Freshwater Scarcity Risk Rises in the U.S. and Eighth District

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- While fresh water was once considered an abundant resource, scarcity issues are rising nationally and regionally.

- Higher temperatures, changing precipitation patterns and urbanization play a role, as does aging infrastructure.

- In the Fed’s Eighth District, groundwater scarcity is of notable concern in Arkansas, where water-intensive agriculture is prominent.

In the 1746 edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack, Benjamin Franklin quipped, “When the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”Benjamin Franklin often shared the wise words of others in his Almanack. The quotation may have been published first by English author Thomas Fuller in his 1732 volume, “Gnomologia: Adagies and Proverbs.” Two hundred seventy-five years later, the U.S. that Franklin helped found is now facing that proverbial dry well as regions of the country experience climate change-induced temperature extremes and changing precipitation patterns.

A record-breaking heat wave in the early summer of 2021 has already seared the western and southwestern U.S., exacerbating a deep long-term drought. Drought is also affecting the High Plains and upper Midwest. Meanwhile, demand for fresh water has risen because of population growth and increased usage from agricultural and industrial sectors that rely on consistent access to plentiful supplies.

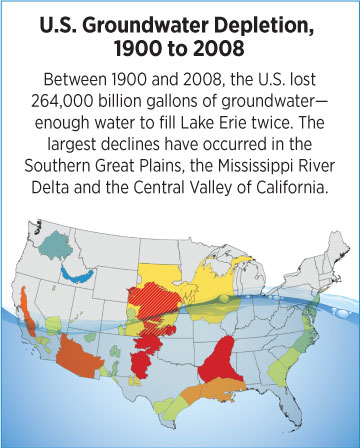

SOURCES: Circle of Blue and U.S. Geological Survey.

NOTES: Parts of the map in red show the most

groundwater depletion in cubic kilometers.

Orange is next-highest, followed by yellow.

Growing freshwater scarcity risk in the U.S. and the world is revealing the need for more optimal mechanisms for allocating water. Fresh surface water from rivers, lakes and reservoirs, as well as fresh groundwater in aquifers, has long been seen as limitless, and as a result, has been far undervalued. This undervaluation has led to misallocation and overuse.

For example, the combination of diminishing precipitation and rising demand has caused U.S. aquifer levels to decline more quickly than can be naturally replenished. Misallocation of water also has led to inadequate investments in U.S. water infrastructure, which is crumbling. Leaks alone cause 2.1 trillion gallons of water to be lost each year (PDF), according to the U.S. Water Alliance. Misallocation has also hindered the development of new water technologies and led to an increasing number of water-rights lawsuits before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Water Futures

One recent harbinger of the need to better determine water’s value was the launch of the first water futures contract by the CME Group and the Nasdaq stock exchange on Dec. 7, 2020. The contract represents the first regulated, exchanged-traded risk management tool for water. It allows participants from the agricultural, commercial, municipal water and insurance industries to hedge their future price risk by buying or selling water contracts based on the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index (NQH20).

The index and corresponding futures contract have surged since late March, when it first became evident that winter snows and rain were not falling in enough quantity to recharge mountain snow packs and replenish freshwater supplies typically found in rivers, reservoirs, lakes and streams in the western U.S.

While California market participants can use the futures contract to hedge their specific risks, an increasing number of financial institutions, real estate investors and others are adding water scarcity risk to their portfolio assessments. For example, the BlackRock Investment Institute found that close to 60% of the global real estate investment trust (REIT) properties it was able to examine will experience high water stress by 2030. That’s more than double today’s number.

Freshwater Basics

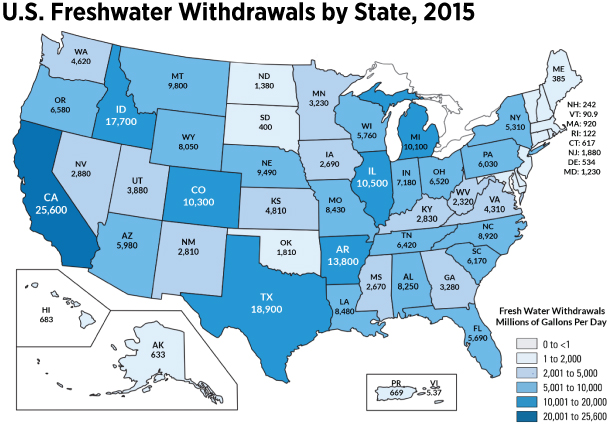

In 2015, the U.S. used an average 281 billion gallons of freshwater a day (Bgal/day), sourced from surface water and groundwater, according to the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2015.

Fresh surface water withdrawals averaged 198 Bgal/d in 2015, down 14% from 2010. Fresh groundwater withdrawals were 82.3 Bgal/day, up 8% from 2010.

Agricultural irrigation constituted 37% of total freshwater withdrawals, while thermoelectric usage accounted for 41%. Domestic and private usage comprised 14%; commercial and industrial usage, 6%; and livestock and aquaculture usage, 3%.

Stressed Out

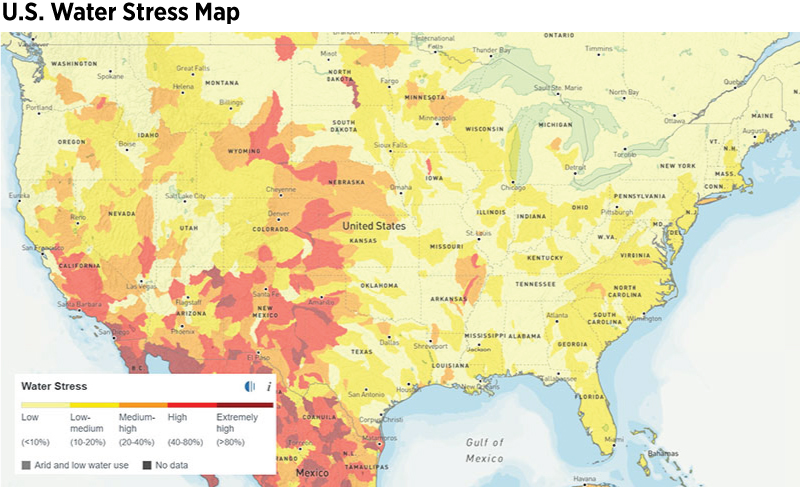

The World Resource Institute’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas uses hydrological models and more than 50 years of data to estimate the typical water supply compared with demand. The water stress scale shows regions that are coming close to draining their annual water stores in a typical year. As shown below, water stress reaches into many regions of the U.S., including portions of states in the Eighth Federal Reserve District.The Eighth District includes all of Arkansas, eastern Missouri, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, western Tennessee and northern Mississippi.

Arkansas, which is in the Eighth District, is the fourth-largest user of fresh water overall and the second-largest user of groundwater after California. Arkansas uses groundwater for most of its agricultural needs, including the controlled flooding of its rice crops. Arkansas is the country’s top rice-producing state, with 40% of the U.S. crop. It also irrigates its cotton crops; in 2020, Arkansas was the third-largest cotton-producing state.

Crop production is concentrated in the eastern half of Arkansas, which is where the state’s aquifers are under the most strain, according to the Arkansas Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Division. In its latest Arkansas Groundwater Protection and Management report, the division notes that withdrawals of groundwater are happening at an unsustainable rate. The report focuses on two critical but stressed aquifers that support eastern Arkansas as well as portions of Missouri, Tennessee and Mississippi: the Mississippi River Valley Alluvial Aquifer and the Sparta-Memphis Sand Aquifer (also known as the Middle Claiborne Aquifer).

Battles Erupt over Scarce-Resource Allocation

The Sparta-Memphis Sand Aquifer is also the focus of a potentially precedent-setting case before the U.S. Supreme Court. In its case against Tennessee, Mississippi claims that the city of Memphis has been pumping water from the aquifer so extensively that a depression has formed in the water table beneath the city’s wells.

The Memphis area is one of the largest metropolitan areas in the world that relies exclusively on groundwater for municipal use. Mississippi is seeking $615 million in compensation from Tennessee. While the Supreme Court has heard interstate surface water cases in the past, this is its first interstate groundwater case. In November 2020, a U.S. Supreme Court special judge concluded that water in the aquifer can’t be confined within one state’s borders and must be shared. The high court is expected to rule on the judge’s recommendation by mid-2021 and its decision may influence groundwater management for decades.

The number of interstate legal battles involving water usage is expected to grow as water scarcity issues rise. In April 2021, a 20-year battle was settled when the Supreme Court ruled that Florida did not prove Georgia’s use of the Chattahoochee River caused Florida’s oyster fisheries to collapse.

Conclusion

The availability of, and access to, fresh water is at risk as demand begins to threaten supply in many regions of the country and the world. Temperatures are rising, reservoirs are receding and aquifers are shrinking. Infrastructure is crumbling, while crops are withering in the western and north-central U.S. Interstate battles over fresh water are on the rise and the financial sector, along with central banks and other regulators, is paying increased attention to water—either as part of deliberations about climate change and environmental, social and corporate governance issues—or as a major risk in its own right.

In the meantime, there is a growing focus on conservation and water recycling methods, including some efforts to recharge aquifers. Scientists and ag-tech startups are developing crops that are less water-dependent, and farmers are using methods to help soil retain more moisture and nutrients. Desalination companies are developing better technologies to generate sources of fresh water from salt water, while others are generating fresh water from the air.

On the water infrastructure front, in late April 2021, the U.S. Senate passed a bipartisan bill authorizing more than $35 billion to upgrade states’ water infrastructure. If approved by the House and signed into law, the Drinking Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Act will give the Environmental Protection Agency funding for grant programs and revolving loan funds to help upgrade aging infrastructure, invest in new technologies and support disadvantaged communities.

While the American Society of Civil Engineers and the Value of Water Campaign estimate that it will take more than $3 trillion to fully fund U.S. water infrastructure needs over the next 20 years, the bill is a first step forward. From conservation, to innovative technology, to fixing leaky pipes, all are growing more essential to ensuring a robust water supply for generations to come.

Endnotes

- Benjamin Franklin often shared the wise words of others in his Almanack. The quotation may have been published first by English author Thomas Fuller in his 1732 volume, “Gnomologia: Adagies and Proverbs.”

- The Eighth District includes all of Arkansas, eastern Missouri, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, western Kentucky, western Tennessee and northern Mississippi.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us