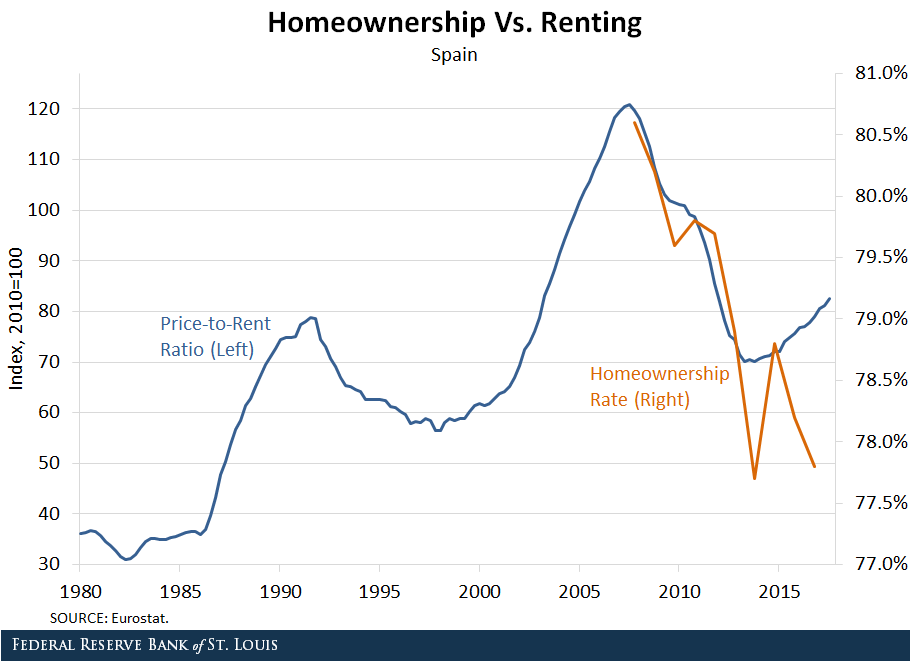

However, recent evidence indicates that the cost of buying a home has increased relative to renting in several of the world’s largest economies, but the share of people owning homes has decreased. This pattern is occurring even in countries with diverging interest rate policies. It is important to delve into this fact and try to find potential explanations. (For trends in homeownership rates and price-to-rent ratios for several developed economies, see the figures at the end of this post.)

Increasing Cost of Housing

The price-to-rent ratio measures the cost of buying a home relative to the cost of renting. Factors like credit conditions or demand for homes as an investment asset affect the price of houses but not the price of rentals. These and other factors cause the price-to-rent ratio to move.

Over the period 1996-2006, the cost of buying a home grew more quickly than the cost of renting in many large economies. For example, the price-to-rent ratio in the U.S. increased by more than 30 percent between 2000 and 2006. Even larger increases occurred in the U.K. and France, where the price-to-rent ratio rose by nearly 80 percent over the same period.

The price-to-rent ratio declined in the wake of the housing crisis in the U.S., the eurozone, Spain and the U.K., but in the past few years, it has started to increase again. The price of houses is again increasing more quickly than the price of rentals.

Decreasing Homeownership

However, the homeownership rate has not increased along with the price-to-rent ratio. The homeownership rate (the percent of households that are owner-occupied) has fallen in several large economies:

- In the U.S., the homeownership rate fell from around 69 percent before the recession to less than 64 percent in 2016.

- In the U.K., the rate fell from nearly 69 percent to around 63 percent.

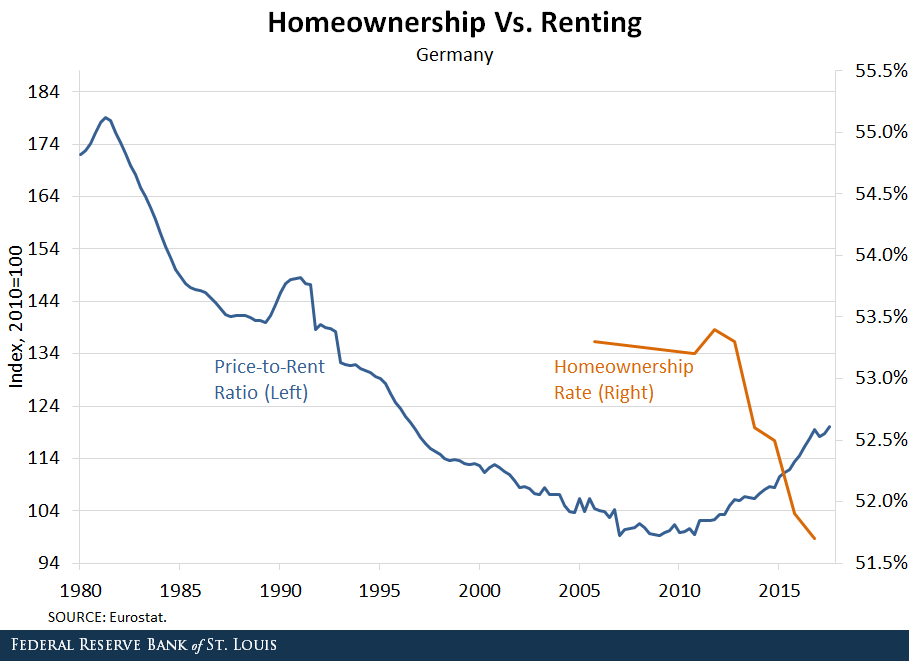

- The homeownership rates in Germany and Italy have also fallen.

Diverging Policies

The pattern of increasing house prices and decreasing homeownership has occurred even in countries with diverging monetary policies:

- By 2016, the Federal Reserve had ended quantitative easing and had begun raising rates in the U.S.

- In contrast, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank continued quantitative easing throughout 2016 and reduced rates.

Nonetheless, the homeownership rate continued to fall in the U.S., the U.K. and many parts of Europe, while the price-to-rent ratio continued to increase.

Housing Supply

Several factors could be driving the decoupling of the price-to-rent ratio and the homeownership rate. From the housing supply side, there is a trend toward decreased construction of starter and midsize housing units.

Developers have increased the construction of large single-family homes at the expense of the other segments in the market. From 2010 to 2016, the fraction of new homes with four or more bedrooms increased from 38 percent to 51 percent. Karson, Evan; McGillicuddy, Joseph; and Ravikumar, B. “The Housing Supply Puzzle: Part 1,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, forthcoming.

This limited supply, particularly for starter homes, could result in increased prices for those homes and fewer new homeowners. One possible factor is regulatory change. The National Association of Home Builders claims that, on average, regulations account for 24.3 percent of the final price of a new single-family home. Emrath, Paul. “Government Regulation in the Price of a New Home,” National Association of Home Builders, May 2, 2016. Recent increases in regulatory costs could have encouraged builders to focus on larger homes with higher margins. Supply may be just reacting to developments in demand that we discuss next.

Housing Demand

From the demand side, there are three leading explanations, which are likely complementary and self-reinforcing:

- Changes in preferences toward homeownership

- Changes in access to mortgage credit

- Changes in the investment nature of real estate

Preferences for homeownership may have changed because households who lost their homes in foreclosure post-2006 may be reluctant to buy again. Burns, John. "The Foreclosure Generation: From 4% above Norm to 7% below Norm Homeownership," John Burns Real Estate Consulting, Sept. 8, 2016. Also, younger generations may be less likely to own cars or houses and prefer to rent them. Godelnik, Raz. "Millennials and the sharing economy: Lessons from a ‘buy nothing new, share everything month’ project," Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 23, June 2017, pp. 40-52.

Demand for ownership has also decreased because credit conditions are tighter in the post-Dodd Frank period. Gete, Pedro; and Reher, Michael. "Mortgage Supply and Housing Rents," The Review of Financial Studies, 2018.

Real Estate Investment

The previous demand arguments can explain why the price-to-rent ratio dropped post-2006. As rents grew relative to home prices, together with the low returns of safe assets, rental properties became a more attractive investment. This attracted real estate investors who bid up prices while depressing the homeownership rate.

Moreover, builders increased their supply of apartments and other multifamily developments. From 2006 to 2016, single-family construction projects declined from 81 percent to 67 percent of all housing starts. Karson, Evan; McGillicuddy, Joseph; and Ravikumar, B. “The Housing Supply Puzzle: Part 2, Rental Demand,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, forthcoming.

There are several types of real estate investors:

- “Mom and dad" investors looking for investment income

- Foreign investors who have increased real estate prices in many of the major cities of the world Favilukis, Jack; and van Nieuwerburgh, Stijn. “Out-of-town Home Buyers and City Welfare,” CEPR Discussion Papers, 2017, No. 12283.

- Institutional landlords like Invitation Homes or American Homes 4 Rent

In fact, since 2016 the real estate industry group has been elevated to the sector level, effective in the S&P U.S. Indices.

In addition, the widespread use of internet rental portals such as Airbnb and VRBO has increased the opportunity to offer short-term leases, increasing the revenue stream from rental housing.

There are several potential explanations, but more research is needed to determine the cause of the decoupling of house prices from homeownership rates and what it means for the economy.

Notes and References

1 Karson, Evan; McGillicuddy, Joseph; and Ravikumar, B. “The Housing Supply Puzzle: Part 1, Divergent Markets.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, April 10, 2018.

2 Emrath, Paul. “Government Regulation in the Price of a New Home,” National Association of Home Builders, May 2, 2016.

3 Burns, John. "The Foreclosure Generation: From 4% above Norm to 7% below Norm Homeownership," John Burns Real Estate Consulting, Sept. 8, 2016.

4 Godelnik, Raz. "Millennials and the sharing economy: Lessons from a ‘buy nothing new, share everything month’ project," Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 23, June 2017, pp. 40-52.

5 Gete, Pedro; and Reher, Michael. "Mortgage Supply and Housing Rents," The Review of Financial Studies, 2018.

6 Karson, Evan; McGillicuddy, Joseph; and Ravikumar, B. “The Housing Supply Puzzle: Part 2, Rental Demand,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses, April 11, 2018.

7 Favilukis, Jack; and van Nieuwerburgh, Stijn. “Out-of-town Home Buyers and City Welfare,” CEPR Discussion Papers, 2017, No. 12283.

Additional Resources

- FRED Blog: Housing Recoveries without Homeowners: National Trends

- Dialogue with the Fed: Is Homeownership Still the American Dream?

- On the Economy: First-Time Homebuyers Still Face Headwinds

- On the Economy: The Hazards of Concentrating Wealth in Homeownership

Citation

Carlos Garriga, Pedro Gete and Daniel Eubanks, ldquoHousing Recoveries without Homeowners: A Global Perspective,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, April 12, 2018.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions