Is College Still Worth It? The New Calculus of Falling Returns

Abstract

The college income premium is the extra income earned by a family whose head has a college degree over the income earned by an otherwise similar family whose head does not have a college degree. This premium remains positive but has declined for recent graduates. The college wealth premium (extra net worth) has declined more noticeably among all cohorts born after 1940. Among families whose head is White and born in the 1980s, the college wealth premium of a terminal four-year bachelor's degree is at a historic low; among families whose head is any other race and ethnicity born in that decade, the premium is statistically indistinguishable from zero. Among families whose head is of any race or ethnicity born in the 1980s and holding a postgraduate degree, the wealth premium is also indistinguishable from zero. Our results suggest that college and postgraduate education may be failing some recent graduates as a financial investment.

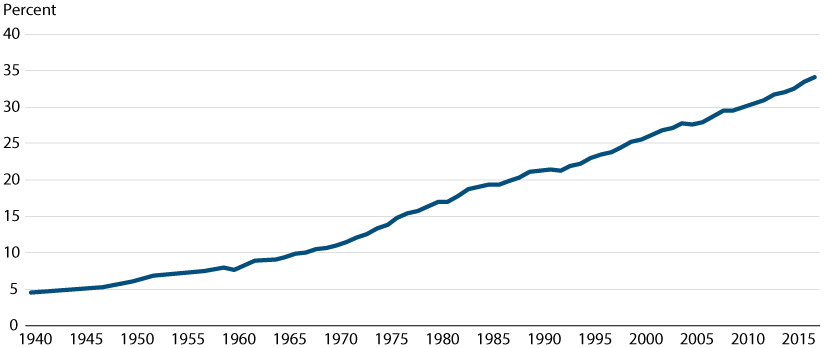

Having a four-year college degree is associated with many positive outcomes, including higher income and wealth, better health, a higher likelihood of being a homeowner and of being partnered (married or cohabiting), and a lower risk of becoming delinquent on any obligation (Table 1, Panel A). Among college graduates, families headed by someone who completed a postgraduate degree fare even better on these and other measures than families with a head with only a bachelor's degree (Table 1, Panel B). The fact that an increasing share of the adult population is completing four years or more of college suggests a widespread belief that college is, indeed, worth it (Figure 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of Families in the 2016 SCF by Education Level

Figure 1: Share of U.S. Population (25 Years+) That Completed 4+ Years of College, 1940-2017

NOTE: Between 1992 and 2017, the number of college graduates 25 years of age or older increased by 40 million, while the total number of people 25 years of age or older increased by 56 million. Thus, the net increase in college grads constituted 71 percent of total net population growth among people 25 years of age or older.

SOURCE: Census Bureau and authors' calculations.

Yet signs have emerged that the economic benefits of college may be diminishing. Despite large income and wealth advantages enjoyed on average by families with a head with a bachelor's degree or higher over families with a head without a postsecondary degree, recent cohorts of college graduates appear to be faring less well than previous generations.

We use the Federal Reserve Board's Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which covers family heads born throughout the twentieth century, to determine whether the economic and financial benefits of obtaining a postsecondary degree have changed over time. Our evidence is mixed but discouraging on balance. The income advantage of recent college graduates remains positive but may have declined for some demographic groups relative to older graduates. Meanwhile, the wealth-building advantage of higher education has declined among recent graduates of all demographic groups. Among all racial and ethnic groups born in the 1980s, only the wealth premium for White four-year college graduates remains statistically significant. Thus, we identify a striking divergence between the income and wealth outcomes of college graduates across birth cohorts.

Our findings highlight the fact that income and wealth measures, while related, are distinct and may provide different insights into college and postgraduate experiences. We suggest three potential explanations, each of which may contribute something to the patterns we identify:

- The luck of when you were born, since beginning to save and accumulate wealth at a time when asset prices (stocks, bonds, and housing) are high makes subsequent rates of return low and vice versa

- Financial liberalization, which may have created more opportunities for people born in the 1980s than in the 1940s, for example, to use (and misuse) credit when they were young, affecting their wealth but not their incomes

- The rising cost of higher education, which would not reduce college graduates' incomes but would reduce their wealth, at least early in life

Citation

William R. Emmons, Ana Hernández Kent and Lowell R. Ricketts,

ldquoIs College Still Worth It? The New Calculus of Falling Returns,rdquo

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Review,

Fourth Quarter 2019, pp. 297-329.

https://doi.org/10.20955/r.101.297-329

Editors in Chief

Michael Owyang and Juan Sanchez

This journal of scholarly research delves into monetary policy, macroeconomics, and more. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System. View the full archive (pre-2018).

Email Us