Understanding Lowflation

Abstract

Central banks are viewed as having a demonstrated ability to lower long-run inflation. Since the Financial Crisis, however, the central banks in some jurisdictions seem almost powerless to accomplish the opposite. In this article, we offer an explanation for why this may be the case. Because central banks have limited instruments, long-run inflation is ultimately determined by fiscal policy. Central bank control of long-run inflation therefore ultimately hinges on its ability to gain fiscal compliance with its objectives. This ability is shown to be inherently easier for a central bank determined to lower inflation than for a central bank determined to accomplish the opposite. Among other things, the analysis here suggests that for the central banks of advanced economies, any stated inflation target is more credibly viewed as a ceiling.

Introduction

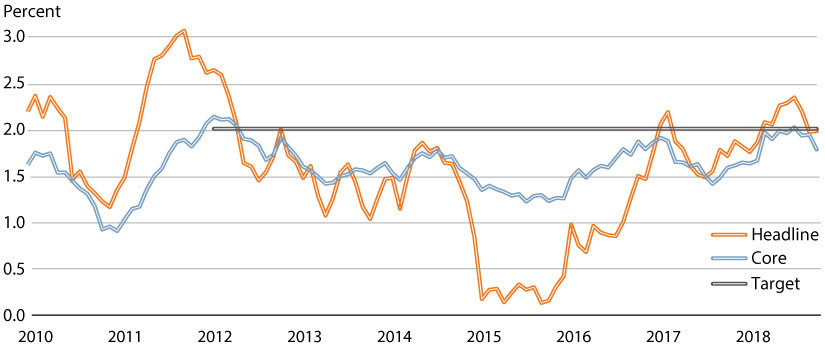

Inflation has remained stubbornly below target in many countries since the Financial Crisis of 2008, a phenomenon that the International Monetary Fund has aptly labeled "lowflation." In the United States, this is especially evident since 2012—ironically, the year the Federal Reserve adopted an official 2 percent personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation target. As shown in Figure 1, both core and headline measures of PCE inflation have remained persistently and significantly below a supposedly symmetric target.

Figure 1: PCE Inflation, January 2010—October 2018

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

A puzzling aspect of this recent lowflation episode is that by many measures, Federal Reserve policy has been perceived to be unusually "accommodative." The effective federal funds rate, for example, averaged roughly 10 basis points over the period 2009-15. Over the period 2008-14, the liabilities of the Federal Reserve increased from less than $1 trillion to roughly $4.5 trillion.

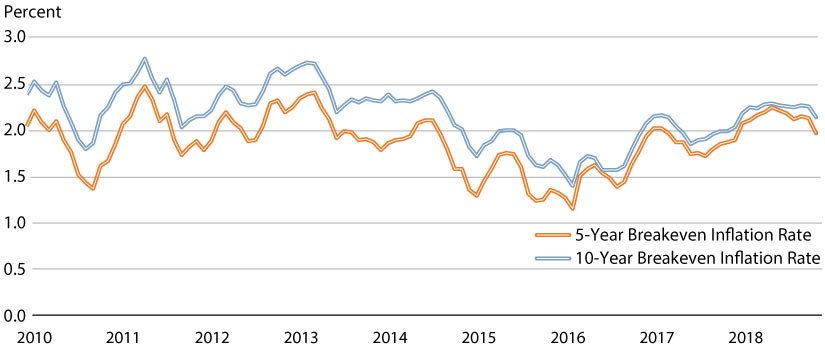

The puzzle is further compounded when viewed through the lens of the Phillips curve theory of inflation. That is, after peaking at 10 percent in 2009, the civilian unemployment rate in the United States declined steadily to approximately 4 percent today. Conventional wisdom suggests that a low unemployment rate should portend higher future inflation. And yet, as shown in Figure 2, measures of inflation expectations have, if anything, declined since 2010.

Figure 2: Market-Based Inflation Expectations, January 2010—November 2018

SOURCE: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (BOG).

What is going on here? Isn't high inflation supposed to be easy to get? Didn't Zimbabwe give us a modern day lesson in creating inflation? Isn't Venezuela providing us the lesson in real time? Didn't former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker demonstrate how a sufficiently determined central bank can lower inflation? If so, then why does it appear so difficult for Federal Reserve officials to accomplish the reverse today?

We address these questions using a monetary-fiscal theory of inflation that is based on an overlapping-generations model in the spirit of Diamond (1965). The model features physical capital investment and an outside asset consisting of nominal government debt that can take the form of money (in the form of interest-bearing reserves) and bonds. The fiscal authority determines the path of government spending and taxation—and hence, the path of the nominal debt. The monetary authority determines the nominal interest rate paid on reserves and government debt—and hence, implicitly, the composition of the outstanding government debt between central bank reserves and government bonds in the hands of the public outside the central bank. Monetary and fiscal policy can have a persistent (even permanent) effect on the level of investment and output.

Control of the monetary aggregate in our model translates into control over the long-run inflation rate. Despite this "monetarist" aspect of our model, the central bank cannot unilaterally dictate the long-run inflation rate. The central bank can, however, determine the path of the price level (and hence, inflation) in the short run by manipulating the yield on bonds via open market operations when reserves are scarce and via the interest paid on reserves when reserves are held in excess of the statutory minimum. The real effects of monetary policy in the model are consistent with conventional views of the monetary transmission mechanism.

We use our model to identify what, if any, limits are faced by a monetary authority intent on pursuing a long-run inflation policy in the face of an uncooperative fiscal authority. We consider two thought experiments. Both experiments begin with the economy in a stationary state where the bond yield is higher than the interest paid on reserves (so that reserves are scarce) and where both the monetary and fiscal authorities agree on a long-run inflation target. Fiscal policy is "Ricardian" in the sense that, for any given monetary policy, the intertemporal government budget constraint is satisfied through adjustments in the real primary budget surplus. In the first thought experiment, the central bank suddenly lowers its preferred long-run inflation target, trying to keep inflation at the lower rate for as long as it can. In the second thought experiment, the opposite is considered—the central bank suddenly raises its preferred inflation target. The central issue is how the resulting conflicts are likely to be resolved in the long run. Our analysis suggests that a central bank is more likely to win the first contest and lose the second.

Despite the conventional "monetarist" flavor of our model, there are two reasons why a central bank may not have unilateral control over the long-run inflation rate. First, central banks are normally constrained to create money out of Treasury securities. They are not typically allowed to engage in monetary transfers (helicopter drops) or to tax. Because this is so, the supply of central bank money cannot grow more rapidly than the public debt for an indefinite period. Second, the relevant monetary base may at times include the total public debt and not just the fraction of it monetized by a central bank. When central bank reserves and Treasury securities are viewed as close substitutes (as evidenced, for example, by a small spread on their respective yields), then the effective base money supply constitutes the total supply of outside assets—an object that is controlled by the fiscal authority rather than the monetary authority.

Despite these restrictions, a central bank need not be completely impotent in terms of influencing the price level and even the eventual path of long-run inflation. Under normal conditions (i.e., when bonds dominate money in rate of return), the central bank of our model can influence real economic activity and the price level through open market operations. Although our central bank cannot determine the long-run inflation rate without fiscal cooperation, it can influence the path of the price level for at least a finite period of time. Over the course of this finite time interval, the central bank pressures the fiscal authority along two dimensions. First, in an attempt to, say, lower inflation through a restrictive monetary policy, the central bank depresses real economic activity. Second, the implied higher interest rate associated with tight monetary policy has the effect of increasing the interest expense of the public debt, necessitating politically painful fiscal adjustments.

The idea we promote below is reminiscent of Wallace's "game of chicken," which Sargent (1986) used as an interpretation of the Reagan deficits. In that interpretation, the administration cut taxes and encouraged tight monetary conditions to induce Congress to cut spending. As we explain below, our reading of the evidence suggests rather less cooperation between the Federal Reserve and the administration, with elements of Congress divided between them. Nevertheless, the implications of our game vis-a-vis the Wallace game appear to be the same; in particular,

While the authorities are playing this game of chicken, we would observe large net-of-interest government deficits, low rates of monetization of government debt (low growth rates for the monetary base), and maybe also high real interest rates on government debt. (Sargent, 1986, pg. 10)

Of course, back in the 1980s, the issue of monetary-fiscal coordination was discussed in the context of a high-inflation environment. Proponents of central bank independence frequently cast the scenario as the need for a sober and committed monetary authority to check a naturally profligate fiscal authority (Waller, 2011). Because high inflation is almost always the problem, few thought to ask what a policy coordination game might look like in the context of lowflation.

Our theory of inflation suggests the pressure that a central bank can bring to bear on the fiscal authority—and hence, the leverage it has to ultimately sway the course of fiscal policy—is asymmetric across high versus low inflation regimes. In the former case, lowering inflation requires a contractionary monetary policy that, among other things, increases the interest expense of the public debt. In the latter case, increasing inflation requires an expansionary monetary policy which, as a side benefit, lowers the interest expense of the public debt. Moreover, when expansionary monetary policy takes the form of Treasury purchases, the nominal interest rate can fall only as low as the interest paid on reserves. Central bank purchases of Treasury securities become increasingly ineffectual as the spread on bond yields and reserves narrows. In the limit, when they are equal, further asset purchases are inconsequential except insofar as they result in a buildup of excess reserves.

Citation

David Andolfatto and Andrew Spewak,

ldquoUnderstanding Lowflation,rdquo

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Review,

First Quarter 2019, pp. 1-26.

https://doi.org/10.20955/r.101.1-26

Editors in Chief

Michael Owyang and Juan Sanchez

This journal of scholarly research delves into monetary policy, macroeconomics, and more. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System. View the full archive (pre-2018).

Email Us