Recent ECB Policy and Inflation Expectations

On May 8, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi stated the ECB would be “comfortable” taking measures to boost inflation.1 On June 5, the policy was resoundingly announced. For example, a press article said that “Draghi unveil(ed) historic measures against deflation threats.”2 The “historic” measures “unveiled” consisted of reducing the ECB’s benchmark rate to 0.15 percent, reducing the ECB’s deposit rate to -0.1 percent and announcing a bank lending facility of roughly $550 billion. The ECB also announced it was working on a plan to potentially conduct outright asset purchases.

It can be said that, at least temporarily, the policy spurred several of the typical financial market effects that successful monetary policy is thought to have: Some bond yields fell, the euro depreciated against the U.S. dollar, and stock prices rose in Germany. However, there has been no effect on breakeven inflation expectations. This lack of reaction in inflation expectations can be interpreted as a signal that market participants do not expect the policy to work in terms of boosting inflation.

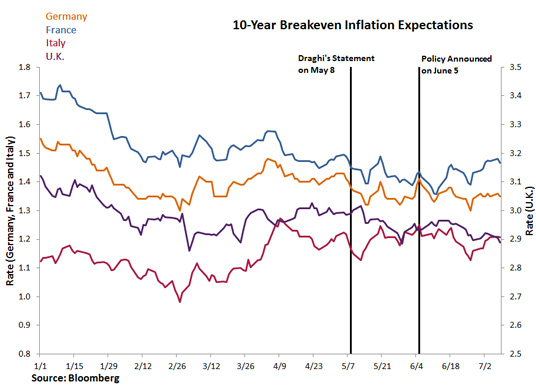

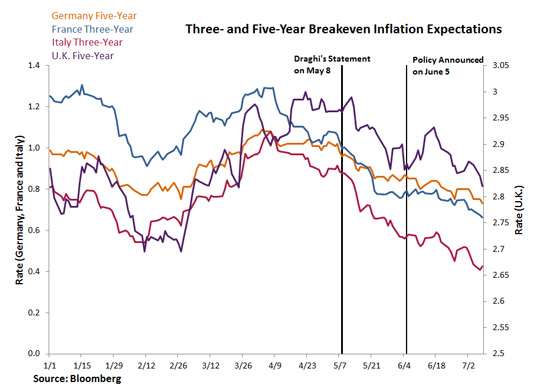

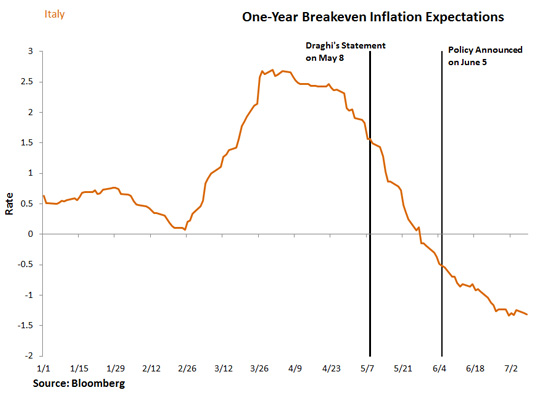

Breakeven inflation expectations are defined as the additional yield provided by nominal debt with respect to the yield on inflation-indexed debt. Many analysts prefer breakeven inflation expectations over self-reported inflation expectations extracted from surveys because they depend on the actual behavior of market participants. The figures below show breakeven inflation expectations implied by sovereign bonds from the eurozone and the U.K.:

- The first figure shows that 10-year breakeven inflation expectations were flat for Germany, France and Italy, as well as for the U.K. (which is not directly affected by ECB policy).

- The second figure shows that breakeven inflation rates for shorter-maturity securities continued their gradual decline during the announcement and the policy adoption period, again in tandem with British securities.

- The third figure shows how one-year breakeven inflation expectations calculated from Italian debt yields fell swiftly throughout the policy announcement and adoption period, entering deflationary territory on May 28.

If we compare the economic landscape faced by the ECB in May 2014 with the landscape faced by the Federal Reserve in mid-2010 (when a possible second round of quantitative easing [QE2] was first announced), some variables are somewhat similar. For example:

- The fed funds rate target had been 0-0.25 percent since mid-December 2008, while the benchmark ECB rate had been at 0.25 percent since November 2013.

- The U.S. unemployment rate was 9.8 percent and slightly lower than one year before, while the unemployment rate in the eurozone was 11.6 percent in May 2014, 0.4 percentage points lower than one year before.

- U.S. consumer price index (CPI) inflation was at 1.1 percent and declining with respect to the previous year, while CPI inflation in the eurozone was 0.5 percent in May 2014 and declining with respect to the previous year.

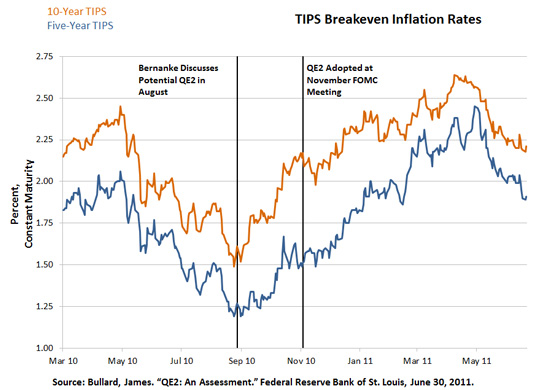

However, QE2, a $600 billion program of outright asset purchases, seems to have boosted inflation expectations. The figure below shows how breakeven inflation expectations implied by five- and 10-year U.S. Treasury inflation-protected securities, reversed their downward trend around the time then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke discussed a possible QE2 during a speech in August 2010, and continued rising as the policy was adopted at the November 2010 Federal Open Market Committee meeting.3

Arguably, the two central banks were operating in somewhat similar macro environments. If so, the reasons behind the dissimilar reactions of breakeven inflation expectations to unconventional policy should be attributed to differences in the particular policies adopted. The key difference between the ECB’s lending facility and QE2 is that the lending facility depends on its usage by private banks.4 Furthermore, while the ECB announced a possible QE program, some market participants may not find this statement completely credible.5 Two obstacles for outright asset purchases by the ECB have been pointed out, both related to the assets to be purchased:

- First, there are political difficulties in deciding whose sovereign bonds to buy: Spanish, Italian, German or other?

- The second obstacle is the relative thinness of mortgage-backed securities markets throughout the eurozone.

Notes and References

1 Blackstone, Brian. “Draghi: ECB ‘Comfortable With Acting Next Time.’” The Wall Street Journal, May 8, 2014.

2 Black, Jeff; and Riecher, Stefan. “Draghi Unveils Historic Measures Against Deflation Threat.” Bloomberg, June 5, 2014.

3 Bullard, James. “QE2: An Assessment.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, June 30, 2011.

4 More specifically, the lending facility has two parts. First, banks are allowed to borrow up to an amount equivalent to 7 percent of their nonfinancial private sector loans excluding mortgage loans outstanding as of April 30, 2014. Second, between March 2015 and June 2016 banks will be allowed to borrow up to three times their quarterly net lending (outlays minus repayments) to the eurozone nonfinancial sector excluding mortgages. Siedenburg, Kristian. “ECB Monthly Bulletin Editorial for June (Text).” Bloomberg, June 12, 2014.

5 Grimm, Christian; and Blackstone, Brian. “Draghi Says ECB Still Unlikely to Engage in Quantitative Easing.” The Wall Street Journal, April 28, 2014.

Additional Resources

- Regional Economist: The Effectiveness of QE2

- On the Economy: Youth Unemployment Notably High in Southern Europe

- On the Economy: Changes in Fed Communications in Recent Years

Citation

Alejandro Badel, ldquoRecent ECB Policy and Inflation Expectations,rdquo St. Louis Fed On the Economy, Aug. 4, 2014.

This blog offers commentary, analysis and data from our economists and experts. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Email Us

All other blog-related questions