Life Experience and Loan Delinquencies

Today’s post is the second in a two-part series on the link between demographic characteristics and the risk of loan delinquency.

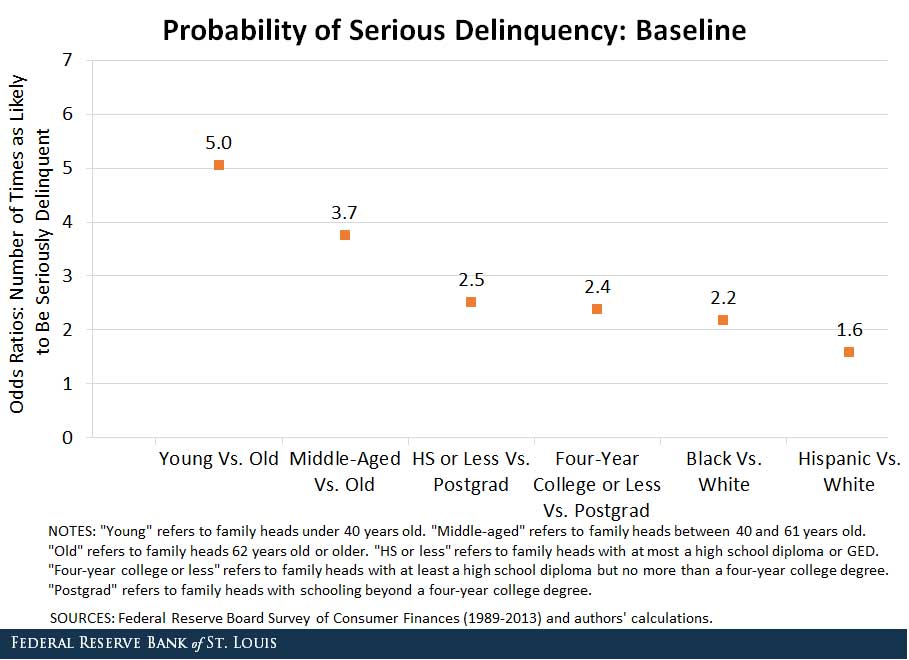

Our previous post looked at one possible explanation for why some demographic groups were more likely to become seriously delinquent—i.e., miss at least two consecutive payments—on a loan or other payment obligation. The post, which was based on an issue of In the Balance, examined whether younger, less-educated and nonwhite families had a greater “taste for risk” than older, better-educated and white families. This post examines whether structural factors rather than individual risk preferences may provide a better explanation.

Taste for Risk?

The authors of the In the Balance—Senior Economic Adviser William Emmons, Senior Analyst Lowell Ricketts and Intern Tasso Pettigrew, all with the St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability—found that eliminating so-called "bad choices" and "bad luck" reduced the likelihood of serious delinquency. With the exception of Hispanic families, this did not get rid of disparities in delinquency risk relative to the lower-risk reference group.

However, this exercise was based on the idea that the young (or less-educated or nonwhite) families’ financial and personal choices, behavior and exposure to luck could conform to those of the old (or better-educated or white) families. The authors suggested that such an approach may not be realistic.

A Lack of Choice?

“We believe a more realistic starting point for assessing the mediating role of financial and personal choices, behavior and luck in determining delinquency risk is a family’s peer group,” the authors wrote. They looked at how an individual family’s circumstances differ from its peer group, hoping to capture the “gravitational” effects of the peer group.1

In particular, they examined how a randomly chosen family fared against the average of its peer group, such as how much debt a young black or Hispanic family with at most a high school diploma has compared to the family’s peer-group norm.

“We assume that the distinctive financial or personal traits associated with a peer group ultimately derive from the structural, systemic or historical circumstances and experiences unique to that demographic group,” the authors wrote.

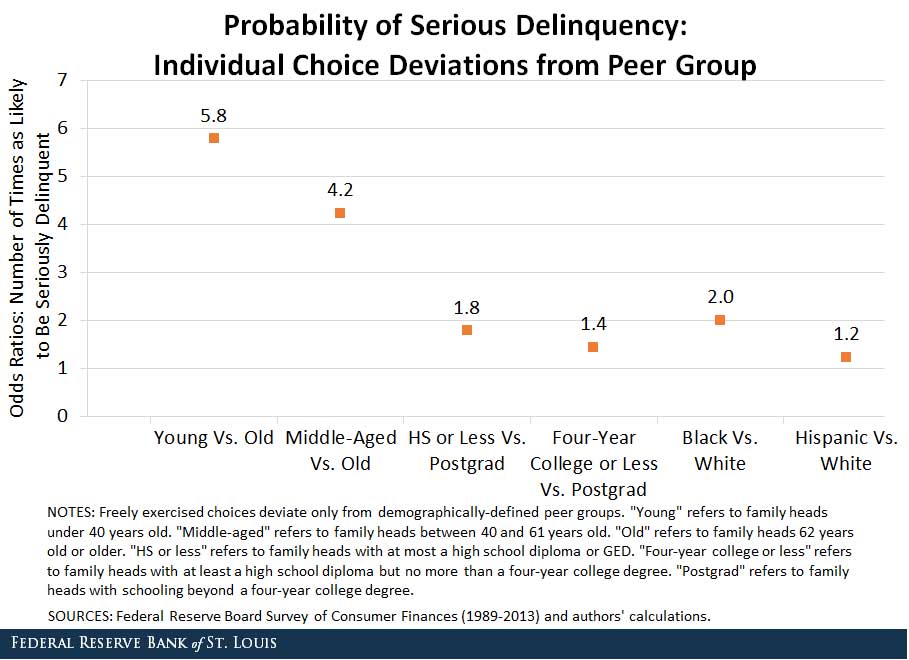

When assuming that individual families’ choices extend only to deviations from peer-group averages, the authors estimated that:

- A family headed by someone under 40 years old is 5.8 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone 62 years old or more.

- Middle-aged families (those with a family head aged 40 to 61 years old) are 4.2 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as old families.

- A family headed by someone with at most a high school diploma is 1.8 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone with postgraduate education.

- A family headed by someone with at most a four-year college degree is 1.4 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone with postgraduate education.

- A black family is 2.0 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a white family.

- A Hispanic family is 1.2 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a white family.

The odds are similar to those that were not adjusted, as seen in the figures below. (For 95 percent confidence intervals, see “Choosing to Fail or Lack of Choice? The Demographics of Loan Delinquency.”)

These demographic groups still appear to have a higher delinquency risk than older, better-educated and white families. This suggests that younger, less-educated and nonwhite families may have little choice in the matter.

“The striking differences in delinquency risk across demographic groups cannot be explained simply by referring to differences in risk preferences,” Emmons, Ricketts and Pettigrew wrote. “Instead, we suggest that deeper sources of vulnerability and exposure to financial distress are at work.”

The authors also concluded: “Families with ‘delinquency-prone’ demographic characteristics—being young, less-educated and nonwhite—did not choose and cannot readily change these characteristics, so we should refrain from adding insult to injury by suggesting that they simply have brought financial problems on themselves by making risky choices.”

Notes and References

1 Each family was assigned to one of 12 peer groups, which were defined by age (young, middle-aged or old), race or ethnicity (white or black/Hispanic) and education (at most a high school diploma or any college up to a graduate/professional degree).

Additional Resources

- In the Balance: Choosing to Fail or Lack of Choice? The Demographics of Loan Delinquency

- On the Economy: To Borrow, or not to Borrow?

- On the Economy: What Was Behind the Boom and Bust in House Prices?

Citation

ldquoLife Experience and Loan Delinquencies,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Nov. 29, 2016.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions