Unequal Pink Slips? Gender and the Risk of Unemployment

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The U.S. jobless rate for women had been higher than that for men for more than three decades after World War II.

- Starting in the 1980s, the gender unemployment gap shrank.

- Women now appear to be less exposed to increased unemployment during recessions than men.

Men and women fare differently in the labor market. There is, for instance, a large literature documenting earning differences between men and women who work the same job and have comparable education and experience. Similarly, it is well-known that progression and promotion in the workplace often seem more difficult for women than for men.

In this article, we discuss another facet of the difference between men and women in the labor force: their exposure to unemployment. We complement our analysis with a discussion of the black-white exposure to unemployment and show that it behaves noticeably differently than male-female exposure.

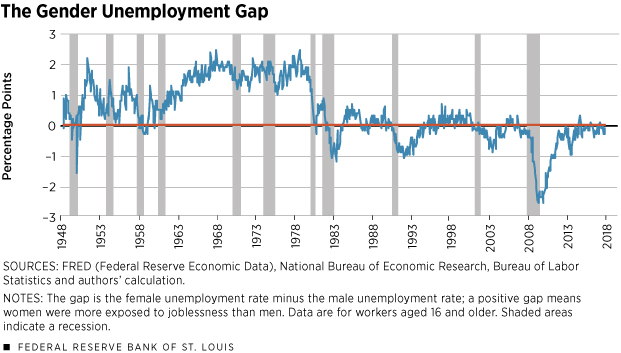

Figure 1 shows the difference between the unemployment rates of women and men since the late 1940s. We call this the “gender unemployment gap.” The shaded areas represent recessions dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

A few observations are worth noting. First, the gap tended to be positive before the 1980s; it was arguably large during the 1960s and 1970s, when the gap was between 1 and 2 percentage points. This means that for a long period of time, the unemployment rate of women was above that of men, i.e., women faced higher unemployment risk than men.

Second, throughout the 1980s and until the last recession, the gap was no longer as large as it had been. Instead, the gap seemed to hover just above or below zero, suggesting that women and men faced a similar risk of unemployment during this period.

Finally, the unemployment gap exhibits a tendency to decrease during recessions. This is particularly clear in the last recession. The unemployment rates of men and women were very close in the months leading up to the recession. In June 2007, for instance, the unemployment rate was 4.7 percent for men and 4.4 percent for women. But the unemployment rate of men rose to 11 percent in January 2010 versus 8.4 percent for women, causing a gap of almost –3 percentage points between them at the end of the recession.

The decline of the gender gap in the unemployment rate indicates that women appear to be less exposed to increased unemployment during recessions than men.

Changes in the Gender Gap during Recessions

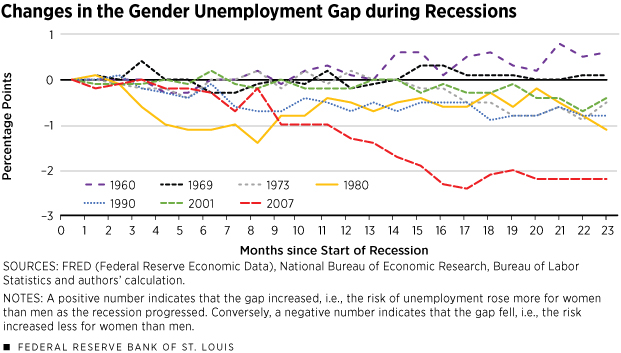

Changes in unemployment, which are large during recessions, can have important welfare consequences. But, how do recessions affect the unemployment gap? We address this question in Figure 2. To build this figure, we considered the last seven recessions identified by the NBER.We do not consider the recession that started in July 1981 since it is subsumed in the two-year period after the start of the recession that began in January 1980.

First, we collected the data on gender gap in unemployment that start with the beginning of each recession and end 24 months later. Then, to allow for an easy comparison between each of the seven series of numbers, we “normalized” the gap to zero at the beginning of each recession. This explains why the lines in Figure 2 all start at zero.

An example can help. Take the case of the 1980 recession. When the recession started in January 1980, the unemployment gap between men and women was 1.1 percentage points, i.e., the women’s unemployment rate was 1.1 percentage points higher than that of men. In May 1980, which was the fourth month after the start of the recession, the gap was 0.1 percentage point. Thus, the gap decreased by 1 percentage point. Hence, the –1 can be seen in Figure 2 at the fourth month after the start of the 1980 recession.

There are three groups of recessions that stand out in Figure 2. Consider first the 1960 and 1969 recessions. The unemployment gap did not decrease significantly; it remained positive or near zero for one to two years after the start of the recession. This confirms the first observation made about Figure 1, that is, women faced higher unemployment risk than men.

The second group comprises the recessions from 1973 to 2001. These recessions show an approximately 0.5 to 1 percentage point decrease in the unemployment gap two years after the start of the recession.

Finally, the Great Recession—that is, the 2007 recession—stands out. Like recessions from 1973 to 2001, the Great Recession was followed by a reduction in the unemployment risk of women relative to men. But the magnitude of the reduction is dramatically different: Two years after the start of the recession, the gender unemployment gap was about 2 percentage points lower. In summary, these post-1970 recessions imply a lasting reduction in the unemployment risk of women relative to men, but the last recession stands out in the magnitude of this reduction.

The Racial Gap

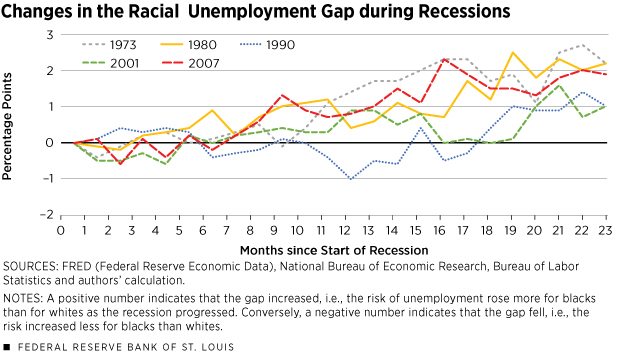

A similar analysis can be conducted across race instead of across gender. Figure 3 is analogous to Figure 2, but the gap analyzed there is the difference between black and white. A positive gap means that the black unemployment rate is higher than the white unemployment rate.Data for the black unemployment rate are not available for the 1960s.

The lesson from Figure 3 is remarkably different from that of Figure 2. First, the 2007 recession does not particularly stand out. Second, all the plotted recessions exhibit an increasing gap in the two years following the start of the recession. Black workers become relatively more exposed to unemployment than white workers after a recession.

Conclusion

We do not have a theory of the different patterns exhibited across recessions in Figure 2. Similarly, we do not have a theory of the difference between Figure 2 and Figure 3. We have documented the patterns of these gaps, but an explanation of these patterns is beyond the scope of our article. Yet the patterns raise important questions. Why are women relatively less exposed to the unemployment risk after recessions? Why are black workers relatively more exposed? Why does the Great Recession appear so different for the gender gap but not the race gap? Further research aimed at explaining these patterns would be of great interest.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us