The Link between Default and Depreciation

In the aftermath of the Argentine default (or semi-default, depending on how you look at it), the Argentine peso has fallen considerably, with reports of market expectations that the default would cause 11 percent depreciation in the currency.1

One should not take for granted, however, that currency markets and sovereign debt markets would be inexorably tied: The Argentine peso trades on international markets to facilitate mostly private-sector trade between Argentina and the rest of the world, while Argentine sovereign debt is issued for the government to borrow and its default is a reflection of the public-sector finances. Why is this link so intimate? Are there implications of this linkage?

This idea will be fleshed out further, but in this post I will posit that currency depreciation acts as a punishment for default. It makes imports from the rest of the world more expensive and hurts consumers in Argentina. Because this effect is relatively predictable, it acts as a deterrent to default, which in turn makes default less likely and increases countries’ borrowing ability.

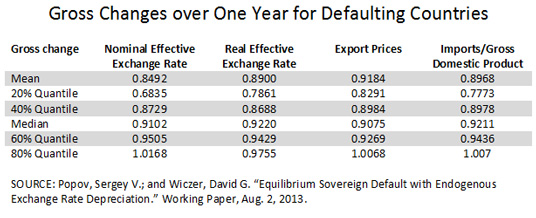

The table below shows that the relationship between currency depreciation and default is rather strong and predictable. In this table, we take the record of defaults (as categorized by Standard & Poor’s since 1970) and look at how their exchange rates and trade flows changed. There is obviously variation across countries’ experiences, and so the table shows that the vast majority experience some depreciation. Note the depreciation occurs when looking at both nominal and real terms of trade: This is not just an effect of faster inflation in the defaulting country but rather a change in the terms of trade.

Why would default cause depreciation? Sovereign default on foreign currency debt makes foreign creditors reluctant to deal with borrowers of all sorts from defaulting countries. And because importers and exporters from defaulting countries require some short-term credit to facilitate trade, defaults can increase the risk in the trade and hence turn prices against them.

Locals may also look to hold more foreign currency as a precaution, because government willingness to default on debt, even only in foreign markets, makes assets like government bonds denominated in the local currency less valuable.

Depreciation has two distinct effects on local economies:

- Foreign goods become more expensive to import.

- Locally produced substitutes become relatively cheaper.

Hence, the depreciation both hurts consumers and can spur some increase in production. The relative importance of imports to the local basket of purchases can, therefore, be a factor in how much default hurts. This cost of default is not trivial, because the costs of sovereign default are generally ill-defined. A personal default has certain legal pathways that are generally well defined, but this is not so when a country stops paying.

When considering how much to lend and at what interest rates, lenders need to consider the countries’ likelihood of repaying, and this involves calculating how much it would hurt countries to default. In short, harsher punishments can increase access to foreign credit because countries are less likely to default if that would be more painful. Depreciation is truly a double-edged sword, serving as the punishment that allays lenders’ fears of default, but also hurting the ordinary bystanders to a government’s actions in the case of default.

Notes and References

1 Porzecanski, Katia. “Argentine Default Sours Outlook for Peso as Talks Ordered.” Bloomberg Businessweek, Aug. 4, 2014. It should be noted that this article also cited a JPMorgan projection that the government might intervene in currency markets to prop up its peso and make the default appear less legitimate.

Additional Resources

- On the Economy: Comparing International Bond Yields

- On the Economy: Debt Crisis in Europe Easing, but Not Over

- On the Economy: Recent ECB Policy and Inflation Expectations

Citation

David G Wiczer, ldquoThe Link between Default and Depreciation,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 25, 2014.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions