Measuring Labor Share in Latin American Countries

One of the challenges of measuring a country’s labor share involves factoring in self-employed people. In this blog post, we look at the labor share for several Latin American countries, and several ways in which it can be estimated.

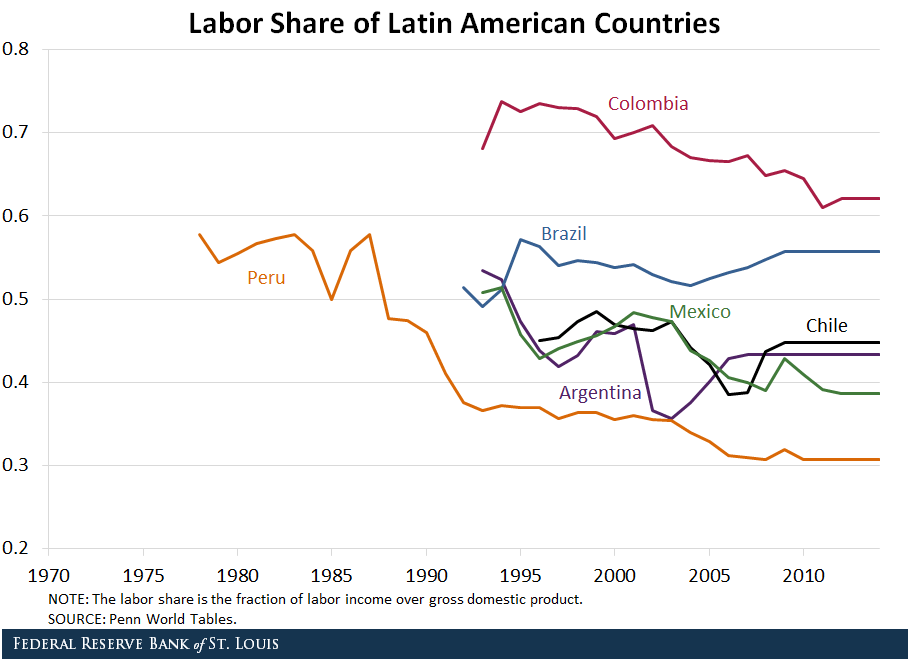

The labor share is the fraction of labor income over gross domestic product. The figure below shows the labor share in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

As the figure shows, the labor share varies widely among these countries. For some, it also shows considerable differences over time. However, estimating the labor share accurately can be challenging, and the results will vary depending on what assumptions are made.

Assumptions for Estimating Labor Share

To have a good estimate of the labor share, it is crucial to have good data on labor compensation. Labor income is widely observable for employed individuals that work in formal firms. The challenge lies in estimating labor income of self-employed individuals, because their income contains contributions from labor and capital.

The Penn World Tables (PWT)1 have data for several estimates of the labor share. The figure above reports what PWT considers the best measure based on several criteria.

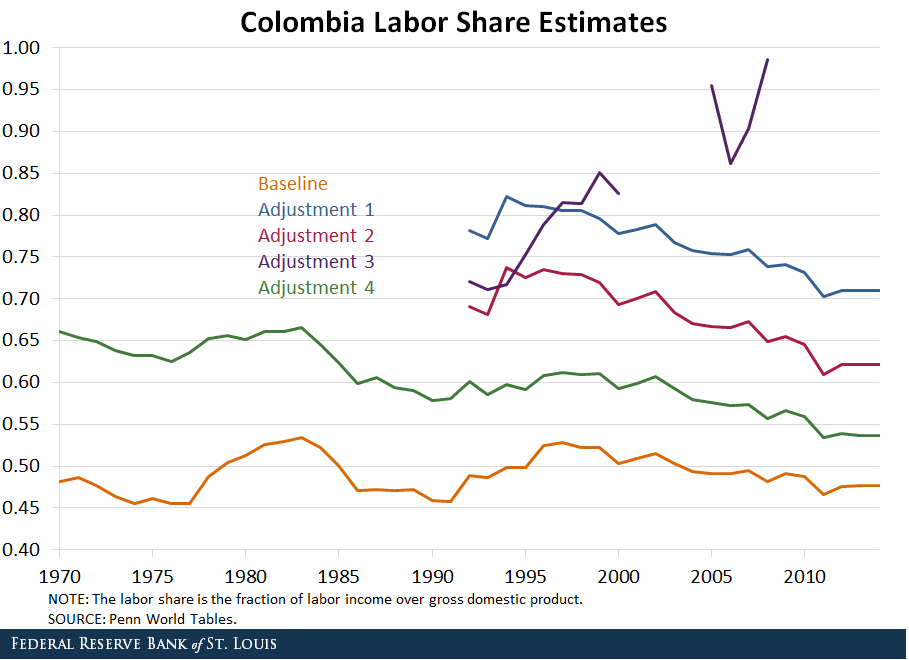

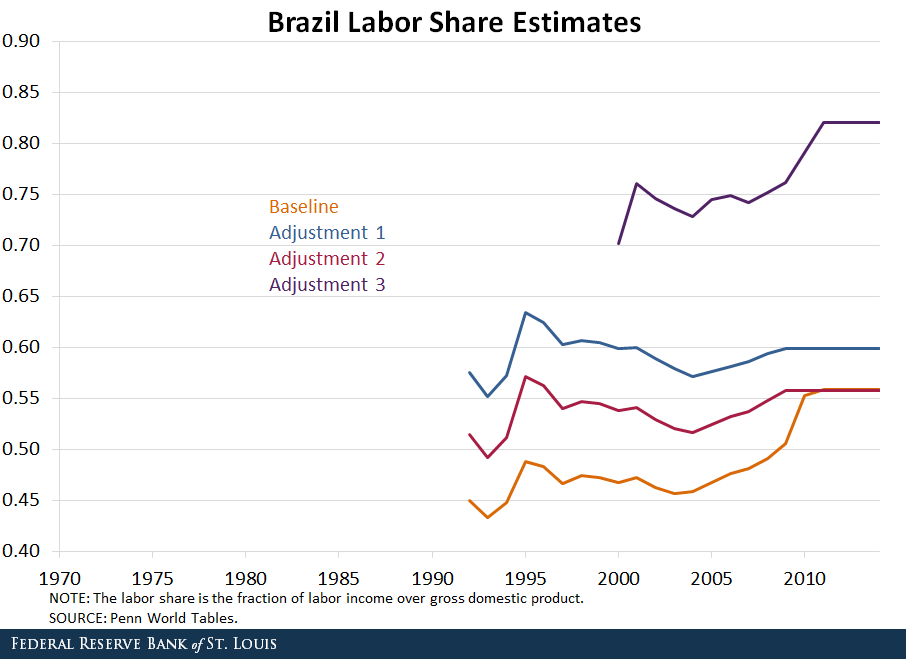

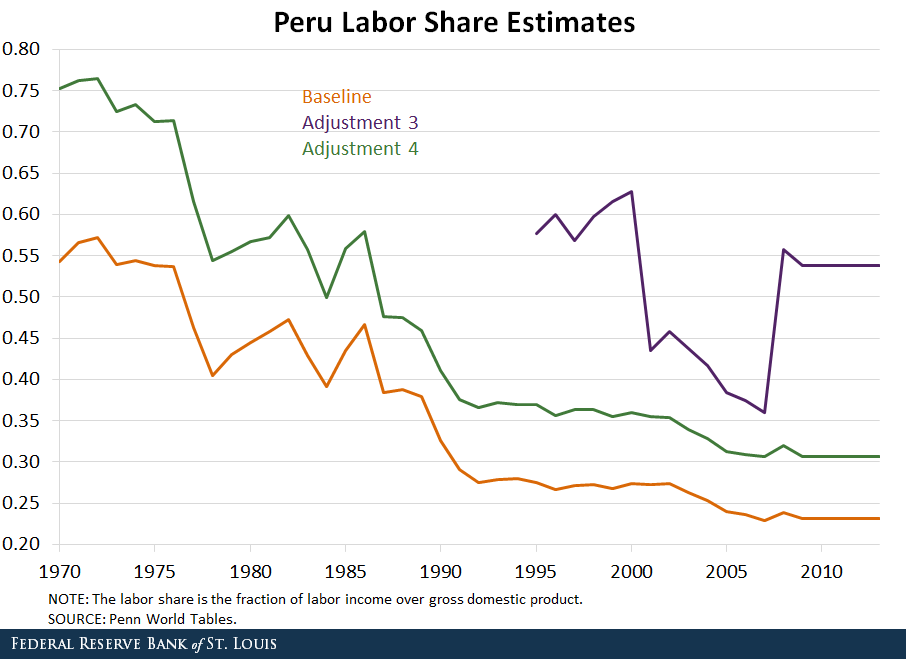

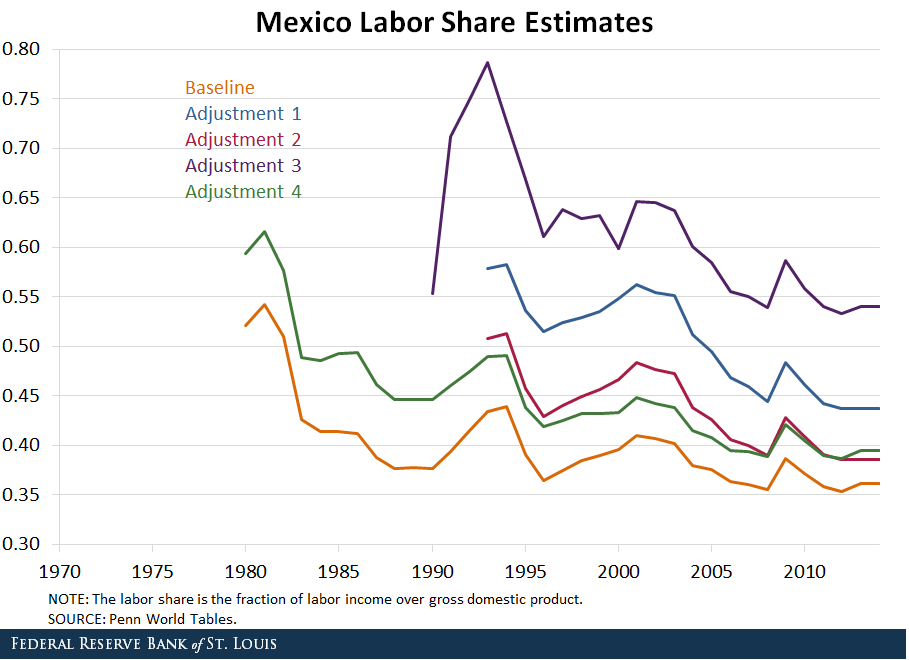

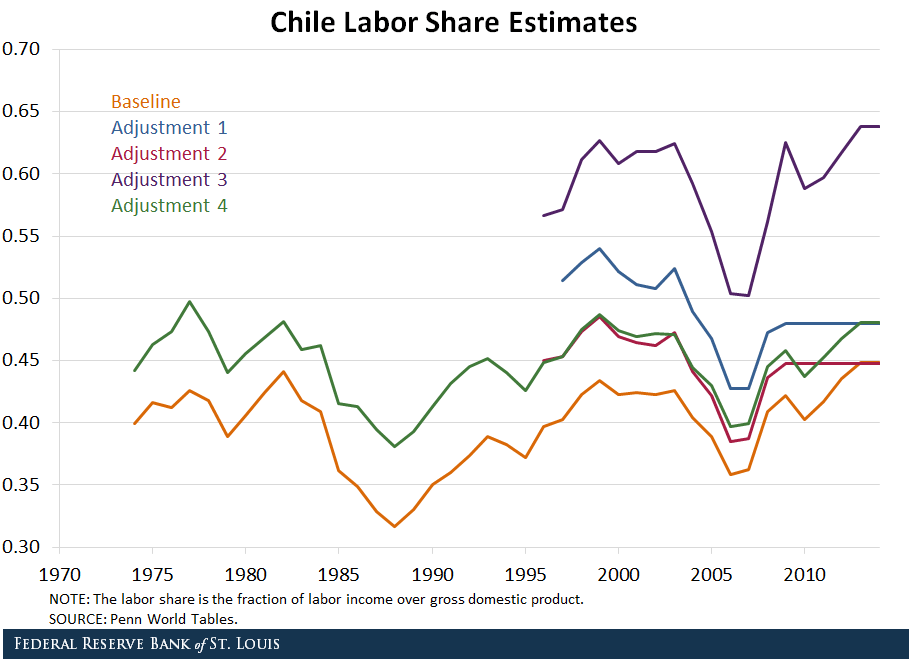

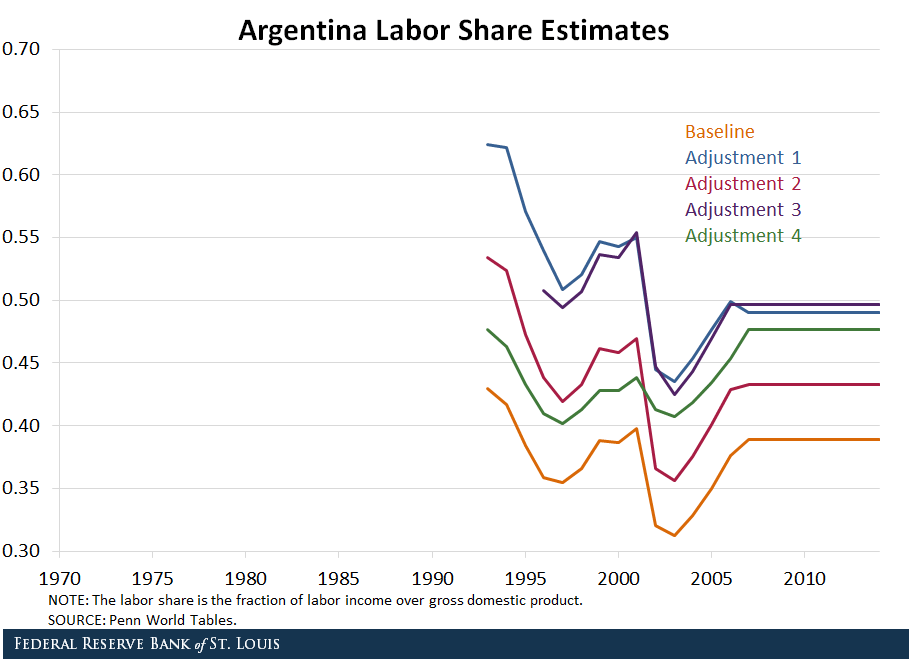

However, the labor share varies significantly for each country based on what assumptions are made and the quality of data. The figures at the end of the post show the variance depending on what assumptions are used.

Baseline Assumption

In these figures, the baseline is the share of labor compensation of employees. Since it does not include self-employed income, it serves as a lower bound for the estimate of the labor share.

The First Assumption

Some countries report mixed-income data, which is total self-employed income. For the countries that report mixed-income data, adjustment 1 adds all mixed income to total labor compensation, and this adjustment serves as an upper bound. However, since self-employed income contains both labor and capital income, it overestimates the labor share.

The Second Assumption

A common assumption for adjusting the labor share of self-employed income is to assume that self-employed individuals use labor and capital in the same proportion as the rest of the economy. Adjustment 2 does that and is considered the most reasonable estimate. Of the six Latin American countries studied, only Peru does not report mixed-income data, so additional information is required.

The Third Assumption

Adjustment 3 uses information on the total number of self-employed people and assumes that they earn the same average wage as employees. However, this tends to overestimate the labor income of the self-employed in developing countries.

Because self-employed workers tend to make up a larger proportion of workers in developing countries, this overestimate can distort measures of the labor share for developing nations.2 Indeed, we see that adjustment 3 is very high in the following figures.

The Fourth Assumption

A 2015 paper suggests another way to estimate labor income of self-employed individuals that may be superior to Adjustment 3 for poorer countries.3 Adjustment 4 assumes that all the self-employed work in the agriculture sector, so the entire value added in agriculture is added to labor compensation.

This adjustment is reasonable in poorer nations, because agriculture employs about half of the self-employed and uses little capital.4 However, it might not be very accurate for countries that are already in the second stage of their structural transformation.

This measure, therefore, gives a rough idea of the labor share in poorer countries and is reported in the earlier figure for Peru. Also, adjustment 4 is fairly similar to Adjustment 2 for the rest of the countries.

Conclusion

In summary, estimates of the labor share can vary depending on availability of data and what assumptions are made for measuring the share of labor income of the self-employed. This can make a huge difference for developing countries with a large number of self-employed individuals.

Notes and References

1 Feenstra, Robert C.; Inklaar, Robert; and Timmer, Marcel P. “The Next Generation of the Penn World Table,” American Economic Review, 2015, Vol. 105, No. 10, pp. 3150-182.

2 Gollin, Douglas. “Getting Income Shares Right,” Journal of Political Economy, 2002, Vol. 110, No. 2, pp. 458-74.

3 Feenstra, Robert C.; Inklaar, Robert; and Timmer, Marcel P. “The Next Generation of the Penn World Table,” American Economic Review, 2015, Vol. 105, No. 10, pp. 3150-182.

4 Timmer, Marcel. “The World Input-Output Database (WIOD): Contents, Sources and Methods,” WIOD Working Paper Number 10, May 22, 2014.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Comparing the Latin American and European Debt Crises

- On the Economy: How Income Inequality Is Affected by Labor Share

- On the Economy: What Is the Informal Labor Market?

Citation

Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría and Brian Reinbold, ldquoMeasuring Labor Share in Latin American Countries,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 23, 2017.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions