National Overview: Growth Is Resilient in the Midst of Uncertainty

A rise in volatility and economic uncertainty swept through U.S. and global financial markets in late August and early September. Although pinpointing the primary source of this turmoil is difficult, many analysts have pointed to concerns about growth in China after its surprise devaluation of its currency (the yuan), about an overvaluation of stock prices and about the possibility of an interest-rate hike by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) at its September meeting. But in the midst of these developments, the U.S. economy has continued to expand at a moderate pace, job gains have been robust and the unemployment rate has continued to fall.

Second-Quarter Rebound

Growth of the U.S. economy over the first half of the year was stronger than initial estimates suggested. After increasing in the first quarter at a rather tepid 0.6 percent rate, real gross domestic product (GDP) increased at a brisk 3.7 percent annual rate in the second quarter, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reported in late August. The second-quarter rebound reflected a healthy acceleration in real consumer outlays, a significant pickup in the pace of capital expenditures by businesses, continued strong growth of real residential fixed investment, and a noticeable upswing in expenditures by state and local governments. The U.S. economy, it seemed, had regained its mojo.

Strains in Global Markets

On Aug. 11, the Bank of China announced a policy change that effectively caused its currency to depreciate by about 3 percent over the following two days. This action took many people by surprise. Then, on Aug. 24, the Shanghai stock market index plunged by more than 9 percent. Many global financial market participants, policymakers and economists began to worry that China was slowing more than most forecasters had suggested. In response, demand-sensitive commodity prices—like those for crude oil—fell sharply, adding to the volatility. In the span of five trading days in late August, the Dow Jones industrial average declined by more than 1,800 points, or a little less than 11 percent, and the St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index rose to its highest point in more than 3½ years.

But in the midst of this turmoil, the regular flow of data indicated that the U.S. economy was likely to continue to advance at a moderate pace in the third quarter—somewhere around 2.5 percent. First, consumer spending, spurred by surging auto sales, was brisk. Second, labor market conditions remained vibrant. Average monthly job gains thus far in 2015 are nearly 200,000; the unemployment rate in September was 5.1 percent, well below the median rate since 1960 of 5.8 percent. Third, housing activity strengthened further in July. Home prices were continuing to increase, and homebuilder confidence was at levels last seen in 2005. Finally, because of improving finances, construction spending by state and local governments was on the upswing and hiring by them was advancing at its strongest pace since 2007.

As always, there are crosscurrents in the data that portend emerging risks. Reflecting the sharp appreciation of the dollar since July 2011 and weak growth among key trading partners (Canada, Europe, Asia and South America), exports of U.S. goods tumbled by nearly 9 percent from October 2014 to February 2015. The fall in exports worsened the rapid buildup in business inventories that began over the second half of 2014. In response, manufacturers slowed the pace of activity to better bring inventories into alignment with sales.

The FOMC Stands Pat

In the midst of these crosscurrents, the FOMC voted Sept. 17 to maintain its 0 to 0.25 percent target range for the federal funds rate. The committee noted that recent developments in global financial markets and the appreciation of the dollar could both slow the pace of U.S. economic activity and put additional downward pressure on consumer prices, which in August 2015 were up only 0.3 percent over the previous 12 months. But much of the recent slowing in headline inflation stems from the more than 50 percent plunge in crude oil prices over the past year—a development that also appeared to reduce long-term inflation expectations. But if, as expected, oil prices stabilize (or even rise modestly), then inflation will begin to rise—perhaps to about 2 percent by about the middle of next year.

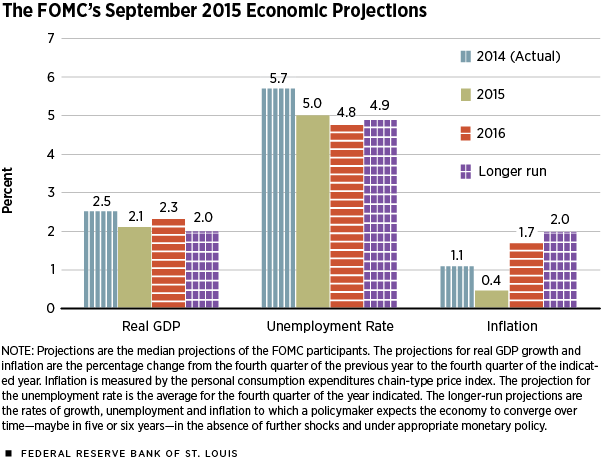

As seen in the chart, the FOMC also remains confident that the dip in inflation is temporary—though most participants expect inflation to be less than 2 percent next year. They also expect that the pace of real GDP growth will remain moderate and that the unemployment rate will continue to edge lower in 2016.

Lowell R. Ricketts, also of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, provided research assistance.

Views expressed in Regional Economist are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

For the latest insights from our economists and other St. Louis Fed experts, visit On the Economy and subscribe.

Email Us