U.S. Workers Face Tougher Competition from Abroad

At the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. became the world’s leading economy, a position that it still holds. By 1950, income per capita in the U.S. was more than 4.5 times the world’s average income per person.

U.S. dominance in the global economy can only be sustained by the superior qualification of its workforce. But how do American workers fare when compared with workers in other nations?

A recent article in The Regional Economist takes up that question. Research Officer and Economist Alexander Monge-Naranjo studied changes in education levels of workers and presented a picture of global workers who are rapidly catching up with their U.S. peers.

“Although American workers have historically been much better trained than their counterparts abroad, that lead has been quickly disappearing in recent years as other countries have accelerated the skill formation of their workers,” the author wrote. “Formal skill through education has become increasingly important in a knowledge-based world economy.”

The Education Gap between the U.S. and Other Developed Countries

In 1950, the majority of workers in France, West Germany, Japan and the U.S. ended formal schooling sometime before the completion of secondary education, according to the author’s analysis of historical data on education levels.

These are low levels of education attainment “that by today’s standards would be deemed insufficient for turning out qualified workers,” Monge-Naranjo wrote.

However, U.S. workers stood out as being far-better educated than their counterparts in those other developed countries.

In the U.S., 7.4 percent of workers had earned at least a college degree. The U.S. workforce also saw a large share of workers who had completed high school (21.6 percent) or had some college education (6.2 percent) as their highest educational level attained.

In contrast, workers in France, West Germany and Japan had a negligible share of workers who earned at least a college degree: less than 2 percent. Of those three countries, Japan had the highest share of workers who had completed high school (11 percent) or had some college education (2.7 percent).

The Education Gap between the U.S. and Developing Countries

The gap was even wider when comparing U.S. workers with those in developing countries in 1950. For instance, only 0.1 percent of Chinese workers and 0.5 percent of Indian workers had completed at least college.

(Figures showing the 1950 education levels of U.S. workers versus workers in other developed countries as well as developing countries can be found in The Regional Economist article “Workers Abroad Are Catching Up to U.S. Skill Levels.”)

The leadership of U.S. workers was due to more than higher incomes, according to Monge-Naranjo.

“The postwar period was a time of large-scale reconstruction and development programs around the world, e.g., the Marshall Plan in Europe, the reconstruction of Japan, the Alliance for Progress in Latin America and the many programs led by the World Bank in developing countries,” the author wrote. “These programs, which were led and financed by the U.S., were carried out by engineers, managers, doctors and many other professionals and technicians from the U.S.”

The Gap Narrows Sharply

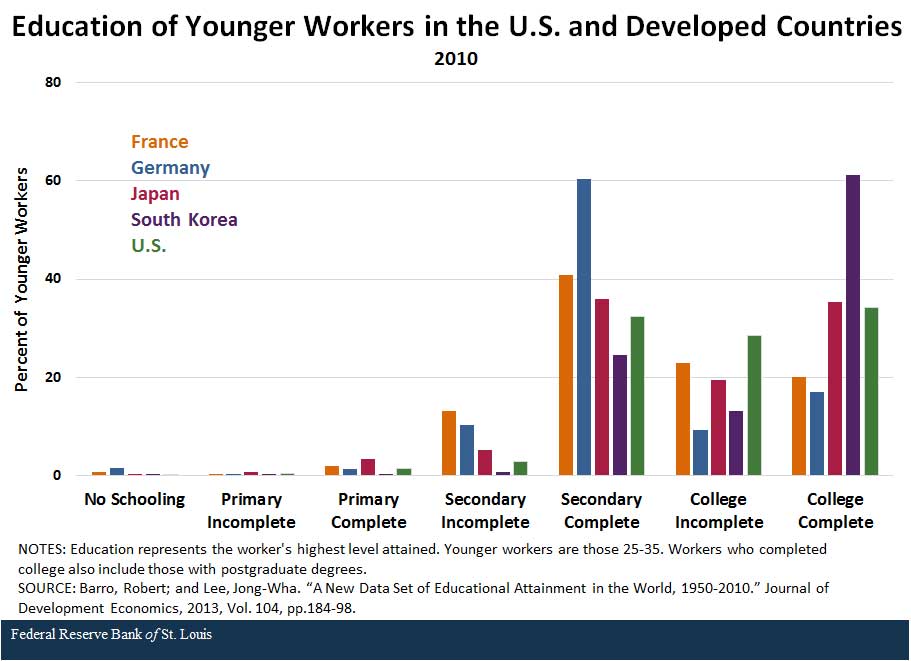

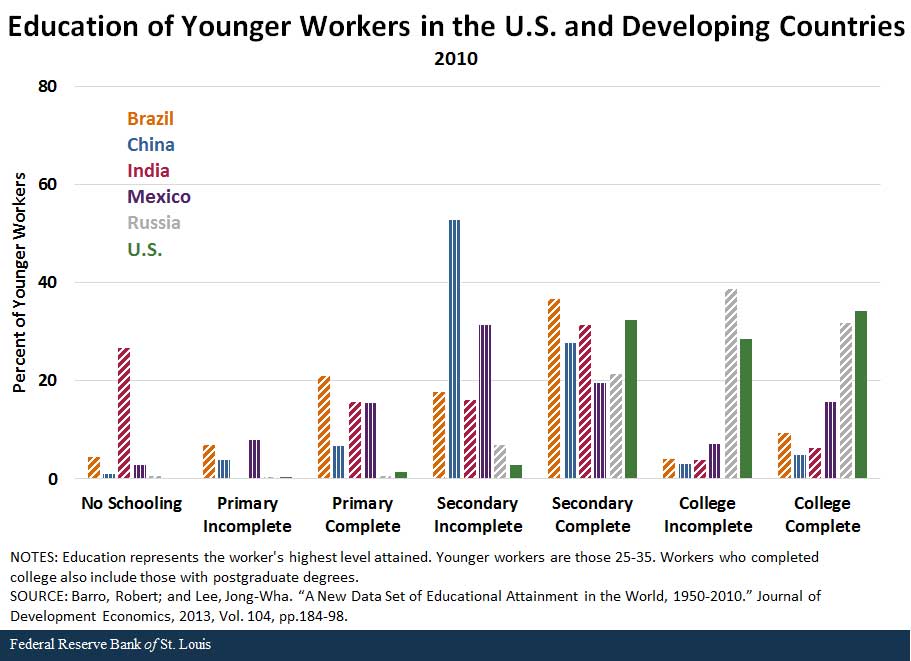

Monge-Naranjo then compared educational levels in 2010. Rather than look at all workers, he focused on younger workers (those aged 25 to 35), adding that “their behavior could better represent the trend for the cohorts of workers in the years to come.”

The figure below shows the highest level of education completed by these workers in developed countries.

This trend of improving educational attainment isn’t just in the developed world. The next figure shows that the fraction of those with at least some college has grown, narrowing the human capital gap with the U.S.

“And even if the fractions of Indian and Chinese college-educated workers remain far below those in the U.S., the population sizes of those countries, and the quality of some of their leading universities, make them relevant suppliers of highly skilled workers for the world economy,” the author wrote.

What’s the Future for U.S. Workers?

The U.S. was once the dominant provider of high-skill workers in the world. Now, its workers must compete in knowledge and skills with many other countries. However, the narrowing education gap also creates opportunities, according to Monge-Naranjo.

“No matter how tough the challenges brought on by more competition become, American workers—of all education levels—can obtain productive opportunities from knowledge emerging from the rest of the world,” he concluded.

Additional Resources

- The Regional Economist: Workers Abroad Are Catching Up to U.S. Skill Levels

- On the Economy: Today’s Immigrants Are More Educated than 50 Years Ago

- On the Economy: Changing Labor Market Leads to Job Polarization

Citation

ldquoU.S. Workers Face Tougher Competition from Abroad,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Oct. 12, 2017.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions