How Credit Card Debt Default Has Evolved

By Juan Sanchez, Senior Economist

Some individuals use credit card debt to avoid the decline in consumption that follows a reduction in income.1 Paradoxically, in some situations, excessive borrowing forces individuals to reduce consumption to afford large credit card payments. In those situations, some individuals find it beneficial to avoid the reduction in consumption by skipping credit card payments and becoming delinquent.

While delinquency is attractive to smooth consumption, it has important costs:

- Debt increases quickly during delinquency because credit cards charge penalty rates.

- Future access to credit deteriorates because credit scores worsen during delinquency.

In this post, we analyze the recent evolution of credit card default. The definition of “default” considered here is broader than bankruptcy. It also includes accounts with debt payments delayed by 120 days or more.

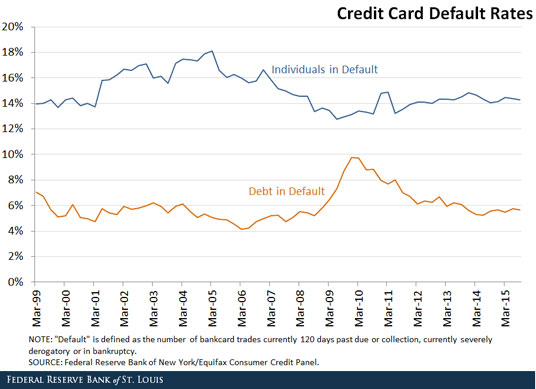

In the figure below, two alternative measures of default are presented, which were constructed using Federal Reserve Bank of New York/Equifax Consumer Credit Panel:

- The percent of individuals with at least one account in default

- The percent of total debt that is in default

Two distinct episodes are worth an explanation:

- The period leading up to the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA)

- The Great Recession

First, in the period leading up to the BAPCPA, which increased the cost of filing for bankruptcy, the percent of individuals in default increased, while the debt in default did not. This implies that the average size of debt in default decreased during this period. A potential explanation is that many individuals rushed to file bankruptcy before the change in the regulation. Therefore, they defaulted with smaller amounts of debt than before.

Second, during the recession, the debt in default increased, while the percent of individuals in default decreased. This resulted in an increase in the average size of debt in default. The rise in the cost of filing bankruptcy caused by the implementation of BAPCPA may help with reconciling these facts. This change prevented many individuals from filing bankruptcy, but those who filed had larger amounts of debt.2

Notes and References

1 This is referred to as consumption smoothing.

2 A caveat is that the arguments presented above use the change in bankruptcy filing costs to talk about the dynamics of a default measure that include both informal bankruptcy (through delinquency) and formal bankruptcy. My co-authors and I studied these two episodes in more detail in: Athreya, Kartik; Sanchez, Juan; Tam, Xuan; and Young, Eric. “Labor Market Upheaval, Default Regulation and Consumer Debt.” January 2015, Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 18, Issue 1, pp. 32-52.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: How Has the Bankruptcy Act Affected Bankruptcy Filings?

- On the Economy: Costs of Defaulting on Credit Card Debt Vary

- On the Economy: The Relationship between Wage Growth and Inflation

Citation

Juan M. Sánchez, ldquoHow Credit Card Debt Default Has Evolved,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Dec. 22, 2015.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions