Handle with Care: Report on GDP for First Quarter

The U.S. economy registered weaker-than-expected growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of the year, eking out a gain of 0.7 percent at an annual rate. Normally, such a tepid pace of growth would be cause for alarm among the forecasting community. However, few if any forecasters are sounding the recession alarm. Instead, most are pointing to several special factors for why the weak GDP report should be viewed as an aberration. Lost in the hubbub are the continued healthy labor market performance, a potentially worrisome acceleration in inflation over the past six months and the prospect of further increases in the interest rate target of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in 2017.

Data Send Mixed Signals

Forecasters have been confronted with a witches’ brew of economic data over the past several months. Some of these data have been extremely favorable. Examples pertain to solid job gains, record-high stock prices, a falling unemployment rate, and surveys of households, businesses and homebuilders that reveal an increasingly optimistic outlook for the U.S. economy.

However, other data depict an economy struggling to keep its head above water. First and foremost, an unexpected slowing in the pace of auto sales has been especially concerning—a development that has spurred automotive manufacturers to trim production, which has helped to slow the pace of manufacturing activity. Also pointing to slow growth have been a pullback in expenditures by federal and state governments and a rise in geopolitical tensions, which has elevated economic uncertainty and financial market volatility.

This tension in the data has roiled the forecasting community. Still, as evident by the steady downgrading of first-quarter real GDP forecasts before the official release on April 28, most forecasters were placing more weight on such things as auto sales than on rising levels of consumer confidence. This turned out to be a good choice.

The advance estimate for the first quarter’s GDP, published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), was appreciably slower than what the Blue Chip Consensus expected at the beginning of the year (2.2 percent). Importantly, growth of real personal consumption expenditures slowed in the first quarter to a near standstill (0.3 percent at an annual rate)—a marked contrast with previous quarters.

Some economists blame the first-quarter GDP weakness on special, temporary factors. These include the warmer-than-usual winter, which lowered consumers’ utility expenditures; delayed tax refunds because of new IRS rules; and an inventory correction, which sliced nearly 1 percent from real GDP growth.

Still, others blame the weak first-quarter growth on a quirk in the BEA’s seasonal adjustment procedure that may have artificially lowered first-quarter growth—a pattern evident over the past several years. If residual seasonality explains a goodly part of the first-quarter weakness, then the recent pattern suggests that the weak first quarter will be followed up by much faster real GDP growth in the final three quarters of the year. And indeed, that is what the forecast consensus expects: real GDP growth averaging about 2.5 percent over the final three quarters of the year, continued solid job gains and an additional slight drop in the unemployment rate.

Such encouraging news was not absent from the Q1 report. For example, there was healthy growth in real business fixed investment, residential fixed investment and exports.

The Trend in Inflation

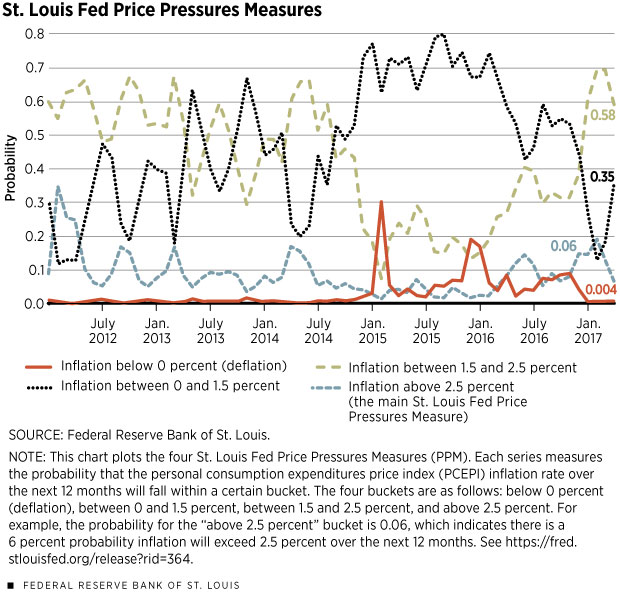

The FOMC’s preferred price index (the personal consumption expenditures price index, or PCEPI) rose at a brisk 2.4 percent annual rate in the first quarter. This was the largest increase in nearly six years and brought the current four-quarter percent change to 2 percent, which is equal to the FOMC’s inflation target. By contrast, the better-known consumer price index increased at a 3 percent annual rate for the second consecutive quarter. At this point, both forecasters and financial market participants see low probability of much higher inflation (exceeding 3 percent) over the next year. (See chart.)

As is often the case, the direction of crude oil prices could have a significant bearing on the future direction of inflation. U.S. and OPEC crude oil production (supply) is forecast to increase through the end of 2018, according to the latest forecasts from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. These production forecasts are conditioned to some extent on a continued improvement in global economic growth, which increases the demand for oil. But if the projected increase in supply falls short of demand—say, because global economic growth turns out to be stronger than expected—then oil prices will tack higher.

Kevin L. Kliesen is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Brian Levine, a research associate at the Bank, provided research assistance. See http://research.stlouisfed.org/econ/kliesen for more on Kliesen’s work.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us