Moving In, Moving Out: The Migration Pattern of the Eighth District

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Population growth is an important component of economic growth. Migration is one way that a community can increase its population.

- From 2013 to 2017, migration helped some metro areas in the Eighth District, but its overall effect on the population of the District states was relatively small.

- During that time, the educational attainment and income of people moving into the District states were slightly lower than those of people leaving.

Population growth is an important component of economic growth. An increase in the population means more workers in the labor market. It also brings more potential customers for products and services. Moreover, a steady increase in the population helps maintain a healthy age structure between workers and retirees that is needed for a sustainable public pension system.

However, the U.S. population growth rate has been declining in recent years. Between 2017 and 2018, the population grew only 0.62%—the country’s lowest growth rate in 80 years.See Frey.

This slowdown in population growth could be a drag on overall economic growth and could cause firms to curtail expenditures on capital investment for future production. Some economists argue that an aging population contributes to a long period of low economic growth, more commonly referred to as secular stagnation.See the Economist.

There are several factors that drive population growth. Besides the natural birth and death rates, migration also plays an important role. Recent debates in the media focus on migration across countries but tend to ignore migration at the state and county levels within the U.S.

In this article, we provide an overview of the migration patterns of the Eighth Federal Reserve DistrictHeadquartered in St. Louis, the Eighth Federal Reserve District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee. from 2013 to 2017. We analyze migration patterns both into and out of select metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) within the Eighth District and into and out of the states that make up the District as a whole. We also examine the demographics of individuals moving into and out of the District.

Measure of Migration

Individual migration data are calculated from the American Community Survey (ACS) five-year sample released in 2019, which covers 2013 to 2017. The five-year ACS data are a 5% sample of the U.S. population, covering more individuals than the ACS’s typical annual 1% sample. Microdata for the ACS are accessed from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS). We define migration as movement to a different home within a state, between states or from abroad.

In our analysis, we first calculated the total migration flows of 10 select District MSAs.In this context, people who move from one residence to another within the same MSA are not counted since they are not migrating into or out of that metro area. Conversely, those who move from a residence outside the MSA to one inside of it (or vice versa) are counted, regardless of whether the migration occurs entirely within the Eighth District. For example, movement to Columbia, Mo., from Memphis, Tenn., would be counted as migration in the MSA-level analysis, but this movement would be excluded in the District-level analysis since that movement is neither into nor out of the District. Next, we calculated the Eighth District’s total migration flows and the demographics of those flows. For the purpose of this article, we looked at state-level data for the District states (Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee) rather than the data for only the parts of those states that lie within the District’s boundaries.

Migration by District MSA

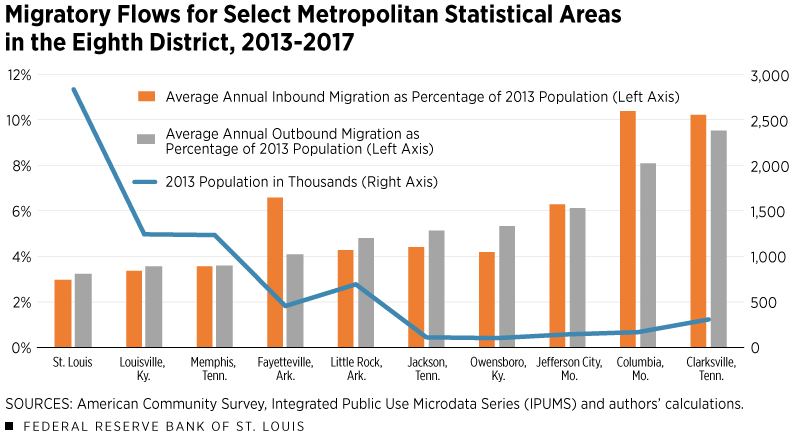

The accompanying figure presents the migration patterns for the selected District MSAs. The figure shows the total population size in 2013 (on the right axis) and the average annual migration rate in and out of the MSAs between 2013 and 2017 (on the left axis).

Among these metros, the Clarksville, Tenn., MSA experienced the highest turnover rate between 2013 and 2017: Relative to its population size in 2013, 10.2% moved into the MSA annually on average, while 9.5% moved out.We use the annual 1% ACS for 2013 from IPUMS to calculate 2013 population data at the MSA level. It is likely that Clarksville’s high migration rates as a percentage of its total population are due to its small size and proximity to a military base—Fort Campbell. Similarly high rates are also found in college towns: Columbia is home to the University of Missouri, and Fayetteville is home to the University of Arkansas. Meanwhile, the St. Louis MSA saw the smallest turnover in population, with 3.0% moving in and 3.2% moving out annually on average.

Both the Fayetteville, Ark., MSA and the Columbia, Mo., MSA benefited the most from the net influx from migrations. The average annual net increase from migration was equal to 2.5% and 2.3% of the 2013 population in these MSAs, respectively. For the rest of the MSAs, the inflows and outflows were roughly the same.

Migration by Demographics

With the individual-level data, we can decompose the migration flows by characteristics. (See table below.) One important aspect to consider is age. As mentioned above, the age structure affects the economy through the channel of labor supply and consumption-saving decisions.

| People Moving into District | People Moving out of District | Net Migration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Younger than 16 | 148,405 | 137,792 | 10,613 |

| 16-24 | 208,374 | 182,631 | 25,743 |

| 25-34 | 210,722 | 187,211 | 23,511 |

| 35-64 | 240,898 | 221,579 | 19,319 |

| 65+ | 59,052 | 57,051 | 2,001 |

| Education | |||

| High School or Less | 459,023 | 397,981 | 61,042 |

| Some College | 153,948 | 147,360 | 6,588 |

| College Plus | 254,480 | 240,923 | 13,557 |

| Median Wage and Salary Income | $36,197 | $37,880 |

SOURCES: American Community Survey, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) and authors' calculations.

Using District states as the unit of analysis, we found that net migration into the District is positive, though it accounts for a very small fraction of the total population.

We then broke down migration flows into five different age groups: younger than 16, 16-24, 25-34, 35-64, and 65 and older. The age group of 35 to 64 had the largest annual migration average into and out of the District, while the 65-plus group had the smallest. We saw some differences in the annual migration averages across the age groups, but the net flows into and out of the District were mostly the same.

Next, we examined the migration pattern by level of education attained. We divided the sample into three groups: high school or less, some college, and college plus. We define high school or less as those whose last grade completed was 12 or less, some college as those with one to three years of higher education, and college plus as those with four years or more of higher education.

While net migration for all three education groups was positive, our analysis showed notable differences in inbound and outbound migration. Among people with some college or college plus, those moving in roughly equaled those moving out. For people with high school or less, however, those moving in noticeably outnumbered those moving out.

Finally, we looked at the migration by income groups, measuring income on the individual level by using wage and salary income earned in the year before migration (inflation-adjusted to 2017 values). We found that there was a difference between the income of people entering the District and the income of those leaving. The median income of people moving in was $36,197, while the median income of people moving out of the District was $37,880. This difference could be attributed to the education level of migrants (as mentioned above), since people with some college or college plus have higher income on average.

Conclusion

The size of the District’s population did not change much due to migration between 2013 and 2017. Some MSAs, like Fayetteville and Columbia, benefited from the net migration.

Inbound and outbound migration flows exhibited different socio-economic characteristics. People lacking any college education made up a larger proportion of those moving into the District (52.9%) than those moving out (50.6%). Those moving out of the District also earned a slightly higher income than those moving into the District.

Devin L. Werner, a research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, provided research assistance.

Endnotes

- See Frey.

- See the Economist.

- Headquartered in St. Louis, the Eighth Federal Reserve District includes all of Arkansas and parts of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee.

- In this context, people who move from one residence to another within the same MSA are not counted since they are not migrating into or out of that metro area. Conversely, those who move from a residence outside the MSA to one inside of it (or vice versa) are counted, regardless of whether the migration occurs entirely within the Eighth District. For example, movement to Columbia, Mo., from Memphis, Tenn., would be counted as migration in the MSA-level analysis, but this movement would be excluded in the District-level analysis since that movement is neither into nor out of the District.

- We use the annual 1% ACS for 2013 from IPUMS to calculate 2013 population data at the MSA level. It is likely that Clarksville’s high migration rates as a percentage of its total population are due to its small size and proximity to a military base—Fort Campbell. Similarly high rates are also found in college towns: Columbia is home to the University of Missouri, and Fayetteville is home to the University of Arkansas.

References

Economist. “What It Means To Suffer from Secular Stagnation.” March 8, 2015.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us