Workers Abroad Are Catching Up to U.S. Skill Levels

At the turn of the 20th century, according to historical estimates, the United States took over from the United Kingdom as the world’s leading economy, a rank it has sustained ever since. Before World War I, in 1913, income per capita in the U.S. was 8 percent higher than in the U.K., 52 percent higher than in all of Western Europe combined and almost 3.5 times the world average income per person.1 By the end of World War II, those gaps were much higher: In 1950, the U.S. income per capita was 38 percent higher than that in the U.K., 112 percent higher than that in Western Europe and more than 4.5 times the world average income per person.2

This global dominance by the U.S. economy can be sustained only by a superior qualification of its workers. This article compares the education of U.S. workers with that of workers in other developed countries and in emerging economies. Although American workers have historically been much better trained than their counterparts abroad, that lead has been quickly disappearing in recent years as other countries have accelerated the skill formation of their workers. Formal skill through education has become increasingly important in a knowledge-based world economy.

Then: U.S. Workers Were No. 1

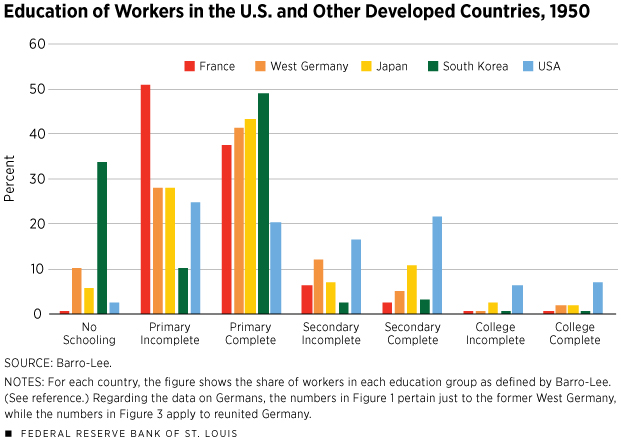

Figure 1 shows the level of education in 1950 for workers in the U.S. and several other countries that are identified today as developed.3 The levels range from no formal schooling to college completed, which includes workers with education beyond an undergraduate degree. The data for this and the other figures cover males and females of all ages; in all cases, the education levels are the maximum achieved for that group.

Notice that even for developed countries, most of the workers in 1950 in France, West Germany, Japan and the U.S. ended their formal schooling somewhere between primary school and the completion of secondary education, levels that by today’s standards would be deemed insufficient for turning out qualified workers. South Korean workers lagged further behind.4

The most remarkable finding in Figure 1 is the degree by which the U.S. workers were far better-educated. Although France had the lowest percentage of workers with no schooling, very few French workers had more than primary education. Albeit less dramatic, a similar pattern holds for West Germany and Japan. All of these countries had negligible fractions of workers who had completed a college education. Indeed, the U.S. is the only country with significant fractions of workers who had completed high school (21.6 percent), who had some college education (6.2 percent) and who had completed college (7.4 percent).

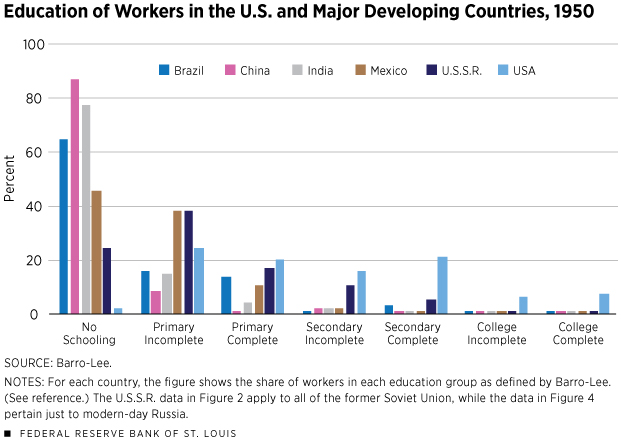

The lead is even wider when U.S. workers are compared with those in major developing countries, as seen in Figure 2. The other countries used in this comparison are Brazil, China, India, Mexico and the U.S.S.R.; nowadays, they are considered the key emerging economies. Most of the workers in Brazil, China, India and Mexico had either no schooling or just some primary schooling in 1950; all of these countries lagged the U.S.S.R., overall. None of these countries had more than a negligible fraction of college-educated workers.

The leadership of U.S. workers was due to more than higher incomes. The postwar period was a time of large-scale reconstruction and development programs around the world, e.g., the Marshall Plan in Europe, the reconstruction of Japan, the Alliance for Progress in Latin America and the many programs led by the World Bank in developing countries. These programs, which were led and financed by the U.S., were carried out by engineers, managers, doctors and many other professionals and technicians from the U.S.

Now: We’re Not in Kansas Anymore

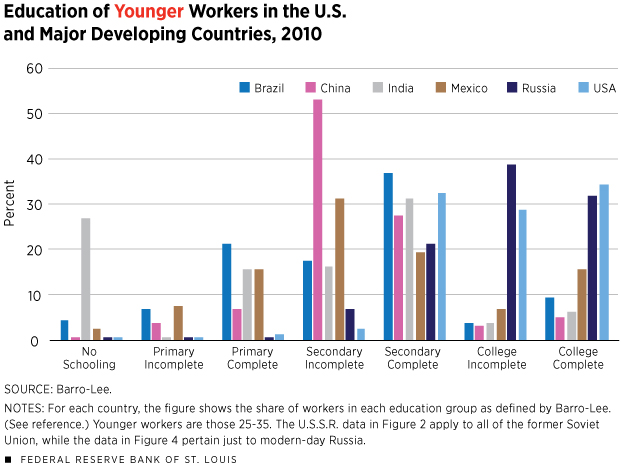

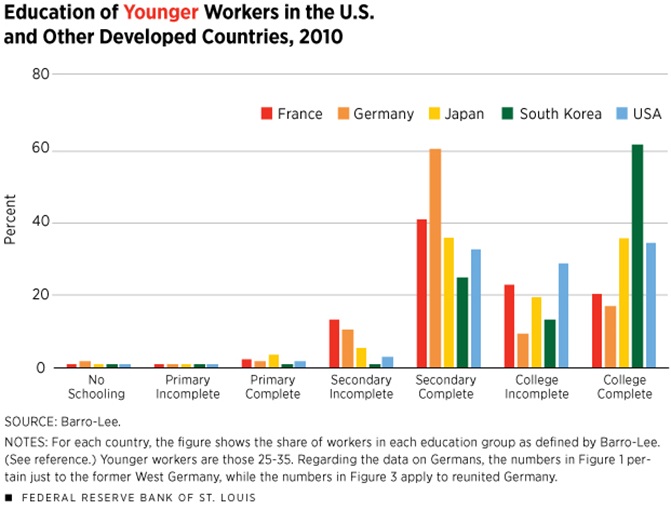

Much has changed since then. For 2010, Figures 3 and 4 show the distribution of workers across the same education levels for the same groups of countries as before. To better capture the trend for the coming years, the figures look only at younger workers, those who are 25-35, as their behavior could better represent the trend for the cohorts of workers in the years to come.

Figure 3 shows that developed countries have all but stopped producing workers with less than complete secondary schooling. The main differences can be seen in the distribution of workers across higher-education groups. First, notice that the main difference between the U.S. and the two European countries is that the latter have a higher fraction of workers who ended their schooling with secondary education and a lower fraction of college-educated workers. This difference is most pronounced with Germany, a country with a strong tradition of technical and vocational secondary education programs. Second, the main difference with the Asian countries is that they are now above the U.S. in the fraction of workers with a complete college education.

Figure 4 shows that there is a global trend to catch up to the U.S. in terms of highly educated workers. All the developing countries have moved toward much higher fractions of workers with some college. And even if the fractions of Indian and Chinese college-educated workers remain far below those in the U.S., the population sizes of those countries, and the quality of some of their leading universities, make them relevant suppliers of highly skilled workers for the world economy.

Conclusion

Although U.S. workers still command a considerable lead with respect to most countries in the world, it is remarkable how strongly other countries have been able to catch up over the past 60 years. From essentially being the sole provider of high-skill workers for both the U.S. and the world economies, U.S. workers must compete, domestically and internationally, in knowledge and skills with workers from many other countries. No matter how tough the challenges brought on by more competition become, American workers—of all education levels—can obtain productive opportunities from knowledge emerging from the rest of the world.Alexander Monge-Naranjo is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Research assistance was provided by Juan Vizcaino, a technical research associate at the Bank. For more on Monge-Naranjo’s work, see https://research.stlouisfed.org/econ/monge-naranjo.

Endnotes

- Data are taken from the Maddison Project. See www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm, 2013 version. [back to text]

- These ratios are computed using income levels that are adjusted for purchasing power differences. See Bolt and van Zanden. [back to text]

- The data are from Barro-Lee. [back to text]

- To be sure, in 1950, South Korea was far from being a developed country, with a per capita income of only 8.9 percent of that of the U.S. However, by 2010, South Korea clearly was a developed country, with per capita income equal to 72 percent of that for the U.S. and higher than the average per capita income in Western European countries. [back to text]

References

Barro, Robert; and Lee, Jong-Wha. A New Data Set of Educational Attainment in the World, 1950-2010, Journal of Development Economics, 2013, Vol. 104, pp.184-98.

Bolt, Jutta; and van Zanden, Jan Luiten. The Maddison Project: Collaborative Research on Historical National Accounts. The Economic History Review, 2014, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 627-51. See http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1468-0289.12032.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us