Observing the Earnings Gap through Marital Status, Race and Gender

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Married men make the most in annual earnings when marital status across gender and race (black and white) is examined, according to an analysis of census data.

- When comparing usual hours worked across workers, married men work the most hours out of all groups considered, though this difference is slight.

- Married white men make the most of all groups when annual earnings and hourly earnings are compared, and this difference is large.

The gender earnings gap is a well-known phenomenon. Perhaps less known is the fact that a significant portion of the gap is due to married men. In an Economic Synopses published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis in 2018, Guillaume Vandenbroucke highlighted the gap in earnings among married men on the one hand, and single men, single women and married women on the other hand.See Vandenbroucke, 2018.

The breadth of the inequality in earnings between married men and the other three groups is only one aspect worth noting, though. What is even more remarkable is that workers among the other three groups tend to maintain similar earnings over their respective life cycles.

For what follows, it is useful to distinguish between what we refer to as “earnings”—that is, the total labor income received by a worker—and what is often referred to as “wages”— that is, the earnings per hours worked, or the hourly wage. The two concepts are related by the following equation:

Earnings = (Hours Worked) × (Earnings per Hour)

Our aim in this article is twofold. First, it is to extend the earlier analysis to distinguish across races (namely white and black). A 2017 report at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco highlighted that the black-white wage gap remains important and “cannot be fully explained by differences in age, education, job type, or location.” Our goal is not to “further explain” or “better explain” the black-white wage gap, however; instead, it is to point out the importance of marital status when thinking about earnings inequality between genders and races.

Our second objective is to decompose the earnings gap into two elements: a gap in hourly wages and a gap in hours worked. Understanding the difference between earnings and wages is essential to our analysis, since the earnings of two workers may differ because of their hourly wage or the number of hours they work per week. We demonstrate that, although married men tend to work longer hours, most of the earnings gap is due to their larger hourly wage.

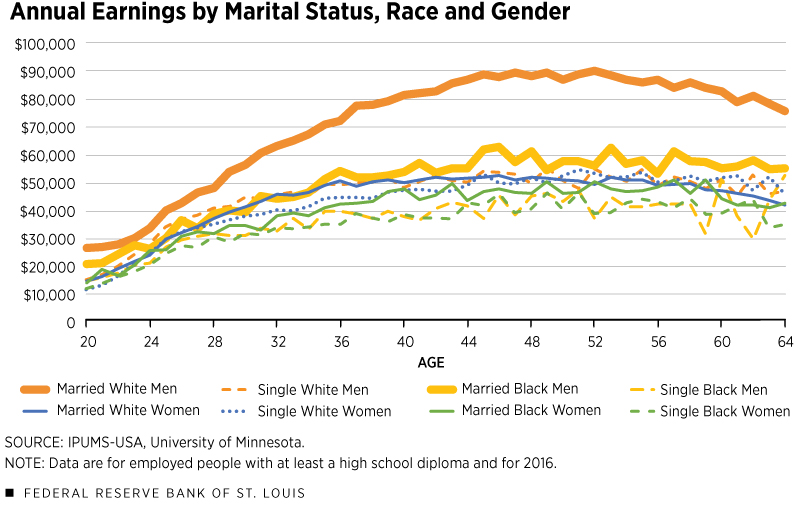

We use labor earnings data from the American Community Survey, collected through IPUMS-USA, for the census year 2016 among employed people between ages 20 and 64 with at least a high school diploma. Figure 1 shows the data by age for blacks and whites, singleIt is important to note that the category “single” refers to people who have never been married. We do not consider separated, divorced or widowed people in our analysis. and married, and males and females.

The first point of note in this figure is that earnings increase with age up to a certain point, across all groups. The second point is that married men (the orange and gold solid lines) are earning more than the other groups. Yet, even though married men are among the highest earners, there exists a great disparity in wages between married white men (with average earnings peaking at $90,000) and all other groups, including married black men (with average earnings peaking at $62,000), who tend to make only slightly more on average than the other groups. A final observation is that single black men and single black women earn the least across all groups.

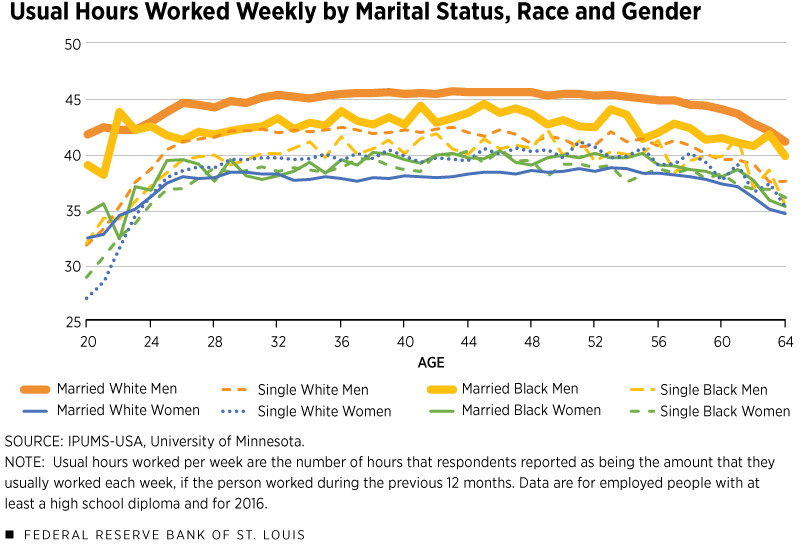

The earnings data plotted in Figure 1 are annual earnings. They comprise a combination of hours worked and hourly wages, as indicated earlier. In theory, therefore, it is possible that some workers receive higher earnings simply because they work longer hours. How much of the difference in annual earnings between married white males and the other groups is attributable to married white males working longer hours? To answer this question, we plot the usual hours worked per week by the same eight groups in Figure 2.Usual hours worked per week reports the number of hours per week that a respondent to the census questionnaire usually worked, if the person worked during the previous 12 months.

Figure 2 displays the average of usual hours worked per week by each group of workers and by the group’s age. Married white men work the longest hours, though the difference is slight, especially when compared to single white men and married black men.

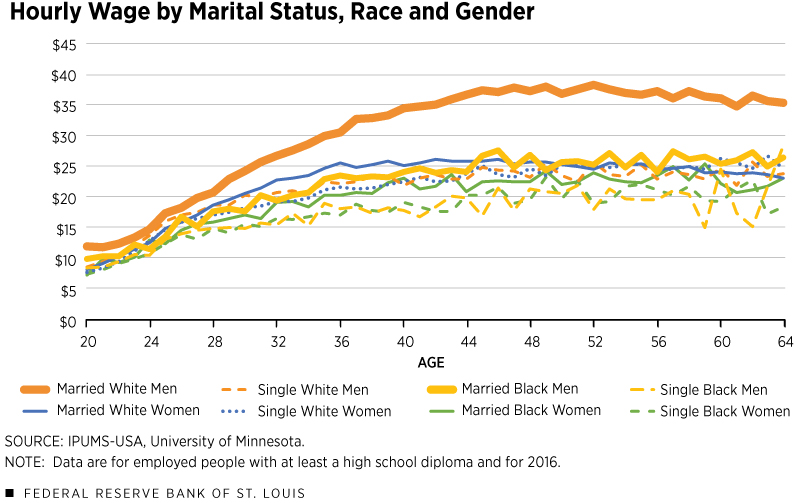

We use the data from figures 1 and 2 to build Figure 3, which plots hourly wages across the eight groups of workers. The first observation is that married white males are making significantly more per hour compared with the other groups. This, combined with their longer hours, explains why their annual earnings are so high.

The second observation is that with the exception of married white men, the groups make around the same amount of money per hour of work. Contrary to the message of Figure 1, which indicates that married men earn more than other groups, the hourly wages of black married men do not stand out. Third, single black men and women are compensated the least of the eight groups.

Though we are not offering an explanation of the earnings gap, our findings should be viewed as an attempt to point the broader scope of research, as well as the public debate, in a specific direction by asking, Why are married white men earning so much more than everyone else? The key word here is “married.” The analysis above shows that even though important differences in earnings among genders and races exist, the true outliers on the earnings scale are more evident by their marital status. In other words, Figure 3 shows that men and women do not differ much in their hourly wages provided they are single, and that black and white workers do not differ so much, provided they are married women.

It is important to note that although we are analyzing one year of data during which people are either single or married, it remains the case that one can choose to switch from single to married at some point in one’s lifespan.To be precise, it is possible that an individual can marry during the course of a single year. Though we chose to abstract this issue from our calculations, it is possible to restrict the sample to only married people who did not get married in the past year. Given this information, one may wonder whether such a choice (to move from one relational status to the next) subsequently implies that one (specifically white men) would start to earn more as a result of getting married.

In other words, does marriage make white men more productive? Or could it be that more-productive white men are more likely to marry than less-productive white men? Answers to these questions are beyond the scope of this paper, but answering them in the future will be useful for further understanding inequality in the U.S.

Endnotes

- See Vandenbroucke, 2018.

- It is important to note that the category “single” refers to people who have never been married. We do not consider separated, divorced or widowed people in our analysis.

- Usual hours worked per week reports the number of hours per week that a respondent to the census questionnaire usually worked, if the person worked during the previous 12 months.

- To be precise, it is possible that an individual can marry during the course of a single year. Though we chose to abstract this issue from our calculations, it is possible to restrict the sample to only married people who did not get married in the past year.

References

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us