An Empirical Economic Assessment of the Costs and Benefits of Bank Capital in the United States

Abstract

We evaluate the economic costs and benefits of bank capital in the United States. The analysis is similar to that found in previous studies, though we tailor it to the specific features and experience of the U.S. financial system. We also make adjustments to account for the impact of liquidity- and resolution-related regulations on the probability of a financial crisis. We find that the level of capital that maximizes the difference between total benefits and total costs ranges from just over 13 percent to 26 percent. This range reflects a high degree of uncertainty and latitude in specifying important study parameters that have a significant influence on the resulting optimal capital level, such as the output costs of a financial crisis or the effect of increased bank capital on economic output. Finally, the article discusses a range of considerations and factors that are not included in the cost-benefit framework that could have a substantial impact on estimated optimal capital levels.

Introduction

We perform an economic analysis of the long-term costs and benefits of different levels of system-wide bank capital and estimate optimal Tier 1 capital levels under a range of modeling assumptions. Within our framework, the benefit of bank capital is to reduce the probability of costly future financial crises. The marginal benefit of bank capital generally decreases as capital levels rise; the potential improvement from reducing the frequency of crises becomes more limited as the frequency of crises approaches zero. The aggregate economic costs of bank capital stem from an increase in banks' cost of capital. This increase is passed on to borrowers in the form of higher credit costs and lowers gross domestic product (GDP). In our framework, the marginal cost of bank capital is constant.

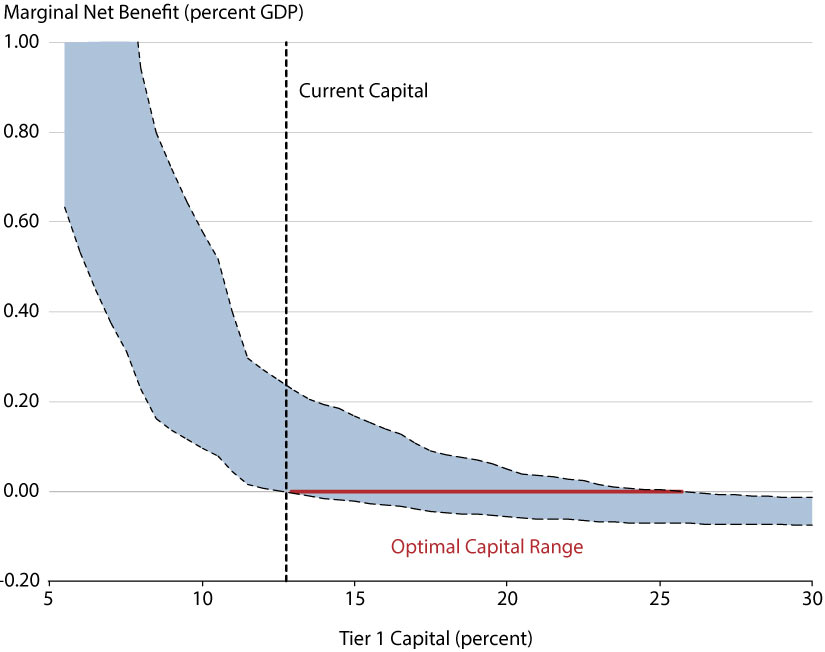

Figure 1: Estimates of the Net Benefits of Additional Tier 1 Capital (Marginal Net Benefits of Capital)

The shaded region in Figure 1 shows a range for our estimated marginal net benefits of capital. At levels of capital up to about 13 percent, the shaded region lies above the horizontal axis. This implies that our estimated range for the benefits of additional capital remains positive until Tier 1 capital ratios reach 13 percent. For levels of capital between 13 percent and 26 percent, the shaded region overlaps the horizontal axis. This overlap implies that our estimated benefits of additional capital for this range may be positive or negative, depending on the modeling assumptions used.

The width of the shaded region in the plot represents uncertainty around our estimates of the costs and benefits associated with the level of bank capital. The upper bound of this region represents our low estimate of the costs and high estimate of the benefits of bank capital. Specifically, it assumes that the effects of financial crises are permanent and that banks pass only 50 percent of capital-related cost increases on to borrowers. The lower bound of this region represents our high estimate of the costs and low estimate of the benefits of bank capital. Specifically, it assumes that the effects of crises diminish gradually over time and that banks pass all capital-related cost increases on to borrowers. We note that this plot shows levels of actual capital rather than minimum required capital. Because banks generally hold a buffer above and beyond the minimum required capital, we expect that optimal minimum capital requirements may be a bit below the range shown in Figure 1.

There is an extensive literature on financial crises in advanced economies and the relationship between bank capital and macroeconomic risk. Our methodology builds on studies by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2010), Brooke et al. (2015), and the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2016). All studies use the same basic framework; the effects of increased bank capital on the probability and severity of a crisis are compared with the increase in the cost of credit and associated reduction in GDP level. The BCBS (2010) study uses a meta-analysis of the academic literature, combined with results from various country-specific supervisory models, to quantify these effects. Brooke et al. (2015) and the Minneapolis Fed (2016) use both the existing literature and substantial original data analysis for calibration to the U.K. and U.S. economies.

Our approach differs from these studies in some significant ways. For example, we use adjustments and controls to account for the effects of new liquidity requirements and resolution requirements for failing firms. We also use Romer and Romer's (2015) generalized least squares (GLS) estimates of the severity of financial crises to reduce the result's dependence on data from inherently more volatile and smaller economies that are arguably less relevant to the United States. We provide estimates of the severity of financial crises that assume permanent effects of financial crises on GDP, as well as alternative estimates that assume persistent but decaying effects. Finally, unlike the BCBS (2010) and Brooke et al. (2015) studies, we design the research to ensure, where possible, that the analysis is tailored to the specific features of the U.S. financial system so that the results are relevant for considering capital regulatory policy in the United States. Our results imply larger optimal capital levels than those in Brooke et al. (2015) and similar levels to those in the BCBS (2010) and Minneapolis Fed (2016) studies. Like past studies, our framework addresses broad changes in capital rather than targeted requirements that apply to specific banks, such as the global systemically important banks (GSIBs) surcharge and the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR). Our framework assumes that all banks choose the same capital ratios, and we do not account for the heterogeneity of the U.S. capital framework resulting from targeted regulations.

Citation

Simon Firestone, Amy Lorenc and Ben Ranish,

ldquoAn Empirical Economic Assessment of the Costs and Benefits of Bank Capital in the United States,rdquo

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Review,

Third Quarter 2019, pp. 203-30.

https://doi.org/10.20955/r.101.203-30

Editors in Chief

Michael Owyang and Juan Sanchez

This journal of scholarly research delves into monetary policy, macroeconomics, and more. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System. View the full archive (pre-2018).

Email Us