How Successful Is the Fed at Controlling Interest Rates?

The federal funds rate is the main policy tool the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) uses to affect the U.S. economy. But the federal funds rate is not the only interest rate that matters for the U.S. economy. There are many other short-term interest rates and long-term interest rates that affect the U.S. economy.

The standard argument is that through arbitrage, movements in the federal funds rate will spill over and affect interest rates across the yield curve. The FOMC controls the federal funds rate through the supply of reserves, and reserves are a close substitute for short-term U.S. government debt obligations. So, is the Fed able to influence short-term interest rates on government debt at a three-month, six-month, one-year and two-year horizon in a desired direction? Is it able to influence longer-term interest rates as well?

Quantitative Easing, Liftoff and Interest Rates

One way to shed some light on these questions is to look at the effect quantitative easing (QE) had on interest rates. The second and third rounds of quantitative easing (dubbed QE2 and QE3, respectively) aimed to lower short- and longer-term yields. The goal was to make it cheaper to borrow for consumption and investment.

On the other hand, the December liftoff was intended to push up interest rates. The official announcements of these policy actions occurred in the FOMC statement, but most were hinted at well in advance of the meeting in which they were implemented. Since asset prices and interest rates will price these hints in, one needs to look at the level of interest rates before the first hint that the FOMC will do something. Assuming that the first hint is a “surprise,” we would expect that interest rates on government debt would fall across the yield curve after the first signal of QE2 and QE3. Liftoff should do the opposite: Once it becomes clear the FOMC will raise rates, all rates across the yield curve should rise.

Did this happen? In the following charts, we plotted the yield curve on U.S. government debt before the announcement of QE2, QE3 and liftoff. We then plotted the yield curves shortly after the announcement and six months after the announcement. Determining the date of first hint is obviously subjective. Nevertheless, we feel that our dates are fairly accurate.

For QE2, we chose the Aug. 10, 2010, FOMC statement as the first hint. It announced a plan to reinvest maturing assets that were acquired through QE1 and signaled to markets that another round of QE could be coming soon. For QE3, we chose then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s Aug. 31, 2012, speech, in which he indicated that QE3 could be announced in the near future. While liftoff is a bit more difficult to pinpoint because it was more of a question of when than if, we chose the release of the Oct. 28 FOMC statement, which signaled a high likelihood for a December rate hike.

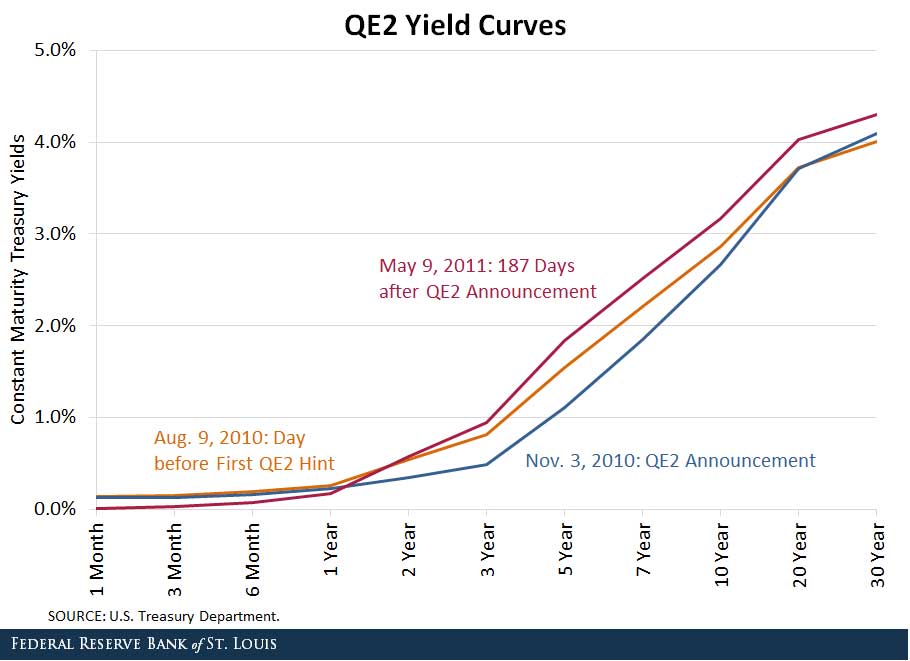

The figure above covers QE2 and plots three U.S. Treasury yield curves:

- Aug. 9, 2010, the day before the Fed first hinted at QE2

- Nov. 3, 2010, the day the Fed announced QE2

- May 9, 2011, roughly half a year later

By the date of the official announcement, yields had fallen relative to pre-hint levels for all Treasury securities ranging from one-month to 20-year maturity. However, about six months after the announcement, only one-month through one-year maturities still had yields below the pre-hint levels. Longer-term yields were higher than their pre-announcement levels.

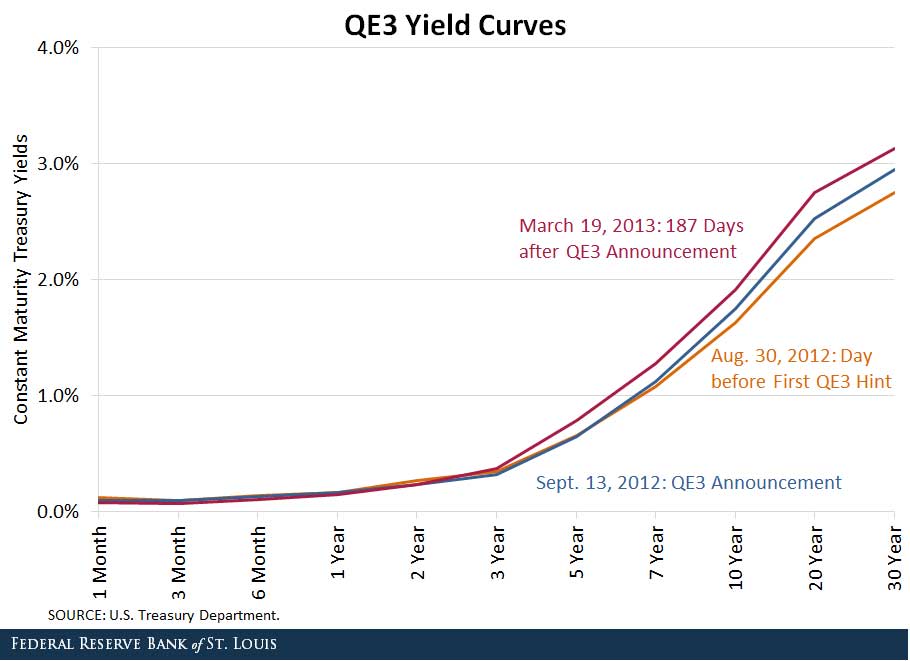

The figure above plots the yield curves around QE3. Similar to the yield curve reaction following QE2, short-term yields were still low long after the policy was implemented, but long-term yields were higher 187 days out.

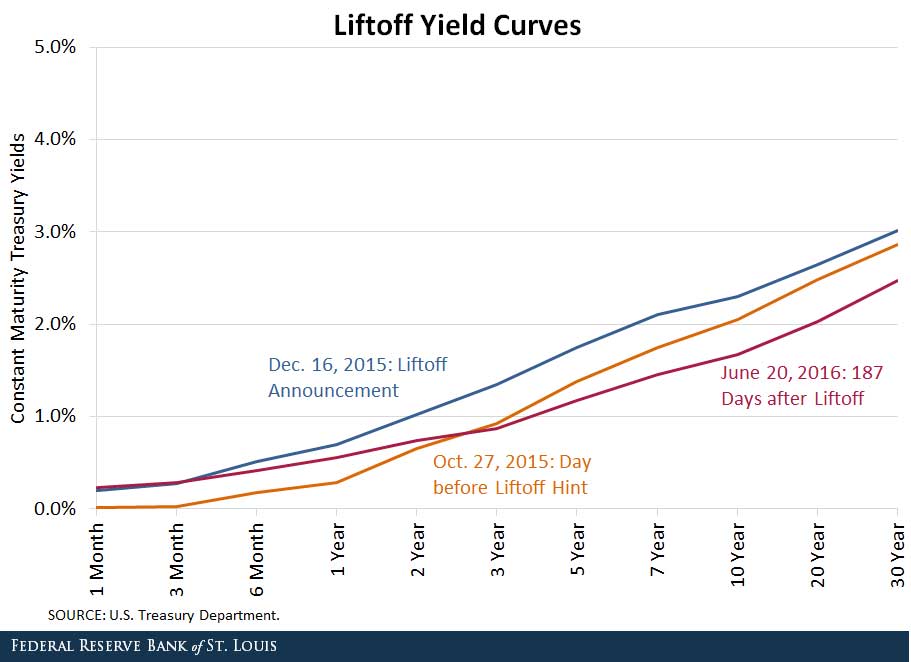

The figure above plots the yield curves around liftoff. Again, short-term interest rates moved up just as theory would predict. But six months later, longer-term yields fell relative to where they were before liftoff.

So what is the takeaway? The Fed appears to have significant control over short-term interest rates and can move them in desired directions. However, longer-term interest rates are much harder to control, particularly for an extended period of time. If long-term rates matter most for investment decisions, spending on consumer durables and housing, then it is more difficult for the Fed to control these aspects of the economy over an extended period of time.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Negative Interest Rates: A Tax in Sheep’s Clothing

- On the Economy: Households Less Likely to Say Using Credit Is OK

- On the Economy: Are Banks More Profitable When Interest Rates Are High or Low?

Citation

Christopher J. Waller and Jonas Crews, ldquoHow Successful Is the Fed at Controlling Interest Rates?,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, July 11, 2016.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions